Customers of world-renowned French chef Joel Robuchon, dining at the Chateau Joel Robuchon at Ebisu Garden Place or any other establishments under his name in Tokyo or other countries, obviously marvel at the great cook’s success and uniqueness. Little do they know that in order to carve out a niche for himself here in the first few years, the culinary master was forced to reach new heights of ingenuity so he could be sure to have on hand ingredients essential to French cuisine. Thirty-one years ago, produce such as chives, scallions, basil or tarragon were not available anywhere in Japan, so Robuchon would hide the seasonings in one of the two suitcases he would always carry in from France. The trick? At customs, he would put the suitcase with the seasonings on top of the one containing nothing forbidden. The customs officers would always order him to open the bottom suitcase.

Customers of world-renowned French chef Joel Robuchon, dining at the Chateau Joel Robuchon at Ebisu Garden Place or any other establishments under his name in Tokyo or other countries, obviously marvel at the great cook’s success and uniqueness. Little do they know that in order to carve out a niche for himself here in the first few years, the culinary master was forced to reach new heights of ingenuity so he could be sure to have on hand ingredients essential to French cuisine. Thirty-one years ago, produce such as chives, scallions, basil or tarragon were not available anywhere in Japan, so Robuchon would hide the seasonings in one of the two suitcases he would always carry in from France. The trick? At customs, he would put the suitcase with the seasonings on top of the one containing nothing forbidden. The customs officers would always order him to open the bottom suitcase.

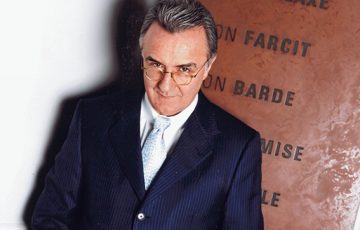

Robuchon doesn’t personally bring ingredients into the country any more because he can now find anything he needs locally. And his faithful customers also enjoy a choice of venues to taste the cooking made by him, or following his instructions. The two restaurants at Chateau Joel Robuchon, L’Atelier de Joel Robuchon in Roppongi, Cafe de Joel Robuchon at Nihonbashi’s Takashimaya and a restaurant in Nagoya make up the jewels of the chef’s Japan crown. Not to mention the other L’Atelier Joel Robuchon restaurants in Paris, London, New York, Las Vegas and Hong Kong. Yet, Robuchon is very modest about his achievements. “I’ve been lucky,” he keeps saying.

The younger of two boys and two girls, 62-year-old Joel Robuchon was born and raised by his homemaker mother and mason father in Poitiers, the main city of France’s Poitou region. Not renowned for great cuisine, the region boasts tasty dishes of snails, young goat, white beans and lots of cabbage. One of the area’s specialties is vegetable-stuffed cabbage, served hot or cold. “It’s a tasty regional cuisine, but rather spare,” Robuchon says. The chateaux of the Loire were built with Poitou stones. “So was this chateau” housing his two Ebisu restaurants, Robuchon says.

Robuchon’s family was devoutly Catholic and at age 12, he enrolled in a Catholic higher secondary school, called petit seminaire in France. As a boarder there, leaving only for Christmas and summer vacations, his only opportunity to relax was helping the nuns in the kitchen, peeling the vegetables or scrubbing the pots. The boy had found his vocation, and thankfully so. His parents divorced when he was 15 and could no longer afford to pay for his schooling. When asked what he wanted to do, the adolescent Robuchon opted for cooking. “I thought it was relaxing work and, in those days, one became a cook to be sure to eat,” he says. That was after World War II, during which time a lot of people in his parents’ generation actually did suffer from hunger.

Eat well, Robuchon certainly did, but kitchen work was far from the breeze he had cracked it up to be. An apprentice’s work started at seven in the morning, picking up the coal to heat the oven. In the afternoon, one finished washing the dishes, then mowed the lawn and after that worked on the evening service until 11pm. “Those were very long days, very different from the 35-hour working week in France today,” Robuchon says. After ending his apprenticeship at 18, Robuchon worked here and there throughout France, improving his cooking abilities while learning the cuisine of different regions such as Brittany and Vausges. Another three years passed and he married at 21, settling down in Paris. “I was the little apprentice from the Province, meeting famous people such as (artist Salvador) Dali and (opera singer Maria) Callas,” he says. “I can say I had a happy youth.”

During his formative years, Robuchon was influenced by several chefs, none of them famous, but all great professionals. He remembers Robert Auton, who could do just about anything in a kitchen, be it butchering, confectionery, pastry or cooking. “You would hand him nothing but a carrot and a turnip, and he would work up something marvelous,” he says. Or Jean Delaveyenne, a mushroom specialist, nicknamed the Sorcerer of Bougival. Or yet Charles Barriers, a Tours chef, who baked his own bread, and also made smoked salmon as well as his own foie gras, at a time when only butchers or processors made foie gras. “I learned a lot from those people,” Robuchon says.

