It may very well be scorching hot outside but there’s no excuse for staying indoors this summer, writes Suzanne Kamata.

Summertime, and the humidity is rising. The lure of air-conditioning may be strong, but there’s lots of seasonal fun to be had beyond the walls of your 3LDK. Check out the suggestions below, fill up your thermoses with mugi-cha (barley tea) and get outdoors.

Catch a Bug (or just write a Haiku)

As cherry blossoms are to spring, so insects are to the Japanese summer. The long hot days are filled with the screech of cicadas and department stores stock up on long-handled nets and cages for keeping bugs. The most prized are stag beetles, which are sold in pet stores. If you want to catch them yourself, you need to head to a wooded area. You can try stuffing an old nylon sock with a mashed banana and leaving it near a mulberry tree in the evening. If you check early the next morning, you just might find you’ve snared one.

For the creature’s comfort, you should fill a vented bug box (which looks like a small plastic aquarium) about half full with dirt. Scatter some leaves over the dirt and be sure to provide a piece of wood for it to hide under or climb on. Keep the box away from the sun and in a place where it’ll get sufficient ventilation. Special stag beetle feed can be bought, but the bugs are rumored to enjoy fruit such as watermelon, peaches and apples, as well as jelly, honey and yogurt.

If you find catching and confining insects a dubious sport, consider an evening of firefly viewing, another traditional Japanese activity. Fireflies, or lightning bugs, tend toward clean water, so try a riverbank or one of the many firefly viewing festivals in your area.

If you find catching and confining insects a dubious sport, consider an evening of firefly viewing, another traditional Japanese activity. Fireflies, or lightning bugs, tend toward clean water, so try a riverbank or one of the many firefly viewing festivals in your area.

Beach Antics

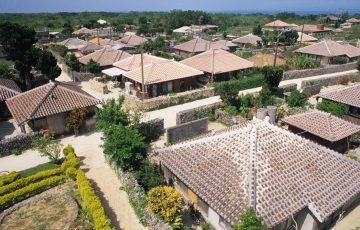

With so much water all around, you’d think that Japan would be full of great beaches, but this isn’t so. The best beaches can be found in the Ryukyu Islands. Those nearest Tokyo, around Kamakura and the Izu Peninsula, tend to be crowded throughout the summer season and most Japanese beaches don’t have lifeguards. Still, going to the beach is a standard summer activity, even in this country. From umibiraki (the opening of the sea) in mid-July till about mid-August, when the jellyfish become a threat, takoyaki, ramen and kakigori (flavored crushed ice) vendors set up their wares in tents along the shore and children take to the waves. Many beaches rent parasols and floating devices, but you’ll want to be sure to bring your own watermelon. For an authentic Japanese beach experience, you’ll need a long stick, a blindfold and a watermelon. The melon is placed on the ground. Players take turns being blindfolded and try to break the watermelon with the stick. Once the fruit is cracked open, everyone can dig in and eat. This game, similar to the pinata-smashing game played at American birthday parties, is traditionally played at the beach because it’s so messy. With the ocean near by, you can just skip down to the water and rinse the juice off.

Go Camping

Got a tent? If so, you can pitch it at any of hundreds of campsites in Japan. (Camping wild is generally frowned upon.) If you don’t have one, most campgrounds rent out tents, sleeping bags and other equipment.

Hokkaido, with its moderate summer temperatures and abundant nature, is considered prime camping territory. There are more than 100 campgrounds, some of them free of charge. Nagano, where the ski slopes of winter become the hiking trails of summer, is another popular destination. At Togakushi Campground (0262-54-3581), campers can indulge in fishing, paragliding and soba-making classes. More than 100 kinds of birds flutter through the pristine forests, making this a great spot for bird-watching.

Most campgrounds have showers and electricity at the very least. Others offer bike rentals, canoeing, RV hook-ups and the option of staying in a bungalow. Some, such as the KOA Campground in Tokuroshi, Fukui prefecture, have access to hot springs. Incidentally, the six KOA campgrounds in Japan are open year-round and reservations can be made in English at the KOA website (http://www.koa.com/where/japan). The majority of Japanese-run facilities operate on a seasonal basis. Remember, July and August are the months for camping in this country, so reservations are usually required.

Get Spooked

In summer, haunted houses sprout up across Japan. Traditionally, Japanese told ghost stories in the hot months because, in theory at least, the chills running down the listeners’ spines provided relief from the heat. In mid-August, it is also said that the spirits of the dead return to earth. There’s likely to be a haunted house near you. If you’d rather indulge in a round of telling ghost stories, you might look to Lafcadio Hearn’s Kwaidan and In Ghostly Japan. For those of you interested in spinning your own tales, a few characteristics of Japanese ghosts: they are usually one-eyed, sometimes lacking feet and/or faces.

Ichi… Ni… San

Rajio taiso, or radio gymnastics, are a staple of Japanese sports festivals and PE classes. This series of warm-up exercises, performed to a chirpy piano tune, was first developed in the 1920s. Japan’s participation in the 1912 Olympics resulted in a fitness boom, which led to the establishment of National Physical Education Day in 1920. According to the Ministry of Education, the holiday was meant to indoctrinate “collective behavior, moral training and aspiration of national spirit.” Rajio taiso, performed collectively, sometimes even in stadiums, fit neatly into the program.

