The yakuza are a source of fascination, but remain hidden in a world shrouded with secrecy that most Japanese people are completely naïve about. Author Shoko Tendo writes explicitly about her life as a yakuza boss’ daughter in her novel Yakuza Moon, and lifts the lid on this subterranean society.

The yakuza are a source of fascination, but remain hidden in a world shrouded with secrecy that most Japanese people are completely naïve about. Author Shoko Tendo writes explicitly about her life as a yakuza boss’ daughter in her novel Yakuza Moon, and lifts the lid on this subterranean society.

Having sold over 100, 000 copies, and translated into 12 different languages, it is unique in that it is written from a female perspective, as the daughter of a gangland boss, and later the wife of a mobster. It is a fast, heady, hundred miles an hour ride through a violence-ridden world that lies beneath the surface of Japan’s veneer of complacent calm.

Laudable in that it avoids the overly romanticized yakuza chivalry cliché, or the apologetic, overly moralistic confessional style diary–both of which are over represented in Japanese literature–Tendo Shoko’s “Yakuza Moon” is far from either.

Uncomfortably graphic, the account is a seething, drug, violence, and sex addled testimony to life growing up in the yakuza world, with a no holds barred candor, written in a rather matter of fact style.

It is hard to know what to expect when meeting Tendo for her interview, and showing up to the hotel lobby for the interview, the tiny authoress is outfitted in a hip flannelette shirt exuding a pleasant, if not, radiant demeanor.

“Thank you so much for today’s interview,” she says bowing her head. She adds beaming, “Its great that people have an interest in my experiences.”

In fact, the more she talks, the harder it is to imagine her as the protagonist of this stygian tale, and subject to such adversities such as rape, rampant drug abuse, and vicious beatings that have necessitated her face to be completely reconstructed.

“With yakuza films, there is always a hero and a filmic ending,” she says in reference to most accounts of the Japanese underworld.“The reality is not like that at all, it is gritty, and harsh. So I really wrote about what goes on beyond, how much my mother agonized, and had so many arduous ordeals over my father.

“In the films, the yakuza wife is really on the ball. Incredibly head strong, and won’t budge, with an energy that says, ‘Even without my husband, I can manage.’ The truth is different. My mother was scolded, she hid in the toilet and cried. It was really like that.”

The book starts with her fairly pleasant, if not unusual upbringing as the daughter of an affluent, powerful yakuza boss on the outskirts of Osaka, which quickly crumbles as her father’s businesses collapse and he falls into debt.

Tendo in her early teens joins a yanki gang, and thereafter, her anecdotes are fraught with drug-addled violence, stints at a reform school, fights, and eventually a speed and sex fueled affair with her family friend, a lecherous loan shark, whom her father was indebted to.

It is only after she is bashed to near death in a love hotel and injected with lethal doses of amphetamines, that she finds the will to overcome her drug addiction, but this is hardly the last of her tribulations.

It is only after she is bashed to near death in a love hotel and injected with lethal doses of amphetamines, that she finds the will to overcome her drug addiction, but this is hardly the last of her tribulations.

After failed suicide attempts, a dissolved marriage with a gangster, life as a hostess, and the eventual death of her parents, she finds that she is truly alone, at which point she decides to follow a childhood dream to write a book, having found solace in pages when she was a bullied student with no friends.

“I really thought hard about what I wanted to do, and I realized I wanted to write. I decided to write a book about the first half of my life. It is probably really melodramatic, but in that midst, I think there are a lot of parts that someone can read and go, ‘Oh me too, me too,’ and can empathize with what I have to say.

“For example, the readers may have experienced violence from men, they can’t recover from the death of their parents, they have experienced depression, they have failed suicide attempts, they were once a delinquent, they have gotten hooked to drugs… I think that everyone has something close to these things that they are worried about. I started writing this thinking, if they can interpret the book according to their feelings, and they find solace in that, it would be wonderful.”

The book is indeed heart wrenching, and ultimately it is hard not to admire this woman for her strength in adversity, and quite simply, her miraculous ability to remain alive. Unsurprisingly, the novel has reached out to many people. Some of the fans are, surprisingly, members of the yakuza themselves.

“After the penal laws changed, and I could get letters from jail, the most frequent opinion that was across the board was, ‘I’m really impressed that you managed to write it so candidly.’ I have also received letters from people from the ages of 12 to 80.”

Of these pen pals, the most memorable for Tendo was a junior high school girl who reconciled her relationship with her mother and stopped prostituting herself after exchanging letters with her. “Yakuza Moon” is one of the few books that delves into the reality of the newer bubble era generation of yakuza gangsters which is entirely removed from the heroic Showa era representations of this feudal underworld.

Tendo admits that back in those days, these kinds of characters existed–the pre-war bakuto and tekiya (gamblers and peddlers) derived mobsters are indeed said to have lived by strict moral ideals that were influenced by a samurai code of ethics, and frowned upon prostitution, drugs and loan sharking.

It was this notion of the chivalrous mobsters that has remained in the national psyche fuelled by novels such as retired yakuza member Joji Abe’s best selling novel about the ganster’s life “Hei no naka no Korinai Men Men” (“men behind walls who don’t learn lessons”), followed by “The Lonely Hitman, Kizu,” and even “Gokudo no Onnatachi” about gang women, which frightened but enamored Japan with its stoic traditionalist ideologies that seemed to be disappearing from modern Japan.