In Paris, Robuchon progressed to the point where in 1976 he won the Best Craftsmen of France Competition. At the time, the owner of Suji Cooking School in Osaka wanted some French chefs to come and give cooking demonstrations at his school. Robuchon volunteered and was noticed by the Tokyo Hotel Okura chef, who also invited him for a demonstration. “That is how, little by little, I discovered Japan,” he says.

Introducing the Japanese to a cuisine he had no idea they would even like, Robuchon was nothing short of a pioneer. In the early Ô80s, there were no fresh truffles in Japan and having tasted only the canned variety, Japanese people were not very fond of them. Nor were they particularly partial to offal. Now, however, they can’t get enough of such delicacies.

“That’s what I like about Japanese people Ð they are open to new discoveries,” Robuchon says. “They’ll taste something and if they like it, they’ll accept it.”

He witnessed the same evolution in Japanese attitudes towards many other products. Twenty years ago, only famous brands were admired here and anything else was rejected. Although of course quality brands are still highly valued, people show a new openness towards the rest. Wine is a case in point. In the past, Japanese people would only drink the great wines of France, Italy, Germany or Austria. “Now, we see wines from Spain and other areas, even small French wines, that Japanese will drink and judge on quality,” Robuchon says.

Of course, professionalism is an important criterion, but Robuchon places respect towards products high on the scale of a good cook’s attributes. That’s because to cook something, one must always destroy a life, a fish or a beast. “Even vegetables grow,” he says.

Additionally, he believes, one must love people and love to make them happy. Robuchon’s greatest satisfaction is to see people come into his restaurant in a bad mood, looking tense, and as the meal progresses, relax and completely turn around. “When I eat somebody’s cooking, I can sense if it was made by somebody who wants to make you happy, or if it’s by obligation, to earn a living,” he says.

Robuchon practices what he preaches at his L’Atelier in Ginza, where he can focus on his customers, who sit around the kitchen. When heworks there, Robuchon watches the clients and knows what they will eat. If there is a problem, if they hesitate, he can immediately ask what is not to their liking. “Direct contact is very important,” he says. “We must really make the customers happy.”

Robuchon practices what he preaches at his L’Atelier in Ginza, where he can focus on his customers, who sit around the kitchen. When heworks there, Robuchon watches the clients and knows what they will eat. If there is a problem, if they hesitate, he can immediately ask what is not to their liking. “Direct contact is very important,” he says. “We must really make the customers happy.”

What’s more, one must continue to evolve and learn new things. “I’m 62 years old and I’m still learning a lot,” Robuchon says. He has learned a lot from Oriental cooking and an epiphany that occurred when he opened a restaurant in Macao three years ago. Westerners have always focused on the taste of food, whereas Chinese consider texture more important. It was therefore a shock for Robuchon, the consummate French chef, to see shelled shrimp run under water all day. By the end of the day, the shrimp’s taste was naturally washed out and yet, when the Chinese sauteed them in their woks, the shrimps would turn corkscrew-shaped and take on a very pleasant texture. “For me, that was a radical evolution,” Robuchon says.

Contact with Oriental cuisine also pushed Robuchon’s cuisine towards simplicity, whereas, 20 years ago, he would make a point of showing off his technical mastery. In his younger days, he would have taken a simple egg and served it hard-boiled in a broken shell, with caviar and cream whipped up several centimeters high. The Chinese, however, taught him an egg must be soft inside, but crispy outside. So he now wraps an egg in filo pastry, fries it until crisp (but not greasy), and serves it with caviar and a simple Russian-style cream. Eating that egg, we feel the soft, warm yolk inside, the crispy white, and the caviar that seasons it on top. “But what’s in there? The egg, cream and caviar,” Robuchon says. “That’s all.”

Or take a shelled prawn, wrap it in a basil leaf, role it in bique dough, fry it just a bit in oil, and that’s all there is to it. When you eat the final product, you feel the crispy exterior, the soft interior and the heightened taste of the prawn. “It sounds simple, but when you eat it, there’s something that picks you up,” Robuchon says.

Robuchon has made simplicity his trademark and hates overly sophisticated dishes. He particularly detests to be served food, and not be able to tell what he is eating. Success for him means to gather two or three elements into the making of a delicious dish. And that is why he loves the simplicity of Japanese cooking. “With Japanese cooking, you eat the truth,” he says.

His favorite Japanese dish is sushi at Jiro’s in Ginza. The owner, Jiro Ono, seasons each morsel just right, so his customers don’t need to add any more sauce. “But when you put his sushi in your mouth, it explodes,” Robuchon says. “That’s the true, true, true product speaking.

Story by Richard Smith

From J SELECT Magazine, July 2007

Recent Comments