blocky concrete buildings reach outwards in an organised jumble of unbroken monochrome until it reaches another neighborhood, another station. It is Saturday, almost noon, and commuters come and go through the streets of the typical shopping district behind the station. A couple of greengrocers compete for attention, plastic baskets of oranges and apples displayed to attract the eye. A small butcher’s shop is just opening, partially blocked from view by the line of people forming outside the ramen shop opposite.

blocky concrete buildings reach outwards in an organised jumble of unbroken monochrome until it reaches another neighborhood, another station. It is Saturday, almost noon, and commuters come and go through the streets of the typical shopping district behind the station. A couple of greengrocers compete for attention, plastic baskets of oranges and apples displayed to attract the eye. A small butcher’s shop is just opening, partially blocked from view by the line of people forming outside the ramen shop opposite.

This could easily be the closing scene from Juzo Itami’s ‘noodle western,’ the movie Tampopo. It’s not, however. It’s reality. This is Ivan Ramen, on an ordinary weekend.

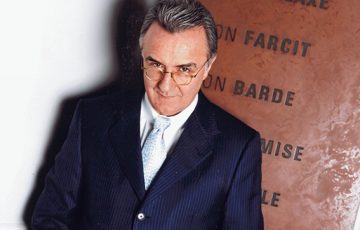

Ivan Orkin, the man behind Ivan Ramen, is confident, fast-talking, affable, blunt, and manages to give the impression that he’s eaten a lot of bagels in his time – in short, a typical New Yorker. In the eighteen months since Orkin opened his shop in Minami Karasuyama, Ivan Ramen has become something of a phenomenon: a mixture of keen business sense, excellent food, and a decent location, (which he refers to as ‘his formula’), has brought media attention and plenty of customers. Sitting at the narrow counter in his restaurant before opening time, he talks:

“I had an idea of what I wanted. I knew that being an American tackling ramen was a great story, but I also knew that an American tackling ramen could… I never thought I would do this well. I’m pretty surprised and very happy. I never thought it would last, I thought if I succeeded at all it would last a short time and then I would go back to normal. Like I said, I knew that tackling ramen in Tokyo had the chance to be big news and very successful, but I also knew that scrutiny would be much stronger so I knew that my food had to be really good, or I would just fail immediately. I’d have maybe a month or two of fame, people would taste the food, and the verdict would be, ‘Nice try, for a foreigner, but itís not really ramen. It was fun to see the white guy back there, but we’re not going back again…’ And you know, I guess that’s fair.”

The verdict, however, has been excellent. Though Orkin’s training, and noodles, are far from typical: itís apparent that Orkin plays very much by his own rules.

“I didn’t do an apprenticeship here. I’m 45 years old now, and I did my apprenticeship in New York at some pretty tough French kitchens and got beat around quite a bit, so I wasn’t really interested in working two years somewhere. I figured ‘I can figure it out.’ I knew I had to come up with the right food. But I’m a chef, and a chef’s job is to make food. If you don’t know how to make something you research it, and then you make it. Most of us work for other people, and they tell us what you’re supposed to make. If they say, ‘we need a Greek buffet,’ you don’t say to the boss, ‘I don’t know how to cook Greek food,’ you go and you buy a book on Greek food, and read about it, and figure out how to make it. I’m a professional. I decided I wanted to do ramen, so I figured out how to make it. I won’t say it was easy, it took a lot of hard work and a lot of practice, but I was a little ahead of the game because I’d been eating ramen for 25 years.

“I have a very good food memory, and I have a very clear image of what good food is and what good ramen is, and, more importantly, the type of ramen that I would like to eat. I see flavor when I cook, so I have an image of the flavor that I want to create. Itís less that I have an image of one dish that I had eaten somewhere as I have an image of a thousand dishes that I’ve eaten over six years and somehow I synthesise together the flavor that I’m imagining, and of course it’s my flavour, because no one else is in my mind, so it ends up being uniquely mine. Sometimes people express such surprise, they say ‘I’ve never had anything like this before!’ and I say, ‘Neither have I! I just made it. I made it a week ago, for the first time ever, so of course you’ve never had anything like this. No one’s ever made it before.’he funny thing is, that that’s what cooks do, we make food.

“I have a very good food memory, and I have a very clear image of what good food is and what good ramen is, and, more importantly, the type of ramen that I would like to eat. I see flavor when I cook, so I have an image of the flavor that I want to create. Itís less that I have an image of one dish that I had eaten somewhere as I have an image of a thousand dishes that I’ve eaten over six years and somehow I synthesise together the flavor that I’m imagining, and of course it’s my flavour, because no one else is in my mind, so it ends up being uniquely mine. Sometimes people express such surprise, they say ‘I’ve never had anything like this before!’ and I say, ‘Neither have I! I just made it. I made it a week ago, for the first time ever, so of course you’ve never had anything like this. No one’s ever made it before.’he funny thing is, that that’s what cooks do, we make food.

“Good food should be balanced, and flavorful, and memorable, and satisfying, and that’s good food. And it doesn’t matter whether it’s a burger, or a donut, or a foie gras terrine with a perfect apricot jam on top. People ask me all the time, you know, ‘You’ve worked in all these famous restaurants, how can you feel good about yourself serving noodles?’ Well, I’ve had some pretty shitty French meals, and I felt really bad after eating them. And sometimes you can be on the street corner in New York and get one of those pretzels, and if it’s good? Man, you feel so great. Wow, you remember it all day long.

