The single line train from Hashimoto to Koya-san is worth the entire trip in itself. The track cuts and winds into the side of mountains, creating an observation shelf down into steep, densely forested valleys. Glimpses onto the tiled rooftops of villages, narrow, fine tooth-combed fields fitted between forested slopes and unhurried stops at wooden station buildings along the way, speak of a different, quieter age.

The single line train from Hashimoto to Koya-san is worth the entire trip in itself. The track cuts and winds into the side of mountains, creating an observation shelf down into steep, densely forested valleys. Glimpses onto the tiled rooftops of villages, narrow, fine tooth-combed fields fitted between forested slopes and unhurried stops at wooden station buildings along the way, speak of a different, quieter age.

Some 120 temples, monasteries, sanctuaries and schools, and a half million tombs no less, are dug into the mesa. Unlike some great Buddhist centers (one thinks sadly of Lhasa), Koya-san has neither languished for want of the faithful, or been violated.

Even during efforts to purge Buddhism during the Meiji era, the mountain held its own. Its elevation here in the Wakayama mountains may have helped. And the fact that such illustrious figures as Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi are interred here, would also have deterred the religious desecration associated with those years.

Koya-san is the premier site of Shingon Mikkyo, an esoteric sect of Buddhism, founded in 816 by the priest Kukai, also known by his posthumous name Kobo Daishi.

Given the established facts of Kobo Daishi’s life, his reputation hardly needed burnishing with the kind of exaggerated accounts, legends and miracles that sprang up after his death. A truly remarkable man for his time, the future saint, a gifted scholar and calligrapher who traveled extensively in China, is credited with founding Japan’s first public school and inventing the hiragana syllabary.

It is not difficult to picture Kobo Daishi wandering through these misty mountains all those centuries ago. His robes would doubtless have been saturated with damp and filth after months trudging through these hills, co-existing with snakes, monkeys, wild boar and leeches.

Today’s henro (pilgrim) is an altogether different creature, apparel crisply laundered and ironed, conveyed by bus, all effort circumvented by modern amenities. Whether or not they are as fiercely devoted to their faith is another question.

Hundreds of priests, monks and novices minister to the needs of the temples and the generous devotees of Kobo Daishi who have somehow managed to make this complex look opulent but feel like a place of privation.

Hundreds of priests, monks and novices minister to the needs of the temples and the generous devotees of Kobo Daishi who have somehow managed to make this complex look opulent but feel like a place of privation.

You wonder at the effects on the clergy of dietary restrictions and the rejection, however temporary, of the world.

One of Japanese writer Nakagami Kenji’s short stories, The Immortal, is set in these strange mountains. In response to severe depravation and abstinence, the main character, a priest who has been wandering in the mountains longer than is good for him, suddenly finds himself searching for a bamboo grove, wanting to eat something fire had passed through and wanting to embrace a woman whose body had warmth.” In the story, he is able to satisfy both desires, but at a high cost.

We can suppose that the moral rectitude of the contemporary priesthood is of a higher order, though the Koya-san section of one recent guidebook warns darkly that one or two women traveling alone have complained of some mildly unmonkish behavior.”

Koya-san is not just a temple town. Where there are temples in Asia, there are markets. It has its shops, a junior high school, a baseball ground, clusters of souvenir stores, restaurants, cafes, parking lots, even a pachinko parlor, whose rows of seated devotees appear to be experiencing a state not too far from the Zen concept of mushin, or no-mindedness.”

Koya-san is a great deal to take in on a single day trip, but many visitors try to include the Reihokan (Treasure House) into their busy itineraries. Ideally, its huge collection of artworks, should be left to the end, its best known treasures the Reclining Image of Sakyamuni Buddha on His Last Day and the sensual Eight Guardian Deities making a fitting coda to a day spent on the mystic side of these mountains.

Several well-known gardens add interest to the town. What the Banryutei garden at Kongobu-ji Temple lacks in subtlety, it makes up for in symbolism and scale. The largest stone garden in Japan, the rocks are said to represent a pair of dragons emerging through a sea of clouds. The dragons serve to guard Kobo Daishi’s mausoleum.

Carried there upon his death, in the very same meditation position that he remains now, the saint is believed to be alive today sunk in contemplation, but aiding all living beings. Two meals are served him daily.

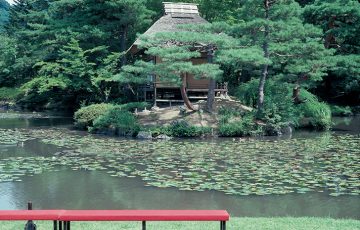

Another garden of interest can be found at Fukuchi-in, a temple and inn. The landscape here is said to symbolize the fusion of Buddhism and Shinto, a principal that has been practiced on Koya-san since it’s founding.

