You know you are in a sub-tropical, summer climate the moment you see the vibrant flora and early blooms of Japan’s volcanic gardens. On the islands of Shikoku, Kyushu, and Okinawa, one is immediately struck by the luxuriance of flowers, mandarin and citrus fruits, and the city esplanades lined with cycads and phoenix palms.

You know you are in a sub-tropical, summer climate the moment you see the vibrant flora and early blooms of Japan’s volcanic gardens. On the islands of Shikoku, Kyushu, and Okinawa, one is immediately struck by the luxuriance of flowers, mandarin and citrus fruits, and the city esplanades lined with cycads and phoenix palms.

The first inklings of spring in the sub-tropical parts of Japan are felt with the early blossoming of the wisteria, rainy season irises and hydrangea, the vibrant blue and purple Japanese bellflower, water-lilies, and the fragrant gardenia, its scent similar to the South-East Asian plumeria.

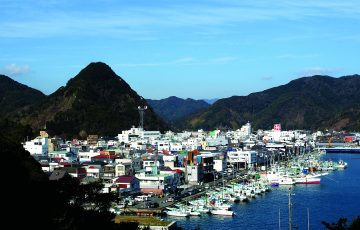

In Kagoshima vaporous clouds billow testily from Sakurajima’s sliced head, its wind-born ash settling like black snow into drifts outside shop fronts and along garden walls. Still further south, in Chiran, a small town of tea plantations, old wooden samurai villas that sit among choppy, volcanic hills and shallow valleys in the heart of the Satsuma Peninsula, there are gardens that seem on thrive on the severity of the region’s climate and geography. In Okinawa you are in the sub-tropics proper, among islands where palm trees, bougainvillea, red and yellow hibiscus, plumeria, banyan and bamboo orchids are commonplace.

Traveling through the south in the 1960s, the English poet James Kirkup, wrote “Kyushu, seahorse on a capering keel… The neat, tremendous garden of Japan.” Despite the industrialization in the north and the oil refineries of Kagoshima, the island is still a green Camelot.

In Beppu, geothermal heat rises from the earth through lush green surfaces that create landscapes of fantastic configurations, steam curling above the friable crust into scalding pools, or gushing with terrifying force from the outside pipes and faucets of its hot spring inns. The most celebrated are its Jigoku (Boiling Hells), pools of mineral-colored water and bubbling mud.

Sub-tropical gardens luxuriate around these boiling hells. Surprisingly, the gardens at the edge of these life-withering pits appear to be nourished rather than withered by contact with pools seething with radon, sulphur, ferrous and magnesium. Lusty palms grow in botanical profusion, and giant lily pads at Umi Jigoku, an ocean colored pool set in a bowl of hills, and its bonsai pines, flourish in the steamy air.

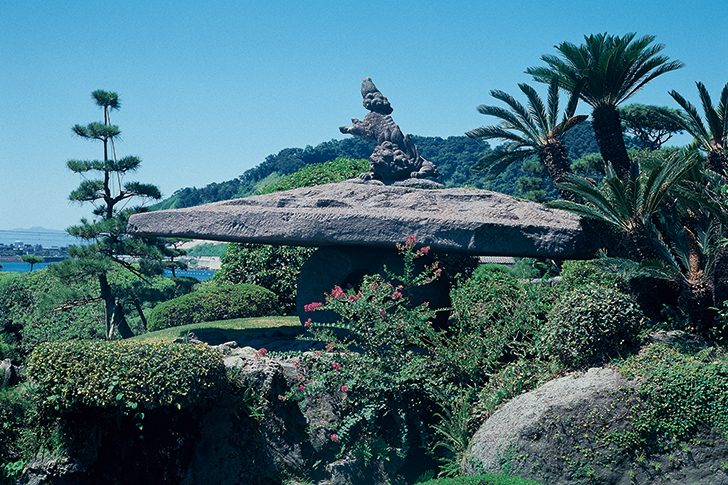

Further south, the volcanic soil of Sakurajima produces summer mandarins, the world’s largest turnip, and quantities of loquats. The subterranean heat of the volcano stunts growth in one place, stimulates it in another, as with the banyan trees, a species normally associated with Southeast Asia, that luxuriate along the island’s western sea walls. Kagoshima’s sultry climate is apparent at the Iso-teien garden, one of the city’s main attractions, where semi-tropical plants grow alongside plum and bamboo groves.

A nearby gazebo, another hint of the south in an island that borders an ocean that seems bluer and more typhoon-prone than elsewhere, was a gift from Okinawa.

Decorated with colorful Chinese tiles, the Bogakuro as it is known, a rather dark, stained wood pavilion was presented by the King of the Ryukyu Islands (Okinawa) during the time of the 19th Lord Mitsuhisa.

