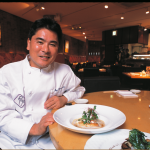

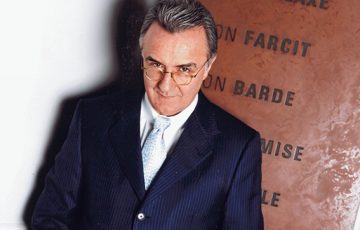

Photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto has spent much of his life inviting audiences to re-evaluate conventional notions of time and space. Jonathan Day catches up with the conceptual artist during a recent visit to Tokyo for the launch of a special retrospective exhibition held in his honor. Portraits by Androniki Christodoulou.

European and American artists have historically viewed conceptual photography with a certain amount of disdain, particularly when compared to prevalent artworks of the modern era such as post-modern paintings and sculptures.

Flying in the face of such feelings, photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto committed himself to exploring the nuances of time, space and perspectives, and subsequently rose above his contemporaries to become one of Japan’s most important living artists.

Tokyo-born Sugimoto left Japan in 1970 after receiving a diploma in economics from Rikkyo University. He backpacked through the former Soviet Union and Europe, and ended up in California, where he enrolled in the eminent Art Center College of Design, known for its conceptual orientation. At that particular time, however, Sugimoto was more interested in securing a student visa with his application than he was about studying.

“I ended up in California half by choice, half on a whim,” recalls Sugimoto. “It was an exciting place to be at that time, in the post-Beatles, hippy movement era. I wanted to see what was going on there. I wanted to check out the movement, to see exactly what it was all about for myself. I enrolled in art school because art school was the easiest to get in and get a visa. Photography had always been a hobby of mine and I’d always been fairly handy with a camera. I’ve had my own dark rooms since junior high school. I wasn’t a good student although in my time at the Art Center College of Design I learnt how to handle large format cameras (4 x 5 / 8 x 10) and I basically became professionally trained as a photographer.”

Moving to New York in 1974 was a sobering experience for Sugimoto, whose circumstances dictated that it was time for him to rejoin mainstream society. New York in the mid-1970s was at the center of the global conceptual art scene and Sugimoto had been particularly inspired by the creations and dialogue of minimalist artists such as Carl Andre and Dan Flavin. Having now been schooled in the ways and means of professional photography, Sugimoto took up a number of positions as an assistant photographer to pay his rent, none lasting more than a couple of days at a time before his customary critical remarks regarding his employers’ photographic techniques rendered him jobless. New York’s conceptual art scene, however, provided Sugimoto with a soon-to-be fertile ground upon which he could ply his unique trade – fusing concept with time-honored technique.

“It wasn’t my intention to be a photographer but I had to pay my rent,” he says. “I looked for jobs as a commercial photographer but I was a terrible assistant because I always criticized my bosses. I soon found that commercial photography was not for me, so moved more towards New York’s minimalist and conceptual art scene that was booming at the time. I found the whole contemporary art scene quite fascinating and I thought to myself, ‘why not adapt my photographic technique to the art world?’ At that time, photography was very much considered to be the art world’s second-class citizen, so the challenge for me was to raise the profile and stock of conceptual photography and make it a first-class citizen. It was a huge undertaking. Painting and sculpting at the time were very traditional and well-represented art forms, but photography was a young medium so there was a chance for me to make my mark.”

“It wasn’t my intention to be a photographer but I had to pay my rent,” he says. “I looked for jobs as a commercial photographer but I was a terrible assistant because I always criticized my bosses. I soon found that commercial photography was not for me, so moved more towards New York’s minimalist and conceptual art scene that was booming at the time. I found the whole contemporary art scene quite fascinating and I thought to myself, ‘why not adapt my photographic technique to the art world?’ At that time, photography was very much considered to be the art world’s second-class citizen, so the challenge for me was to raise the profile and stock of conceptual photography and make it a first-class citizen. It was a huge undertaking. Painting and sculpting at the time were very traditional and well-represented art forms, but photography was a young medium so there was a chance for me to make my mark.”

One of Sugimoto’s first commissions to gain recognition was his Diorama series (begun in 1976). For this series, Sugimoto photographed wax figures in their staged settings at Madame Tussaud’s in London and at Movieland in Hollywood. He also used a number of museum displays as his subject matter, including stuffed polar bears and Neanderthal families. These formative prints were an early indication of Sugimoto’s fascination with the ability of art to warp perception simply and effortlessly, posing philosophical questions to his audience about the nature and relationship between art and life.

“In the 1970s the conceptual photography genre didn’t exist in the art world so I had to find my own way to present my ideas the way I saw things,” he says. “The way I see the world through my photography is and was the most important part of what I do. One day I was looking at my Natural History Museum Diorama series and I simply closed one eye and my sense of perspective was completely lost. All of a sudden what I was looking at became so realistic. Humans with two eyes are naturally measuring the distance between themselves and the objects they are looking at, and thus things are always in perspective. But the camera has only a single eye and this creates a different photographic reality that gives people an enhanced sense of reality, even though it’s a totally different system of seeing and confirming an object.”

Although on one level Sugimoto’s art purports to be a blank canvas upon which his devoted audiences can project subjective meanings and interpretations, the artist is uncompromising when it comes to his underlying sensibilities that shape and animate his iconic prints. For Sugimoto there is always a tangible starting point, a supposition of sorts that provides the impetus for the entire project. Taking this line of reasoning further, it’s Sugimoto’s obsessive adherence to his own painstakingly high technical standards – developed and honed over the years – that carries his projects through to fruition. Sugimoto has always used a simple 19th–century view camera, which he himself describes as “nothing special” and “out of fashion.” He always works with the same formats and ratios, and he hasn’t altered his intricate method of film development over the years. He tests and mixes his own chemical formulas for developing his photographs (in a process he likens to alchemy) and the exact ingredients remain a closely guarded secret to this very day.

