The words are from a haiku by Matsuo Basho, evoking the multi-layered complexity of Nara, a city the Japanese have great affection for. In the sixth century Japan dipped its toes into the great flood of Chinese culture, when Buddhism first appeared; by the eighth century, it was swimming in it. Shinto, with its view of death as pollution, held that when an emperor died, the capital should be rebuilt elsewhere. Perhaps it was the ascent of Buddhism that convinced the powers that be to establish Nara as a permanent capital in 710, though it only remained one for 70 years. Casting off Chinese and Indian prototypes, the city became the crucible of a nativist Japanese style in art and culture.

The words are from a haiku by Matsuo Basho, evoking the multi-layered complexity of Nara, a city the Japanese have great affection for. In the sixth century Japan dipped its toes into the great flood of Chinese culture, when Buddhism first appeared; by the eighth century, it was swimming in it. Shinto, with its view of death as pollution, held that when an emperor died, the capital should be rebuilt elsewhere. Perhaps it was the ascent of Buddhism that convinced the powers that be to establish Nara as a permanent capital in 710, though it only remained one for 70 years. Casting off Chinese and Indian prototypes, the city became the crucible of a nativist Japanese style in art and culture.

Though Nara has been called the “Buddhist Rome,” the scale there is quite different from Kyoto, and many people find the city, as I did, rather soothing. Unlike Kyoto, which has thriving industries and other sources of revenue, Nara lives largely on tourism and the generosity of pilgrims. It’s a combination that doesn’t work for everyone. Writing in her 1960 Travelogue, The Flowery Sword, Ethel Manning described making her way up the slope from the railway station, along Sanjo-dori, the “twentieth century at its most vulgar worst, full of souvenir shops, neon-lit bars, raucous radio.”

Although there is much more to peripheral Nara, the central sights can be seen within a day or two. Most of the features of interest are contained within the park, the religious core of ancient Nara. This includes the deer park, where the sacred animals pig out on rice crackers bought from vendors by tourists. The deer were once regarded as sacred, divine messengers, a belief that didn’t save many of them from disappearing during the lean and hungry days of WWII.

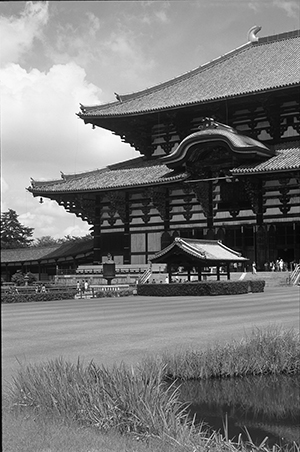

The joints of Todai-ji temple, the largest wooden structure in the world are, literally, frozen in time, hardened into positions that only a very mighty earthquake could dismantle. The first casting of the Great Buddha at Todai-ji temple did not go well. After eight attempts, the final bronze casting, made in 749, was a success. Emperor Shomu may have been prompted to erect the Buddha as an antidote to a great smallpox epidemic that had been raging at the time. The colossus stands in its barn-like building, gathering dust until a team of monks scale the form during their annual cleaning of the statue.

The poet Shiki, uncomfortable in his agnosticism, much admired these old Nara buildings. Perhaps it was the endless multiplication of religious images though, that led him to write:

Autumn wind –

For me there are no gods

No Buddhas

Carp and turtles, almost deities themselves, reside in Sarusawa Pond, on a cherry tree lined road below the magnificent Five-Storey Pagoda. It’s a pleasant place to sit and have a drink or bite, while contemplating the pagoda on the escarpment above.

