How do you spot the sole artist in a room? Besides the telltale clues like a sketchpad and beret (well, I’m kidding about the beret), he’ll likely be chuckling to himself about some joke that’s lost on left-brainers. Or perhaps he’ll be pointing out the bad design that prevents your spoon from scooping out the final elusive bites of dessert from an elegant but unpragmatic receptacle.

How do you spot the sole artist in a room? Besides the telltale clues like a sketchpad and beret (well, I’m kidding about the beret), he’ll likely be chuckling to himself about some joke that’s lost on left-brainers. Or perhaps he’ll be pointing out the bad design that prevents your spoon from scooping out the final elusive bites of dessert from an elegant but unpragmatic receptacle.

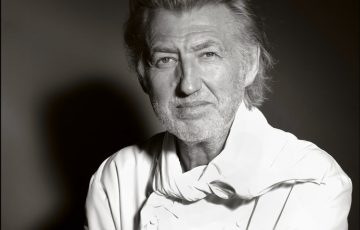

This is the world according to David Stanley Hewett, a Tokyo-based painter and ceramicist. Hewett grew up on the East Coast of the US with a bohemian mother who painted and lent the garage out to a studio-less potter, so his exposure to artistic expression began at an early age. He started painting as a preschooler and picked up pottery a few years later, so art has always had an impact on his life.

Clearly, having decades of practice under his belt has improved his skill set, but some of Hewett’s abilities exist on a more intrinsic level. Ask him to describe someone he’s met recently, and he will most likely draw a blank, but mention the color of the curtains or the scent in the air at the time and he’s there. He explains, “It’s all smells or colors or images. I don’t think you can learn that, so it must be genetic from my mom.” This also causes Hewett to see the world a little differently, prompting him to find beauty in often overlooked details, like worn gold door fittings at a shrine or wood on an old barn.

Hewett’s exposure to Japan also began at an early age. In junior high, he started practicing karate, and continued studying Japanese culture and language through college. During university, he spent a year in Hokkaido doing “precious little studying” and began his entrée into the Japanese art world soon after by studying with Tokyo-based avant-garde sculptor and ceramicist Sachiko Kawamura.

In his early days as the proverbial starving artist, Hewett began exploring Japanese materials, dabbling with washi and Japanese ink in addition to the ceramics he studied with Kawamura. Since he was a young, unknown foreigner, it seemed nearly impossible to line up a show, but he persevered. Hewett recalls, “I went to, I don’t know, 30 galleries with my slides, and they all just said ‘No, no, no, no.’ But I don’t think it was as much the quality of my work as it was they didn’t think a foreigner would stick around.” Finally, Libest Gallery in Kichijoji agreed to take a chance on him, giving him what turned out to be his first big break. Not only did the gallery sell 17 of the 19 pieces they showed, but an interior designer who saw the exhibit decided to enter Hewett’s work in a competition for the Imperial Hotel. As the winner, Hewett was commissioned to do an astounding 108 paintings for the Imperial. Not a bad gig for someone who’d been teaching English by night to support his artistic ambitions.

After the initial fanfare, Hewett took a detour, doing what he jokes “any good artist should do,” spending time in the Marine Corps, then running an import business and publishing Takara, a Japanese-language magazine in the Boston Area. He returned to Japan in 2000, and when we met for our interview he’d just celebrated his 10-year anniversary here.

The past decade has brought an impressive array of accomplishments, from solo shows at Bunkamura and Takashimaya to commissions for top-tier hotels and businesses. Yet there’s more to the story. It wouldn’t be much of a stretch to say that Hewett has in fact been leading a double life, since he’s held down a full-time job as an investment banker the whole time. Though banking and beaux arts may not have much in common, Hewett’s ability to navigate both worlds has had a clear role in his success. He acknowledges, “I’m lucky because I enjoy doing business as well as being creative. I actually enjoy the business part of the art world, whereas a lot of artists don’t.”

Having a keen business sense has certainly helped Hewett to become commercially successful, but his talent is what continues to draw in the collectors, gallerists, and interior designers. He describes his style as graphic and easily lending itself to patterns. This seems to put potential buyers at ease since they know what to expect when commissioning Hewett’s work.

The pattern-like nature of his work has also helped open doors Hewett didn’t even know existed. While his paintings were on display in Takashimaya in 2008, unbeknownst to the artist, the gallery manager submitted his work to an obi design competition, and Hewett won. He recounts, laughing, “He called me up one day and said, ‘You won the competition,’ and I said, ‘What competition?!’” What began as a blind foray into textiles proved so successful (Hewett’s obi was the top seller at Takashimaya that summer), that he was subsequently invited to design a line of men’s and women’s yukata for the store. Takashimaya was unequivocally pleased with the collaboration – they’ve asked him to do a tour of shows in several major cities in 2011 and 2012.

For the past four years, Hewett has been deeply entrenched in his “Bushido” series, which “a lot of people describe as design rather than fine art or avant-garde art, and I agree with that.” Paintings from this series feature strong lines of gold leaf against dark brown or black backgrounds with hints of red.

