Until very recently, shochu has had the reputation for attracting a target audience of elderly or homeless people, due to its cheap price and high alcoholic content (around 25%). But back in 2003, shochu not only caught up with the more sophisticated sake (rice wine), but actually outsold its grown up cousin for the first time.

Until very recently, shochu has had the reputation for attracting a target audience of elderly or homeless people, due to its cheap price and high alcoholic content (around 25%). But back in 2003, shochu not only caught up with the more sophisticated sake (rice wine), but actually outsold its grown up cousin for the first time.

The sales increase could well be down to a shift in image; shochu is now a drink more identified with young, professional females as well as students of both genders, who often drink it with a sour fruit syrup. It is also converting people with claims of health benefits, first and foremost of which is that shochu has less calories than most other alcoholic drinks, and the few calories it does have are usually burned off by body heat. Many also claim that shochu can prevent ailments such as thrombosis, diabetes and even heart attacks. The real boost to shochu’s image, however, came courtesy of Shigechiyo Izumi, who died in 1986 at the (reputed) age of 120! Izumi drank brown sugar shochu on a daily basis and claimed it kept him in good spirits; doctors may have disagreed, but Izumi stated: “Without shochu there would be no pleasure in life. I would rather die than give up drinking.”

The exact origin of shochu is unknown, but it can be traced back to the 16th century, as the missionary Francis Xavier visited the Kagoshima prefecture in 1549 and commented that there was a “Japanese drink araki,” (alcoholic drinks of a similar strength to shochu used to be known as araki) which was drunk by the local inhabitants, “but I have not seen a single drunkard. That is because, once inebriated, they immediately lie down and go to sleep.” This still happens today, but the average salary men now fall asleep on each other’s shoulders during their commute home.

Although it has a long history, shochu became extremely popular in the 19th century during the Meiji period, when Great Britain brought over machinery that was capable of repeated distillation, a process that allowed the base ingredients to be fermented several times, meaning more alcohol could be made from fewer resources. This came at a perfect time, as there was both a population boom and rice shortage, so cheap and readily available alcohol was obviously popular.

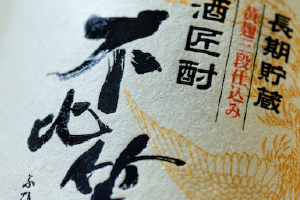

Shochu is a very hard alcoholic drink to define, but it is generally made to be a strong and relatively cheap drink which can be drunk in a number of ways: neat, with ice, hot, mixed with tea, or more commonly nowadays, mixed with a fruit-flavored syrup to make a cheap cocktail or “sour”. Shochu is defined not only by its strength, but also by its prominent taste and smell, which may well be down to it not being filtered, unlike drinks such as tequila, whiskey or vodka, which are often filtered through a pious substance like charcoal to acquire a smoother and more palatable taste. This pungency was once the main reason many people were put off the drink, but now its distinctive aroma is one of it’s draws.

Shochu is a very hard alcoholic drink to define, but it is generally made to be a strong and relatively cheap drink which can be drunk in a number of ways: neat, with ice, hot, mixed with tea, or more commonly nowadays, mixed with a fruit-flavored syrup to make a cheap cocktail or “sour”. Shochu is defined not only by its strength, but also by its prominent taste and smell, which may well be down to it not being filtered, unlike drinks such as tequila, whiskey or vodka, which are often filtered through a pious substance like charcoal to acquire a smoother and more palatable taste. This pungency was once the main reason many people were put off the drink, but now its distinctive aroma is one of it’s draws.

Although it is most commonly made from potatoes or rice, there are many different variations made from dozens of different ingredients. This article will take you through the best and strangest variants of this amazing drink, which you can buy from most liquor stores or supermarkets.

The first and cheapest drink is Kikicho Unkai, which costs a mere 960yen. It is made from soba, the same buckwheat flour that is used to make soba-noodles. It does not taste too dissimilar from shucho made from regular wheat, but it has a much more earthy smell and aste, whilst being milder and easier for some to drink. It is not exactly a refined drink, but if you are looking for something cheap yet drinkable, this would be a very good candidate.

Next up is Makiba no Yume, a shochu made from milk (yes, milk!) It has an odd taste and does not really lend itself too well to mixers such as tea or sweet syrups, but drinking it straight or with ice is acceptable, as is heating it up for a nice winter drink. This is definitely a desired taste, so invite some friends over to share the bottle, just in case you don’t like it. It is cheap enough to make it a venture worth taking, though, as even if it sits on your window ledge, it makes for a cool ornament and conversation starter for any guests that might pop round. You should be able to find a bottle in most convenience stores or supermarkets for around 1000 yen.

If you wish to stay in as healthy shape as Shigechiyo Izumi, one of the most popular brown sugar shochus available is Rento, made in the Kagoshima prefecture. Unlike other alcoholic drinks made from sugar (such as rum), brown sugar shochu has a mild and not particularly sweet taste. The drink was not always recognized as a shochu, as it was not originally labeled as shucho in the 1949 Alcohol Tax Law, but when the Amami islands (the main producers of this particular drink) returned to Japanese sovereignty in 1953, the drink went through an identity change to lower tax and appease the public. Nowadays, brown sugar shochu is one of the most popular and cheap versions available. A bottle of Rento should cost around 1130 yen.

It would be difficult to have any sort of Japanese culinary list without mentioning somethingflavored with green tea, which is where Gyokuro Shochu pops up. It is made with Gyokuro tea, a special type of tea that is grown in partial shade, unlike normal tea which is produced in full exposure to sunlight. By taking the plant out of the sun for a full two weeks before it is harvested, the caffeine and amino acid levels in the tea increases, whilst something called catechin (the ingredient which gives green tea its distinctive and bitter taste) goes down. This tea is normally sold at a premium price, but Gyokuro Shochu remains on the right side of affordable at only 1450 yen.

It would be difficult to have any sort of Japanese culinary list without mentioning somethingflavored with green tea, which is where Gyokuro Shochu pops up. It is made with Gyokuro tea, a special type of tea that is grown in partial shade, unlike normal tea which is produced in full exposure to sunlight. By taking the plant out of the sun for a full two weeks before it is harvested, the caffeine and amino acid levels in the tea increases, whilst something called catechin (the ingredient which gives green tea its distinctive and bitter taste) goes down. This tea is normally sold at a premium price, but Gyokuro Shochu remains on the right side of affordable at only 1450 yen.

Iichiko is a company that have been advertising their shochu as a premium drink since 1983. Their television commercials usually consist of a Billy Banban song, a picturesque setting and a lone bottle of shochu – a lesson in minimalism that shows this drink can sell itself. Since then, they have been claiming that the large wheat they use to produce their drinks makes for a unique taste. Although there are cheaper options available, their Iichiko Special is a wonderful drink that shouldn’t break the bank, costing 2180 yen in most stores.

During winter there is an abundance of chestnuts which the Japanese use to make a range of delicacies, many of them sweet and most of them delicious. There are also a number of shochu that make the most of this seasonal treat, but Dabada Hiburi is exceptional. The brewery is situated in the Kochi prefecture and still uses very traditional methods to produce its drinks. They sell a number of products, many of them affordable, but if you wish to try their chestnut shochu, you will need to pay around 2880 yen per bottle.

There is obviously an extensive list of shochu that I have not had a chance to mention, so apologies to any fans who feel that they have been shortchanged, but no matter if you are a regular drinker or a curious new comer, any of these drinks should be suitable. We only ask that you enjoy them sensibly and in moderation.

By Adam Miller

From WINING & DINING in TOKYO #38

Recent Comments