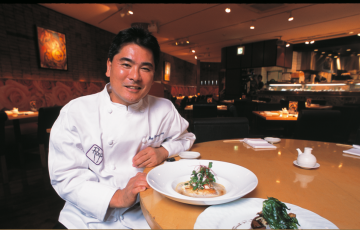

Still boyishly handsome at 62, there is no doubt that Kitahara is the boy with the most toys – in the world. Internationally, he is a renowned toy collector, having published seven books in Germany and five books in the U.S. about collectible toys. His collection at Epcot Center, featuring mainly tin toys made in early postwar Japan, has been so well received the exhibit is extended to run until 2010. Sotheby’s auction house knows him on a first-name basis. Kitahara’s hobby has garnered him many a famous pal such as

Still boyishly handsome at 62, there is no doubt that Kitahara is the boy with the most toys – in the world. Internationally, he is a renowned toy collector, having published seven books in Germany and five books in the U.S. about collectible toys. His collection at Epcot Center, featuring mainly tin toys made in early postwar Japan, has been so well received the exhibit is extended to run until 2010. Sotheby’s auction house knows him on a first-name basis. Kitahara’s hobby has garnered him many a famous pal such as

Demi Moore who shares his love of modern art and has visited his Kanagawa homeAnd when Pixar Studio’s John Lasseter visits Kitahara’s warehouses, it is hard to get him to leave. Lasseter’s fascination for curios goes beyond toys. “John is extremely curious and excitable,” remarks Kitahara who remembers Lasseter’s fascination with early generation vending machines and handcrafted antique push car toys.

Within Japan, Kitahara is most famous for being a collector of vintage tin toys, but he is so much more. Kitahara now operates seven toy and antique museums, with another one opening near Lake Kawaguchi later this year. Of the 59 books he has published, they are dispersed in all sections of a bookstore, the genre ranging from pop culture and Showa history to business management and personal essays. Perhaps the most intriguing are the craft books for grown-ups he co-authors. To build one of the figures requires 60 hours of construction – providing you don’t go wrong. “Sixty hours! It’s crazy isn’t it?” he laughs. “But when people complete such a complex project, they have a strong sense of satisfaction. They send me pictures of their completed projects and I display them at my shops,” he says.

Born in Tokyo in 1948, Kitahara considers himself a representative of Japan’s Baby Boomer generation that shaped the country’s postwar history. The dankai (baby boomer) generation was made up of political agitators and folk song lovers as students. Later they poured their passion into work as corporate samurais. Kitahara does not quite fit into either group. But what he shares with his generation is a passionate drive to strive for the best and a fierce work ethic.

“No matter how old or young you are, achieving a goal is a matter of practice and patience. No one can start off doing 100 sit-ups the first time they try, but start by doing ten, then increase it by the week, and before you know it, you will be pushing yourself to do 110!” he says with conviction.

At 62, Kitahara is bronzed, muscular and welcomes being photographed wearing only a bikini brief. He is quick to smile and his eyes always have a mischievous twinkle. Kitahara begins his day with a simple work out regime. Golf is his current passion. Having begun in his 50s, he has reached a level of competency that has made him the poster boy for Bridgestone, the golf equipment manufacturer. Playing the guitar is another hobby he took up in middle age, and with daily practice, he has played at the coveted music hall Budokan as a guest performer with his idol Yuzo Kayama.

As the son of a sports shop owner, Kitahara acknowledges he grew up fairly affluent, though it was during a time when Japan was poor. An avid skier, when Kitahara was a university student, he went on a trip to Europe to hone his mogul skills. But more than the powder snow, it was the well-preserved antiques in Switzerland that left the bigger impression. When he returned to Japan, he vowed to become a collector of nostalgic memorabilia.

As the son of a sports shop owner, Kitahara acknowledges he grew up fairly affluent, though it was during a time when Japan was poor. An avid skier, when Kitahara was a university student, he went on a trip to Europe to hone his mogul skills. But more than the powder snow, it was the well-preserved antiques in Switzerland that left the bigger impression. When he returned to Japan, he vowed to become a collector of nostalgic memorabilia.

When Kitahara first began collecting toys in the 1980s, there was no one else doing it on a systematic scale. “I attended lots of local flea markets all over the country,” he said. “I love the feeling of going on a treasure hunt, not knowing what I’ll find. I know Internet buy and sell is very popular, but for me, it is the interaction with the sellers that is intriguing. By buying directly from them, I can get a sense of the object’s life story,”

Kitahara chose only products that were in good condition, well crafted and had some nostalgic impact on people. “I only want things that were well-loved by their owners enough to be kept in good condition. No matter how rare something is, if it is in a bad condition, I consider it junk,” says Kitahara who puts great emphasizes on boxes. “The box tells the history of the object,” he explains.

Kitahara specialized in the tin toys of made in the postwar Showa period. “Japan was a poor country then. But even with low priced tin toys, the craftsmen put such painstaking details into every creation. It is the spirit of these artisans that I adore,” says Kitahara. “But most Japanese couldn’t afford these toys so they were made for exporting,” Kitahara says as he shows pictures of robot toys made in the 1950s with boxes labeled only in English. At a Sotheby’s auction, one of these robots now fetch around $50,000 USD.

In his office, Kitahara has a special collection of pencil sharpeners. In the Showa period, Japanese kids could only afford these types of small trinkets. Peering into the glass case is like going back in time to understand how kids back then thought were cool – robots, sports cars and Babe Ruth. Kitahara says the American baseball legend was so popular in Japan, pencil sharpeners replicating the Bambino’s chubby face were eagerly sought after.