The inspiration for the series began with someone very close to Hewett – his wife. She comes from a strict Shinto family, influencing him to read up on Shinto and the related tenets of Bushido. While often translated as “the code of the samurai,” Hewett considers the concept to be “more of a code of life.” Drawing upon Shinto and his military and martial arts background, Hewett began to reflect on how he could express these intersecting ideas in painting. According to his description, hard lines and dark colors represent the military and martial arts, while red is reminiscent of blood, action, and passion. The concept for the gold began during a visit to Sumiyoshi Shrine in Osaka, where Hewett admired the worn gold fittings on the doors. However, the idea really began to take hold when he visited an exhibit of byobu (or folding screens) at the Suntory Museum. “The gold leaf had kind of rubbed away a little bit and it was extremely beautiful to feel the age through that. And so I tried to recreate that as a sense of history of the longevity of the idea of Bushido. These ideals are not something that one picks up as a fad; they’re part of the DNA of Japan.”

After four years, does Hewett feel ready to leave the world of behind? Not yet, apparently. “I’ve got a few hundred more of these in me, I think,” he responds, explaining that it’ll be time to move on “when I paint what I’m happy with.” For now, though, he enjoys the challenge of working within a largely circumscribed world, saying, “I like the simplicity of the palette I have to choose from and how many different ways you can make that canvas speak with very few materials.” He also finds that tweaking with ideas like scale helps him to stay inspired, and recently his canvases have begun to take on larger than life proportions.

Despite his clear commercial success and occasional propensity to get lost in the unexpected beauty in the details of daily life like a remarkable restaurant counter, Hewett gives the impression of being someone who is firmly grounded in the real world. He attributes some of this centeredness to his work with various charities, explaining, “It’s just a good anchoring for your soul to remember these things and to pay attention to them.”

Despite his clear commercial success and occasional propensity to get lost in the unexpected beauty in the details of daily life like a remarkable restaurant counter, Hewett gives the impression of being someone who is firmly grounded in the real world. He attributes some of this centeredness to his work with various charities, explaining, “It’s just a good anchoring for your soul to remember these things and to pay attention to them.”

He began participating in Refugees International Japan’s “Art of Dining” fundraiser in 2008. In this event’s earlier incarnations, ambassadors’ wives would decorate tables in luxe hotels with place settings, ceramics, and flowers. Over the years, however, artists and designers have become increasingly involved in the event, so Hewett has taken it upon himself to remind attendees about RIJ’s mission to help displaced people around the world. Last year, he created 1,200 plastic poker chips with images of starving children on them. He set the chips up on the table, so “from a distance it looked very Art Deco… and as you got closer, you got the images and you went, ‘Whoa! What’s going on here? This feels wrong!’” Though it may have been uncomfortable to see images of starving children in such an atmosphere of excess, Hewett says many attendees approached him with positive feedback. As an artist, though, he welcomes both positive and negative reactions to his work. The worst thing, he says, is to simply leave viewers uninspired. “Even if they don’t like it and you get them to think about something, then maybe that’s success, too.”

Given that this is his view of success, I’m surprised to hear Hewett say his early years in Tokyo – before his work had been shown publicly – were some of his best. He believes that the lack of outside input led him to an unfettered exploration of his artistic identity. “I was painting exactly what I wanted to paint, so in that sense it was creatively a very free time,” he explains. He goes on to say that “I hope I’m still very creative, but I think to some degree, artists get self-conscious as they get older, and then as you get even older probably less self-conscious again.”

Given that this is his view of success, I’m surprised to hear Hewett say his early years in Tokyo – before his work had been shown publicly – were some of his best. He believes that the lack of outside input led him to an unfettered exploration of his artistic identity. “I was painting exactly what I wanted to paint, so in that sense it was creatively a very free time,” he explains. He goes on to say that “I hope I’m still very creative, but I think to some degree, artists get self-conscious as they get older, and then as you get even older probably less self-conscious again.”

To aspiring artists, Hewett admits that in Japan it’s tough, especially to get that first show, but foreigners should take heart that it’s more about what you produce than where you come from. That said, he’s observed some amusing differences between the Japanese and foreign buyers at his larger shows. “The Japanese folks who don’t know me already and are just walking by look at my résumé, are impressed, and then buy something. The foreigners that come in look around, like a piece of art and then buy it. And then afterwards they go, ‘Oh, who is this guy?’” No matter how they approach it, though, there’s no doubt that all sorts of audiences find Hewett’s work appealing.

In the next few years Hewett will keep busy preparing for his touring shows at Takashimaya, and while nothing is definite, he’s negotiating with a New York-based designer about an East-meets-West clothing collaboration. He’s discovered a new creative outlet with textiles and hopes to explore this further. He also has aspirations to organize a show in New York or London. Until then, though, he’ll be the guy in the boardroom or hotel lobby with the sketchpad (no beret), finding inspiration and amusement in unlikely places.

Story by Melissa Feineman

From J SELECT Magazine, April 2010

Recent Comments