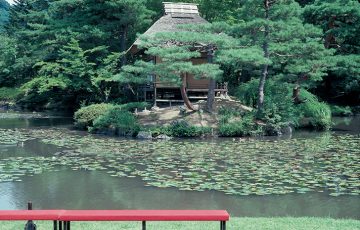

The pond garden of Kyu-daijo-in is less known. Though it was redesigned by the landscape master Zen-ami in the Muromachi period, today’s garden is little more than a tracery of the original. Isui-en, an early Edo era garden, is more promising. A little north of the splendid Nara National Museum, the garden has two ponds, one with millstones used as stepping-stones to a small island. Surrounded with miniature trees and carefully trimmed bushes, white lotuses bloom at the edges of the pond. Rising in green tiers above the garden, visitors can glimpse a segment of the south gate of Todai-ji and Mt. Takamado behind. A smaller nearby garden, Yoshikie-en, is an even quieter spot for the kind of contemplation that Japanese gardens lend themselves to.

I liked the ethos at Nigatsu-do, a very old temple on Nara’s eastern boundary that has a broad wooden terrace affording superb views of the city. No one was charging an entrance fee here, and a restroom had been set aside for visitors where they could help themselves to cold water and buckwheat tea. The temple represented the little met spirit of generosity and hospitality towards travelers and pilgrims at the heart of Buddhism. None of these ancient buildings might be here if it wasn’t for Dr. Langdon Warner, who is credited, though no longer remembered, for having persuaded the United States not to drop an atom bomb on Nara.

These great, slow cities turn with the seasons. Unless you are lucky enough to live in ancient places like this, the visitor will only ever experience partial views, excluded by time and season. If you could be here on January 15th, for example, you could see priests firing grass on Mount Wakakusa to the east of the city. In autumn there is a procession of priests in ceremonial robes and children decorated with flowers, around Sarusawa Pond. Young women in kimonos join the proceedings in memory of a spurned imperial concubine. Unloved, she hung her kimono on a weeping willow tree, before entering the pond, and death, stark naked.

Following the ancient paths of the city inevitably takes you to the little visited ruins of Heijo Palace in the northwest of the city, near old keyhole-shaped burial mounds. The site was also a compound of sorts, its walls acting as a cordon sanitaire dividing royalty from the commoners they knew virtually nothing about, the privileged from those who tilled the paddies and toiled in the fields. I walked the area, but a bicycle would have been better as the area consists of 120-hectares of completely exposed flatland, without a drink vending machine in sight. Foundation stones and border lines surface from beneath a large expanse of grassland, hinting at the scale but not the form of the Imperial Domicile and government offices that sat here some 1300 years ago.

Raised structures with ascending steps, similar to the bases of Mayan pyramids, turn out to be the foundations of grand gates leading to state compounds used for ceremonies and banquets. Other remains are the foundations of a Ministry of Personal Affairs, the Imperial Audience Hall, the Office of Imperial Foodstuffs and Office of Rice Wines and Vinegar. There are good views from the top of these modest elevations, taking in the palace grounds, Yamato Plain to the south and a western range of mountains.

The stones of a well located inside the imperial residence are well preserved, and, along with stone drainage ditches and ponds, help to conjure up the past. Excavations of such spots began on the site in 1958. The artifacts unearthed since then have shed considerable light on the social and living conditions of the aristocracy of the time and their retainers. The models, maps, dioramas and individual items displayed at the Nara Palace Site Museum there are a good introduction to the area.

Aware that not every visitor is able to recompose the palace in their mind’s eye, excavation work on the site has been followed up with reconstructions of the original buildings. One of the first replicas to go up was Suzaku Gate, a two-storey edifice that you glimpse from the train bound for Kintetsu Nara station. The line cuts through the southern portion of the historical site. The gate was the largest of twelve entrances to the palace, and judging from the current one, probably the most impressive. Willows have been replanted nearby. Segments of palace walls have been rebuilt, and clipped evergreens, tubular in shape, indicate where the original pillars of buildings once stood. To the northwest, the former Imperial Hall is currently being reconstructed and should be open for viewing in 2010.