Although western exercise gurus would probably denounce the routine as being bad for the joints, the jerky, bouncy movements seem to invoke nostalgia in many Japanese. Radio gymnastics in their original form have endured and even spread to TV. During summer vacation, children are encouraged to gather and exercise, often at shrines, in order to maintain a regular schedule and a healthy lifestyle. Kids can get cards stamped after each session for a feeling of accomplishment.

In summer, rajio taiso might give you and your family a reason to get out of bed early in the morning.

Let’s Celebrate!

Japanese festivals are held for a number of reasons. Some, such as the Obon festivals of August, welcome the spirits of the dead who are said to make a homecoming at this time. Others were originally held to celebrate the end of a plague or to ensure a good harvest. The Nebuta Matsuri in Aomori is meant to chase away the sandman who allegedly makes people drowsy in summer. Sanno Matsuri in Tokyo, which includes a parade of men and women dressed in Heian era attire, commemorates the annual appearance by the shogun who had the Heain Shrine built for the protection of his castle. In addition to the more famous festivals, numerous village celebrations are held.

The festivals of summer are invariably colorful and lively, providing plenty of photo-ops. Children will enjoy the booths selling masks, goldfish and grilled corn. Beer flows freely and people are generally relaxed and friendly.

While most festivals are public spectacles, you can decorate for the Sendai Tanabata Star Festival at home. Observed throughout Japan on July 7, this festival is based upon a Chinese legend featuring a weaver and her lover, a herdsman, represented by the stars Vega and Altair. Their love for each other was so great that they became idle and were punished by the king of heaven, who exiled the lovers to the opposite ends of the sky.

He permitted them to meet only once a year – on Tanabata. In Sendai, where Japan’s largest Tanabata Festival is held from August 6-8, the story is reenacted on stage. In homes and schools across the country, children write wishes on paper and tie them to bamboo branches. Supposedly, if the night is clear and the lovers are able to meet, the wishes will come true.

Take me out to the Ballgame

By this time, everyone knows that Japanese baseball is world class. Spectators at a professional game in Japan may well be watching next year’s Major League star.

For those just off the plane, Japanese professional baseball, now in its 70th year, is divided into two leagues: Central and Pacific. The six teams in the Central League are all based in the Tokyo area. Three of the Pacific League’s central teams are in Osaka, while the others are based in Hiroshima (home of Japan’s finest outdoor ballpark), Nagoya and Fukuoka, where you’ll find the only ballpark in Japan with a retractable roof. The majority of Japanese baseball fans follow the Yomiuri Giants.

Although it may be difficult to get tickets to a professional game this late in the summer, you probably wouldn’t have too much trouble getting in to see a minor league game. The farm teams don’t get much media coverage, so the games don’t attract many spectators. While you’ll have to bring your own snacks, the tickets are often free and you can sit by the dugouts, take photos and get autographs.

Unlike American minor league baseball which is divided into three levels (A, AA, and AAA), there is only one level in second-string Japanese baseball. Also, the lower level teams generally play close to home. The Giants minor league team plays at Yomiuri Giants Kyujo in Kanagawa prefecture (get off the train at Keio Yomiuri land station), while the Hanshin Tigers farm team plays at Hanshin Naruohama Kyujo (Mukogawa-danchi station) three stops east of Koshien, along the Osaka Bay waterfront.

Hanshin Koshien is home to the Hanshin Tigers, winner of last year’s Central League. It’s also the site of Japan’s national high-school baseball tournament. Nowhere will you find baseball played more passionately. In August, TVs and radios all over Japan are tuned in to these games but if you’re in the area, check out Japan’s future pros live.

Before you go, bone up on Japanese baseball by reading Robert Whiting’s classic You Gotta Have Wa. For more on cross-cultural baseball, check out Whiting’s new book, The Meaning of Ichiro, or Slugging it Out in Japan by former gaijin player Warren Cromartie.

Fish with Fowl

With water all around, families who fish shouldn’t have too much trouble finding a place to cast a line. However, for a more unusual fishing experience, you should head to Gifu or Kyoto prefectures. There, you can board a boat and watch as cormorants catch your dinner. The birds are tied to the boat with enough slack that they can dive into the water and catch fish – usually ayu, which are lured by a small fire burning in a metal basket at the bow of the boat. A metal ring around the cormorants’ throats prevents them from swallowing and the fish are retrieved by crew members. This practice dates from at least the eighth century. Now, the birds catch fish mostly for tourists in the summer months. Moonless nights are the best time to go. Fishing trips are usually canceled during and after a downpour.

Take a Hike

Although Mount Fuji is open all year round, the official climbing season is July and August. During that time, around 190,000 people climb to the top every year. Although all kinds of people, from small children to the elderly, make the ascent in summer, it’s best to be prepared. The air is thin at the summit and the weather can change rapidly. You’ll need clothing for cold and wet weather, drinking water and snacks, as well as a flashlight if you’re planning to climb at night.

Most climbers try to make it to the top before dawn to watch the incredible sunrise – Go-raiko, or The Honorable Coming of the Light. The mountain is often shrouded in clouds, but early in the morning you just might get a clear view.

There are 10 stations on the mountain, from base to summit. The majority of climbers start from the fifth station – Go-gome. Buses run daily from Tokyo to the Kawaguchi–ko fifth station during peak season. From there, it’s about a five-hour hike to the top. Mount Fuji is dotted with huts selling exorbitantly priced meals and offering mattresses for rent. On your descent, you can try scooting down the volcanic sand slides.

*All photos used in this article courtesy of the nagano convention bureau & convention bureau yamagata through the japan national tourist organization (c) JNTO

From J SELECT Magazine, August 2004

Recent Comments