“I envision the scenes first and the next step from there is how to make it happen realistically,” he says. “There has to be an original idea to start with, just like science. You start with a hypothesis and you try to prove or disprove the theory. One original thought I had was perfectly minimalist, ‘what would happen if I took a picture of an entire movie.’ I guessed the movie image would end up shining and over-exposed and the light might look as though it were emitting from the screen and illuminate the theater’s interior. The first test I did was amazingly successful, considering it was all guess work, and that there were a lot of variables I couldn’t control, such as the duration of the movie – meaning the exposure length. The only things I could control were the lens and the F-stop, so I brought a very bright lens and set my F-stop to 11 and the results were great. I ended up shooting 100 theaters in Europe, the United States, Australia and Japan.”

In addition to his Theater series, Sugimoto is also well known for his arresting Seascapes. Taken in different parts of the world (but using identical formats for each), Sugimoto “paints” distinguishing atmospheres into each and every seemingly featureless print. Taken at different times of the day, under different lighting and weather conditions, the waters and horizons differ vastly from picture to picture. On close inspection one can notice differences in wave and tidal momentum while the angles, vibrancy and density of the light reflecting off the water are also unique. The Mori Art Museum describes this series as “objects for meditation and awe,” rather than screens for mere self-projection. Sugimoto himself, however, sees the series as a portal back to a time when we first became aware of the concept of “self.”

“Tracing back my oldest memories of first seeing the sea, I wanted to recreate old visions from my childhood,” he says. “These seascapes are anonymous and when I first saw the sea I realized my own existence in the world. This was a very important memory for me. It represents the collective memory of mankind – when we first found culture, written language, when we first became aware of ourselves as humans as distinct from uncivilized animals. I would describe this embryonic recognition of ‘ourselves’ as a hazy-awakening and this is underlying point of my Seascape series,” he says.

From September 17 until January 9, 2006, the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo will display a retrospective exhibition on Hiroshi Sugimoto’s entire collection. Entitled End of Time, the exhibition will feature his best-known works, including pieces that earned him the much-coveted Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography in 2001 and the Mainichi Art Prize in 1988. Audiences will also be treated to a world-first viewing of some previously unreleased work.

“I’ve been working exclusively in black and white throughout my entire career, but after many years of investigation I plan to show the world for the first time in Tokyo how well I can work with color,” he says. “Ironically, the prints for the series Colors of Shadow are the most monochromatic color prints I’ve ever made. It all started with me constructing a wall in my apartment in order to photograph it. I spent five years making this composition before I could finally shoot it. The traditional Japanese wall I built was made with precise angles of 90, 55 and 30 degrees. In the morning, when the sun rises, it throws rays of light on these three different angles. When it rains, when it’s hazy, the small changes of shadow are very delicate and naïve. I can quite happily sit and watch the shadows all day.”

The End of Time exhibition will also feature Sugimoto’s Architecture series, another of prominent importance to the contemporary conceptual art world. Iconic 20th-century landmarks such as Empire State Building by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, Le Corbusier’s Chapel de Notre Dame du Haut and the Church of Light in Osaka by Tadao Ando have been deliberately shot out of focus so as to redefine form and capture the ambience and soul of modernism by focusing on ‘essence’ alone.

The End of Time exhibition will also feature Sugimoto’s Architecture series, another of prominent importance to the contemporary conceptual art world. Iconic 20th-century landmarks such as Empire State Building by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, Le Corbusier’s Chapel de Notre Dame du Haut and the Church of Light in Osaka by Tadao Ando have been deliberately shot out of focus so as to redefine form and capture the ambience and soul of modernism by focusing on ‘essence’ alone.

“One of my main interests was in the history of 20th-century modernism, of which architecture plays a key part. All of a sudden there was a godless world we all had to live in, devoid of decoration. Architectural history, however, traces back the rare, beautiful and atmospheric icons of architectural evolution. I intentionally made the series out of focus because I’m looking to capture the spirit of these buildings rather than their shape – all the details disappear and only the spirit of the building remains. Post-modern architecture is hard to photograph because there’s nothing there. There’s no core, it’s superficial and cheap. Many living contemporary architects call me and say, ‘I have this great new building. Please, please come and photograph it!’ But if I’m asked, I’ll never do it. This is my policy. There’s a certain purity in having choice and free will. I prefer dead architects – as they don’t beg me to photograph their buildings!”

Sugimoto, who spends half his time in New York, is well aware that photography as an art form faces new challenges in the digital era. His 19th-century view camera is a relic and he notes that the large format film he uses is also now in short supply. Kodak actually stopped producing the film, so Sugimoto had to switch to Fuji in the knowledge that they too could stop production at any time. The fiber paper he uses for his prints is also becoming increasingly hard to come by. But Sugimoto’s concept of time – how and when things begin and end – is far from conventional and it is this fundamental principle that gave rise to the title of his current exhibition.

“The words ‘End of Time’ to me don’t sound too pessimistic,” he says. “The concept of time, whether it’s beginning or ending, is abstract. The end of time suggests the end of culture, of humans, the disappearance of civilization… There must be an end to all these things, this is inevitable, but what about time itself, does that end too? In a sense I’m posing a question, what is time? Through my art and my show I’m trying to make people think. Time can’t be described in a single word or sentence, but the concept of time can be softly suggested.”

Story by Jonathan Day

From J SELECT Magazine, November 2005

Recent Comments