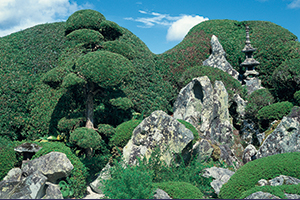

Chiran is a small town of tea plantations, old wooden samurai villas, volcanic hills and shallow valleys at the heart of the Satsuma Peninsula. Its gardens and green, sub-tropical lanes do well in the heat and sunshine of southern Kyushu. Chiran is best known for its miniature, Edo period gardens, design landscapes that cleverly match the natural surroundings of their own village.

Chiran is a small town of tea plantations, old wooden samurai villas, volcanic hills and shallow valleys at the heart of the Satsuma Peninsula. Its gardens and green, sub-tropical lanes do well in the heat and sunshine of southern Kyushu. Chiran is best known for its miniature, Edo period gardens, design landscapes that cleverly match the natural surroundings of their own village.

Each garden at Chiran is named after the head of the family who lived in the house. Rocks are carefully angled, plants and miniature trees beautifully arranged, old lanterns and Buddhist stones add depth.

The contrast between the different shades of green, the color of the azaleas, the hedge, and the emerald hills on the horizon is a very effective technique. The top of the hedges are clipped like topiary, into angles so that they match the outline of the hills. Some of the gardens display borders of bonsai in the Okinawan manner.

Although relatively Spartan in their plantings, southern latitudes are keenly sensed in Japan’s karesansui, or dry landscape gardens. In stone gardens there is a strong sense, even in relatively young gardens, of antiquity and decay. This is perceived as a maturing of the garden, an enhancement rather than a spoiling or erosion. This mood is especially sensed during the humid months. The beauties of erosion are seen in mottled and streaked rocks, stone lanterns, water-basins covered in moss and lichen, and in the ancient patinas of clay and mud walls. The Japanese genius for garden design, is expressed here as elsewhere, in the seamless blending of art and nature through an extraordinary economy of means. Everything in its ordained place. Though executed in the formal manner, these southern gardens seem less solemn when viewed under radiant sunlight.

Blue seas, coral, and luxuriant flora are the hallmark of the Okinawan islands. In the land of passion fruit, mango, custard apple, pineapple, papaya, dragon fruit and banana groves, its trees are often what visitors first notice. The ghostly banyan tree is confined mostly to the village, where it’s aerial, stilt branches support a cool overhead canopy and filaments of hemp-like tendrils, knotted into ghoul heads.

Elsewhere, fukugi and Indian almond trees are common. Among the island flowers are bamboo orchids, hibiscus and plumeria. Taking root on the fringes of beaches are pineapple-like pandanus trees. Outside the margins of villages are sea-facing palms, pandanus, Indian almonds, and fukugi trees.

Elsewhere, fukugi and Indian almond trees are common. Among the island flowers are bamboo orchids, hibiscus and plumeria. Taking root on the fringes of beaches are pineapple-like pandanus trees. Outside the margins of villages are sea-facing palms, pandanus, Indian almonds, and fukugi trees.

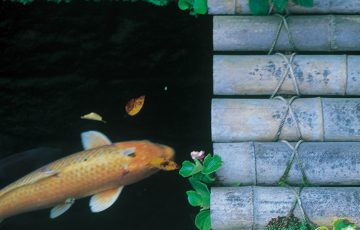

Traditional homes are surrounded by a coral wall. Some of the older gardens have a second inner wall, in the manner of Chinese screen walls intended to deflect or confuse malignant spirits from entering the house. They also serve as windbreaks and ensure privacy. The outer walls are not the geometric, rectilinear design components they are in Japanese gardens, doing service instead as shelves for flowers and plants like aspidistra and creepers, even doubling as trellises for vegetables like marrow. Trellises of bitter melon blend with papaya, banana, fig, and mango trees.

The garden’s decorative touches reflect climatic differences, but a heightened sense of color, which comes as much from the sea as the land. It may very well be that the inspiration for the first cultivated landscapes came from living on small islands surrounded by stunning displays of coral.

Linger in these marine gardens long enough, and you have a good chance of experiencing something like a genuine Okinawan trance state.

TRAVEL INFO

Oita airport serves Beppu, but there are regular train connections to Hakata on the bullet train, and local lines and buses to the hot spring. The hot spring pond-gardens are mostly located in the Kannawa district, a good place to stay. The Kannawa-en (0977 776-7811) is a magnificent old ryokan with its own lovely garden.

Kagoshima is now served by the bullet train, via Kumamoto. The Iso-teien is at its greenest in summer. Nakahara Bessou (www.nakahara-bessou.co.jp) has pleasant rooms and hot baths overlooking Chuo Park. The airport at Naha, the prefectural capital of Okinawa, is served from all major airports in Japan, though there is a comprehensive ferry network also for those with the time. The city is a good base to visit other islands.

The waterfront Loisir Hotel Naha (098 868-2222) is one of the most luxurious in the city, a butterfly-shaped swimming pool and spas add to the comfort. At the other end of the budget, the Hakusei-so (098 866-5757) has a good location near the Ichiba food market. Contact the main tourist information offices in these cities for data on more gardens and the calendar of colorful festivals held at different times of the year.

Story & photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, September 2009

Recent Comments