Arguably the most impressive section of the grounds is the To-in Teien (East Palace Garden). The Nara period garden that was excavated, appears to be more of a faithful recomposition than reconstruction. Added to the ground plan of pond, pebble beaches, winding stream, and original stone clusters, are reconceived walls and pavilions. The site was uncovered in 1967, but the finished work took a full 30 years to complete. The site gives us a notion of a lifestyle it was previously only possible to have visualized through reading the poems and literature of the day, such as the Kaifuso and Man’yoshu anthologies.

In Nara I began to wonder if Japan, as it is often described, is really a wood culture? It seemed to me, looking at many of the ancient foundations and founding designs of buildings and monuments, that if you go back far enough, it is the stones and rocks that remain. Perishable wood, unless someone has maintained the building or site down the ages, is likely to have rotted away a long time ago. Certainly, stones were supremely important to Japan’s early ancestors. In pre-animistic times, large rocks were used as markers delineating the occupation of property or land. At some point the original function of rocks was set aside for more mystic purposes. In a world without temples, shrines, or religious reliquaries, the natural world provided landscapes and natural features conducive to worship.

In Nara I began to wonder if Japan, as it is often described, is really a wood culture? It seemed to me, looking at many of the ancient foundations and founding designs of buildings and monuments, that if you go back far enough, it is the stones and rocks that remain. Perishable wood, unless someone has maintained the building or site down the ages, is likely to have rotted away a long time ago. Certainly, stones were supremely important to Japan’s early ancestors. In pre-animistic times, large rocks were used as markers delineating the occupation of property or land. At some point the original function of rocks was set aside for more mystic purposes. In a world without temples, shrines, or religious reliquaries, the natural world provided landscapes and natural features conducive to worship.

Today’s Nara, naturally enough, is an inevitable mix of stone, wood and cement, culture and commerce. Perhaps this is the way of the modern world, and we shouldn’t complain too bitterly. Even Ethel Manning, deploring the tackiness of the souvenir shops along Sanjo-dori, still managed to find beauty and rarity among the shabby products of the day, noting “here and there a small antique shop showing pieces of faded lacquer-ware, a tarnished Buddha image, an old and exquisite painting on silk, quietly, unostentatiously, almost anonymously.” It is a fitting description of travel in Japan, where selective vision always works best.

TRAVEL INFORMATION

Nara has two train stations: the JR Nara Station and the private Kintetsu Nara Station. Both connect to local cities like Kyoto and Osaka. Nara has plenty of information offices. The most convenient is the Nara City Tourist Information Center on Sanjo-dori. The stylish and expensive Nara Hotel (tel: 0742 26-3300, web: www.narahotel.co.jp/English/index.html) occupies a Meiji era building and has fine private gardens. Ryokan Matsumae, a friendly, English speaking place, has comfortable Japanese style rooms, and they won’t break the bank. Nara is well served by buses, but its relatively small scale makes walking and cycling ideal. Some ryokans offer bicycle rentals. Otherwise, try Eki Rent-a-Cycle outside the JR Station. The nearest bus stop for the Nara palace Site is Nijo-oji Minami 4-chome, just opposite the Suzaku Gate.

Nara has two train stations: the JR Nara Station and the private Kintetsu Nara Station. Both connect to local cities like Kyoto and Osaka. Nara has plenty of information offices. The most convenient is the Nara City Tourist Information Center on Sanjo-dori. The stylish and expensive Nara Hotel (tel: 0742 26-3300, web: www.narahotel.co.jp/English/index.html) occupies a Meiji era building and has fine private gardens. Ryokan Matsumae, a friendly, English speaking place, has comfortable Japanese style rooms, and they won’t break the bank. Nara is well served by buses, but its relatively small scale makes walking and cycling ideal. Some ryokans offer bicycle rentals. Otherwise, try Eki Rent-a-Cycle outside the JR Station. The nearest bus stop for the Nara palace Site is Nijo-oji Minami 4-chome, just opposite the Suzaku Gate.

Story & photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, November 2008

Recent Comments