The garden was created by Mirei Shigemori in the early 1970s. Arguably, the foremost figure in the renaissance of the dry landscape garden, Shigemori’s work represented a dynamic innovation, the like of which the Japanese garden world had not seen. And like all radical shifts, this one deeply divided the garden establishment. It is a testament to the originality of Shigemori’s work that it still does.

Most controversial, perhaps, was his use of concrete, something vigorously opposed by purists. Shigemori wrote that a garden should have a timeless modernity; what is singularly modern in our time has no real value.” Only time will tell whether Shigemori’s gardens will live up to his own standards for longevity.

Most controversial, perhaps, was his use of concrete, something vigorously opposed by purists. Shigemori wrote that a garden should have a timeless modernity; what is singularly modern in our time has no real value.” Only time will tell whether Shigemori’s gardens will live up to his own standards for longevity.

In another garden of sorts, the forest-cemetery known as Okunoin, the mystic core of Koya-san, the smell of incense, of Buddhism itself, is pervasive. The faith holds that one’s karma can be improved by the burning of incense. Other religious notions compare the life of humans to the evanescent smoke from sticks of incense.

Traditionally, incense was used to summon spirits but also to repel malign forces that held sway over diseases. The spirits of men who had sold bad incense for profit, deformed into incense-eating goblins, were believed to haunt the burning sticks, their only source of nourishment.

Lafcadio Hearn claimed the smell had the power to evoke the past, that many of his own experiences of traveling in Japan remain associated in my own memory with that fragrance: vast silent shadowed avenues leading to weird old shrines; mossed flights of worn steps ascending to temples that moulder above the clouds.” It could very well be a description of Koya-san.

Old-growth forest is a rarity in Japan, as elsewhere. Walking here beneath the towering cypresses and broad-leafed trees of the great cemetery is a privileged experience.Forests have invaded family plots, creating shady, humid patches of moss, fern and lichen. The trunks of cedar trees have also been requisitioned by the graveyard, serving as sheltered hollows for Jizo-san statues, mortuary tablets and flattened stone Buddhas. This mutual infiltration has created that strange oxymoron: a living cemetery.

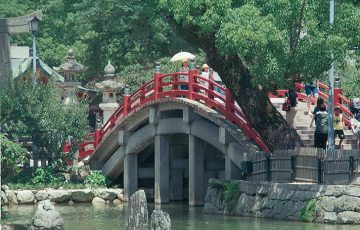

The cobbled, gnarled paths that snake their way through the forest end at Lantern Hall. Several thousand lanterns burn here; one, astonishingly, has been kept alight since 1016, another from 1088, the early years of the Norman Conquest in Britain.

On the altars of the temples here, as elsewhere in Koya-san, powdered incense is poured over hot coals, creating a unique aroma. There are no weeds on Koya-san. The moss and leafy, vine-like overhangs above tombs may look like the result of neglect, but this is a deliberately tolerated effect, reflecting an ascetic found, for example, in the Japanese tea garden.

Koya-san’s tombs lend themselves to all climatic moods, looking equally impressive in rain (melancholy), snow (purity), filtered sunlight (paradisic) or soaked in damp mists (eerie).

Exiting the gigantic forest and its diminishing effect on the human figure, you regain a little stature. While there is no question of the timeless, plangent beauty of Koya-san, it’s a relief to leave the mortuary town for the airy cable car, to get the incense out of your lungs to rejoin the living.

Travel Information

Koya-san lies some 50 kilometers south of Osaka. Osaka’s Namba Station is one starting point. Take the Nankai train to Hashimoto, changing to Koya-san. Tickets include the cable car. Buses depart from the cable-car terminal every 20 minutes for the 10-minute ride into town. There is a tourist information office inside the cable terminal, with maps and information in English. Some 50 or so shukubo (temple lodgings) offer tradition facilities and first rate shojin ryori (vegetarian, temple food). The friendly Rengejo-in (tel: 0736-56-2233) dates from 1190 and has bags of atmosphere. For more information on lodgings, contact the Koya-san Tourist Association (tel: 0736-56-2616). An important ceremony and service takes place on the 21st day of the third lunar month (mid-April). Kobo Daishi’s birthday (June 15) is another cause for festivities. Thousands of lanterns illuminate the forest during the August Obon festival of the dead.

Story & photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, April 2007

Recent Comments