The skies of Provence are, to be sure, a rare and unique phenomena. The light they cast down over the sycamore, cypresses, plane trees, baked roof tiles and the high, aerial villages perched on their improbable rock escarpments, provides just the right touch of chiaroscuro and drama to enhance all the best loved components of Provencal folklore. Basking at the core of this flattering Mediterranean sun is Avignon, arguably France’s most beautiful city.

The skies of Provence are, to be sure, a rare and unique phenomena. The light they cast down over the sycamore, cypresses, plane trees, baked roof tiles and the high, aerial villages perched on their improbable rock escarpments, provides just the right touch of chiaroscuro and drama to enhance all the best loved components of Provencal folklore. Basking at the core of this flattering Mediterranean sun is Avignon, arguably France’s most beautiful city.

Despite the vulgarities and intrusions of the modern age, parts of Augustus Hare’s description of the city in an early French guide book to Provence still hold true: “At Avignon the traveler will first feel himself in the south: its crenellated walls and machicolated towers rise from a country covered with olives.”

Avignon, former home to the troubadour poets and the celebrated Courts of Love, is an unequivocally romantic town, a fact not lost upon the city’s department of tourism. Avignon is also the gateway to the Vaucluse, a region of lavender fields, wild herbs, vineyards and old stone houses, the very embodiment, in fact, of postcard Provence.

Although its population barely exceeds 90,000, Avignon’s reputation as a city of art and culture proceeds it. Avignon counts as part of what might be termed Roman Provence, but its eminence as a city dates from the 14th century when Pope Clement V and his court, fleeing the political morass and excesses of Rome, established the Holy Sea there.

Avignon stood in for Rome from 1309-1377, benefiting in the process from massive papal funding, much of which went into building programs designed to glorify the city. The combination of wealth and papal tolerance turned Avignon into not only an indulgent patron of the arts, but an asylum for the political dissidents and persecuted Jews of its day.

Italians, who opposed the transfer from Rome, accused Avignon of being a city of criminals and brothel-goers. A resentful patriarch went a step further, dubbing the city “the second Babylonian captivity,” a place unfit for papal habitation.

Italians, who opposed the transfer from Rome, accused Avignon of being a city of criminals and brothel-goers. A resentful patriarch went a step further, dubbing the city “the second Babylonian captivity,” a place unfit for papal habitation.

The Palais des Papes (Palace of the Popes) is the city’s star attraction. The palace, like most of the old Gothic section of Avignon, lies within the oval-shaped walled city. The broad, echoing halls that once bore witness to shuffling cardinals, royal emissaries, and legions of bowing servants and factotums, now resound with the murmur of foreign tongues, the whirr of auto-focus cameras and the well rehearsed recitations of tour guides. Many of the spacious rooms are set aside for major exhibitions. When I was there, the palace was hosting an important and well-attended Rodin show.

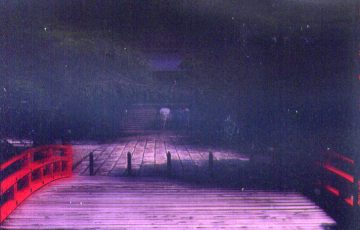

The northern ramparts of the old city, with their fortified parapets and stone gates, face the river Rhone, Provence’s most romantic waterway. Avignon’s medieval annex, Villeneuvre-les-Avignon, lies a short distance beyond the far embankment. The Pont Saint Benezet, built to link the two zones, was completed in 1185. Only four arches of the original 22 remain, and one wonders how much longer tangible pieces of the world’s most famous broken bridge will remain in tact for all to see. One is thankful its memory is at least being kept alive in a children’s nursery rhyme known to almost every Japanese person.