“One of the reasons I chose ramen was that I thought it was one of the only areas of Japanese cuisine that I could do whatever I wanted. If I did washoku or tempura or udon or sushi or any of those things, there’s basically a rule book that you’ve got to stick to. And if you go too far off, your legitimacy goes out the window.

And so ramen was the only sort of maverick cuisine available, and I thought that it would give me an opportunity. Like I said, when I opened, I really played it straight. I served shio ramen and shoyu ramen and really outstandingly good, well made noodles. A very well thought out bowl of noodles that any Japanese person could look at and just go ‘Wow, this is Japanese ramen. This is fabulous.’

“I actually didn’t think of having a ramen shop until maybe March of 2006. I mean, I had sort of thought of it, you know, I do love ramen. I love Japanese culture, I love speaking Japanese, my family is Japanese. And I love cooking, and I love food. So in 2003 I had the chance to come back to Japan with my wife and the kids, which everyone thought was crazy. I knew that I was really pushing the envelope on this, but I’m sort of that way. When I decide to do something I just do it. So, I moved back to Japan, with no plan. My wife had a great job, and I didn’t have to work, so I took care of the kids. I taught cooking to Japanese housewives, and I had no idea what I wanted to do. After three years of sitting at home, surfing the web all day long, going to Isetan and window shopping, and hanging out at Tower Books on the 7th floor, I just wasn’t happy. My wife said, ‘Maybe it’s time you go back to the restaurant business. It’ll fit your hyper personality, and it might be a lot of fun.’ So we thought, what type of food? You know, the only thing I fantasized about in New York was eating a good bowl of ramen, because there wasn’t any.”

Orkin seems made for fame, so much so that it’s hard to tell where the image stops and the real man begins. This doesn’t seem to bother him at all. “I grew up in New York, not Brooklyn,” he laughs. “I’m not altruistic, of course I want people to come here. But I have no interest in becoming a geinojin (celebrity), it’s not what I want to be, I don’t want to be a movie star and I don’t want to be one of those famous gaijin who are laughing and hobnobbing on all of those variety shows. I have been on a lot of shows, but all my shows are about me as a person who makes food, and I have no problem being on TV every single day of the week as long as itís about me making food. My family is off-limits.

“I think I’ve been on TV six times in November, I’m on a lot, and I’m in a lot of magazines. My book came out today (“Ivan’s Ramen” www.littlemore.co.jp). Of course I want to succeed, and I want to make more money and all of that, but I really feel that the more different places that I’m able to tell my story, the more interesting mix of clientele I get.”

If media attention is simply a way of feeding more people, cooking, for Orkin, is a way of creating relationships. “My goal is to connect with as many customers as I can every day, and take that opportunity to pick a customer who is having a bad day and make it better, or take a person who is having a good day and make it a great day. I like feeding people. I’m a Jewish grandmother type of cook, I watch people eat. It makes me happy when they look satisfied.”

Despite an infectious enthusiasm for good food, and a hearty dislike of commercial fast food, Ivan Ramen’s next step is a soon-to-be released instant ramen. Orkin seems unconcerned about the apparent contradiction with his “slow food” based philosophy. “I’m a businessman as well. Like I said, I grew up in New York, not Brooklyn. Being open one year and being asked to sell an instant ramen is unheard of. It’s usually the five years before you’re asked to make something like that, so I consider it quite an achievement. Like I said, I don’t eat things like that. I ate the first one they made for me to taste, and I thought it tasted terrible. So I said, ‘This is just awful, you know, it has a horrible aftertaste, the noodles are too yellow, with no flavour.’ So we worked on it, and actually, for an instant ramen, it’s not bad.”

Despite an infectious enthusiasm for good food, and a hearty dislike of commercial fast food, Ivan Ramen’s next step is a soon-to-be released instant ramen. Orkin seems unconcerned about the apparent contradiction with his “slow food” based philosophy. “I’m a businessman as well. Like I said, I grew up in New York, not Brooklyn. Being open one year and being asked to sell an instant ramen is unheard of. It’s usually the five years before you’re asked to make something like that, so I consider it quite an achievement. Like I said, I don’t eat things like that. I ate the first one they made for me to taste, and I thought it tasted terrible. So I said, ‘This is just awful, you know, it has a horrible aftertaste, the noodles are too yellow, with no flavour.’ So we worked on it, and actually, for an instant ramen, it’s not bad.”

This kind of dedication to detail is typical of Orkin, though it would have been simple enough put his mark of approval on a standard product, he seems intent to create the very best instant ramen possible, one that is chemical-free and surprisingly includes whole wheat flour.

“People seem to enjoy eating instant ramen, I mean itís very popular, people really like it. So if I have a chance to make an instant ramen, why not make one of the better instant ramens on the market? I worked really hard and I hope people think itís one of the better ones theyíve tried. It’s good for me, it’s great advertising, and, you know, it’s fun.”

Fun, more than anything, is at the heart of Orkin’s passion for ramen. He passes me a bowl of steaming noodles over the counter. The hot broth makes my glasses fog over. “I think that ramen is happy food. I think it’s comfort food. I think slurping up noodles and splattering grease all around your blouse and the table around you and your eyeglasses takes a certain need to relax and have some fun.” And so, I pick up my chopsticks, and dig in, soon too engrossed in perfectly chewy noodles and a sharp, clean soup to worry at all about the splatters.

By Skye Hohmann

From WINING & DINING in TOKYO #35

Recent Comments