Given her disparaging account of her yakuza experiences, I ask her tentatively if there are any benefits to growing up in a gangland household, and her unassuming, yet sweet air shifts to one of pride, and says defensively, “Yes! There are a lot of favorable things about growing up in a yakuza family! For one, their manners are impeccable. And when I’m talking to someone, I am really good at reading what they are thinking, or from their eyes tell what kind of person they are. From their facial expressions, I can see if they are trying to fool me, so in that way it is very advantageous. It makes me very calm. “The yakuza are extremely strict with manners, and I can understand more than other normal girls parts of the male psyche, although sometimes that can be to my detriment too. I also understand the hierarchy of relationships and when to refrain from saying something. For example, I really know when not to say something… I’m grateful for that.”

Given her disparaging account of her yakuza experiences, I ask her tentatively if there are any benefits to growing up in a gangland household, and her unassuming, yet sweet air shifts to one of pride, and says defensively, “Yes! There are a lot of favorable things about growing up in a yakuza family! For one, their manners are impeccable. And when I’m talking to someone, I am really good at reading what they are thinking, or from their eyes tell what kind of person they are. From their facial expressions, I can see if they are trying to fool me, so in that way it is very advantageous. It makes me very calm. “The yakuza are extremely strict with manners, and I can understand more than other normal girls parts of the male psyche, although sometimes that can be to my detriment too. I also understand the hierarchy of relationships and when to refrain from saying something. For example, I really know when not to say something… I’m grateful for that.”

Asides from being about the Japanese underworld, “Yakuza Moon” is more so a story about a woman dealing with her adversities, and although Tendo laments her clunky writing skills, the novel is likeable for its honesty, in all its unglamorous glory.

“Writing about the sexual aspects of the book openly was extremely difficult,” Tendo admits. “People who read this really want to know about these things. They really want to know about things that are unpleasant. There are books like this, but up until now, the books I’ve read, when the woman writes about sex, and drugs, that area is fuzzy. It will be ambiguous, like, ‘We would do something, and then when I woke up, he was there.’

“That’s not honest, is it?! People really want to know about what happens in these instances. I felt that if I didn’t write about these things it would be purely self serving, so I really suffered when I was writing it.”

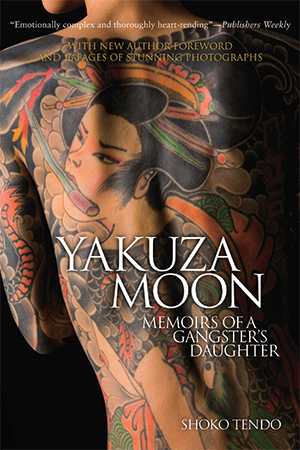

One of the things that empowered Tendo, during her lifetime was to get a full body irezumi (Japanese traditional tattoo) when she was 21. For her, this signified an end to her dependence on violent men, and gave her the strength to move on.

The dust jacket with her heavily adorned body is certainly one of the most immediately striking things about the book, and certainly is one of the strongest visual associations one has with the yakuza.

“It’s not really that any thing good comes about because you have tattoos,” insists Tendo. In fact, she says being heavily tattooed has limited her chances of being employed. She adds, “It’s more that I am satisfied. Since I was a child, I was brought up around people that all had tattoos, so to not have them is strange. It is so obvious that you would have them, that if there are no illustrations on the skin, it is a really weird feeling. I can’t really seem to relax.”

She recalls the ordeal of getting the tattoo, and the pain that can result in a fever, however, not wanting to get laughed at by her yakuza friends for being weak, she got her entire tattoo done in a week.

“Strangely, even though I’m a girl, it seems like I have directly inherited my father’s blood,” she says of her sporadic bouts of machismo, “…in that way I have the perspective of my father, as opposed to a regular female.”

Reading the book, it is evident that much of the book is about reconciling her relationship with her father, and his influence on her life is seemingly paramount.

And having become a parent herself in 2005, despite the violence of her upbringing, she doesn’t see the wider society raised on the bubble era mentality doing a much better job.

“The kids of today seem extremely spoiled, from my perspective. They are parent and child, but that line is blurred and its more like friends… It’s not wrong, it might be friendly and great, but for me, I don’t ever want to have that kind of relationship with my children…

“Parents aren’t here forever. Don’t ever think that they will live for such a long time, and live life like that, then you can think independently what you need out of life. I was always conscious of my parent’s mortality. Most kids don’t think of such morbid things, but I always thought that. And I would always cry at night, but it worked out for the best as in reality, I did lose my parents in my 20s.”

Now life for Tendo is much happier, and seemingly idyllic. She spends time with her child and her sister, carves Japanese hanko stamps, draws illustrations, and has finished her second book, which will be released in December, which is decidedly a more lighthearted account of being a single mother in Japan.

Although, ultimately, this new book is a story about discrimination. “It is incredibly different if you are single mother from the beginning, or a single mother because you got divorced. From before, there is an unpleasant expression, ‘a bastard,’ which kind of has scandalous connotations. This persists.” However, despite the joy being a mother and being able to write gives her, the main thing she is grateful for is the fact that she has survived.

“I had a failed suicide at 25 years old. My heart stopped three times. And I still didn’t die. After that, my physical condition deteriorated, and I still didn’t die, so I realized that to live my life until it is time to go is a really wonderful thing.”

She adds as a final comment, demonstrative that while her tale is one of pain and endurance, being the daughter of a yakuza boss is more than skin deep. “I think it’s because my parents really did their best in bringing me up.”

Story by Manami Okazaki

From J SELECT Magazine, September 2009

Recent Comments