In the 1980s, though Kitahara’s collection was beginning to become extensive, he was hardly a household name. Collecting was still a hobby while he worked for his father’s business. Then about 15 years ago, he began to appear on a popular television program that appraised old objects people had in storage. There were traditional antique appraisers evaluating the value of Edo period tea bowls, but Kitahara captured people’s imagination by placing value on toys everyone remembers playing with as kids. He became so known for being a toy expert that, in 1985, he opened his first museum in Yokohama, the Tin Toy Museum, and he hasn’t looked back since.

That Kitahara is a millionaire by simply enjoying his hobbies makes him an icon amongst men/boys. “Men are different from boys in the sense that they work hard to pay for the toys they want,” he emphasizes. Yet Kitahara never really seems like he’s working. Like anyone successful, he experiences failure. But he is also a master of positive thinking and considers every setback as a challenge to become better. A popular speaker on the public lecture circuit, he gives about 15 talks a month. He appears on two television shows regularly and speaks on three radio programs. Kitahara acknowledges that he earns a sizeable income. Some objects he bought for ¥5,000 now sell for ¥1,500,000. “But I don’t have a yen in saving,” he says with pride. “Everything I earn, I put towards expanding my collection.” The most costly object in his collection is his Yokosuka home. Originally built in the 1930s, his house is the only remaining “boathouse” in Japan, where a dock for small sailboats is built into the basement. It took almost a decade of persuasion to get the former owners to sell it, but Kitahara knows what he wants and gets it. On the property are two spacious houses, the larger one being his private home, and the one perched on the cliff overlooking the ocean is his guesthouse. Both structures are of course filled with Kitahara’s favorite objects. He frequently hosts extravagant parties at his home. “I have up to 200 people at my parties. I figured out how to make this possible by not getting people to take off their shoes! Imagine the chaos of organizing 200 pairs of shoes in your entrance? By doing it Western style, I can now invite as many people as I want,” he says.

Kitahara has been criticized for hiking up the prices of memorabilia, but he points out, “Even I am surprised by the prices some of these items fetch. Ultimately, it is not me but consumers who determine the prices of these goods. If the desire for them falls, the prices will as well, ” he defends. “Human beings are the only living things who collects things they don’t need,” says Kitahara. “What I find peculiar about Japanese collectors is their reluctance to show others what they have. It’s always ‘What I have is nothing’ whereas collectors in other countries love to show and talk about what they have. When you are communicating about something you have passion about, it’s always exciting. A collection should not be hidden away but should be displayed as a part of your everyday life,” he says. “Collecting is about bringing joy into your own life.”

Kitahara has been criticized for hiking up the prices of memorabilia, but he points out, “Even I am surprised by the prices some of these items fetch. Ultimately, it is not me but consumers who determine the prices of these goods. If the desire for them falls, the prices will as well, ” he defends. “Human beings are the only living things who collects things they don’t need,” says Kitahara. “What I find peculiar about Japanese collectors is their reluctance to show others what they have. It’s always ‘What I have is nothing’ whereas collectors in other countries love to show and talk about what they have. When you are communicating about something you have passion about, it’s always exciting. A collection should not be hidden away but should be displayed as a part of your everyday life,” he says. “Collecting is about bringing joy into your own life.”

Contemporary Japanese Artists

Teruhisa Kitahara always had interests beyond tin toys and robots, although he is most famous for these collections. While he still collects the latest robot toys, he prefers not to discuss how current mass-produced toys do not reflect the spirit of craftsmanship as toys in the past. Rather, he is quick to divert the topic to discuss where he does find creations that reflects ideals he cherishes – contemporary, little-known Japanese artists. As a hit-maker, slowly the exposure Kitahara gives them increases the value of these artists, creating a win-win situation in the world of Japanese modern art.Some of his favorite artists include the recently deceased painter Yuji

Kamosawa, whose motifs are whimsical yet macabre. In one painting, a sickly looking boy is connected to a dismembered mannequin with his internal organs revealed. Outside the window, fluffy clouds float in a pastel sky with the planet Saturn looming large. “People are just beginning to appreciate the creative genius of this artist,” says Kitahara who owns 90 percent of Kamosawa’s work.

Another artist that fascinates the collector is Shinichi Yamashita. He first spotted Yamashita’s figures with the motif of angels in a style blended of Rococo ornate and Japanese patterns. He contacted Yamashita to create a line of female figures that are sci-fi erotic. The female figures are nude, wearing various styles of clothing and all are enclosed in clear glass cases. Kitahara lines his Yokohama office with over twenty of them. Looking at them closely, each has a distinct, almost haunting expression.

A third artist Kitahara fancies is Hiroshi Araki. Kitahara first became fascinated by this artist with a sculpture he did of “Astro Boy.” What attracted Kitahara to Araki’s work is how the artist incorporates sound as a medium. “This guy goes out and finds Phillips speakers made 50 years ago with incredible acoustics,” raves Kitahara who commissioned Araki to build a huge speaker shaped like a robot, displayed prominently in his Yokohama office. He turns on the speakers to play an old LP record.

The room is just enveloped with alto saxophone. “It’s more than just creativity. How Araki painstakingly finds old sound equipment for his art shows the kind of devotion I adore,” explains Kitahara. In the next decade or two, look for these artists, not at Epcot Center but perhaps at the Guggenheim in New York.

Story by Carol Hui

From J SELECT Magazine, May 2008

Recent Comments