Villeneuve-les-Avignon, known in its day as the City of Cardinals, merits a full day’s exploration. The Pierre de Luxembourg Museum contains a fine collection of religious art and the Tour de Philippe de Bel, a 32-meter-high defensive tower, affords one of the best views across the river to Avignon’s superb walled city. The Chartreuse du Val de Benediction, one of the most important Carthusian monasteries in France, lies here. In the silence and stillness of its cloisters, chapels, stone cells and papal mausoleum, can be found some of the most sublime Gothic artisanship of the 14th century. Interestingly enough, its value as a place where visitors can collect their thoughts, has been recognized by the French Ministry of Culture, who have funded a program that invites composers, film scriptwriters and playwrights to stay and work there free of charge.

Avignon’s continued patronage of the arts is apparent each summer with the Festival d’ Avignon, an international event that attracts visitors from all over the world. A staggering 300 performances or more are staged every day, some in the most improbable locations. Like the Edinburgh Festival in Scotland, the Avignon Festival is split into two simultaneous events: the official, Ministry of Culture-subsidized festival and the so-called “Festival Off.” The artists who decide to turn up and perform free of charge in this latter alternative festival event, put on some of the most vibrant mime, dance, song, drama, poetry, story recitals, marionette performances and other spectacle de rue, to be found during Avignon’s month-long tribute to the arts.

Major accommodation and traffic problems typically accompany the festival, and anyone planning to arrive at this time would be well advised to find a room outside the city, or to wait until two or three weeks after the event when most residents of Avignon try to escape the bedlam of the high season by taking their own vacations. With the approach of autumn, the quiet inner courtyards, ringing bells, paddle wheels and cobblestone lanes of Avignon revert to something like their medieval character.

Despite the charms of Avignon and the allure of the Vaucluse, the region is not without its problems. Like many other ancient European cities, Avignon has suffered its share of defacement at the hands of city planners and developers. Serious housing shortages following the Algerian war in the 1960s saw the over hasty construction of vast, faceless dormitory suburbs and a mash of new motorways that have left deep incisions not only on Avignon, but other noble Roman towns in the region such as Nimes, Beziers and Narbonne. As subterranean catacombs and wine cellars nuzzle against underground parking lots, it may seem at times as if history is being squeezed out to make room for more cars and tour buses.

Despite the charms of Avignon and the allure of the Vaucluse, the region is not without its problems. Like many other ancient European cities, Avignon has suffered its share of defacement at the hands of city planners and developers. Serious housing shortages following the Algerian war in the 1960s saw the over hasty construction of vast, faceless dormitory suburbs and a mash of new motorways that have left deep incisions not only on Avignon, but other noble Roman towns in the region such as Nimes, Beziers and Narbonne. As subterranean catacombs and wine cellars nuzzle against underground parking lots, it may seem at times as if history is being squeezed out to make room for more cars and tour buses.

Avignon, with its rich heritage, outstanding architecture and patrimony, is not an easy city to deride as debased or commercialized, however. Its festival bears continued witness to its vitality as a major patron of the arts and the pellucid skies of Provence, a blue dome towering over the medieval ramparts of Avignon, remain as magnificent as ever.

Travel Information

Spring and early summer promise good weather, although the festival in August is a fascinating time to go if you can find accommodation. The lavender fields of the Vaucluse are also at their best then. It is possible to fly to Avignon from Paris and other major cities in France and Europe. The Aeroport d’ Avignon-Caumont is eight kilometers southeast of town. There are regular express trains from Paris’s Gare de Lyon and elsewhere. There is an excellent choice of hotels in and around Avignon. Highly recommended is the centrally located, mid-price range Hotel Danieli, at 17 Rue de la Republique. Formula 1, a chain of motels found all over France, offer the cheapest accommodation at about five kilometers from town.

Lawrence Durrell’s Caesar’s Vast Ghost: Aspects of Provence is a highly original read; Michael Jacobs’s A Guide to Provence is a well-written profile. Long before Peter Mayle Ð he of A Year in Provence Ð got there, Lady Fortescue was writing delightful accounts of living in the region, such as Perfume from Provence.

Story & photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, July 2007

Recent Comments