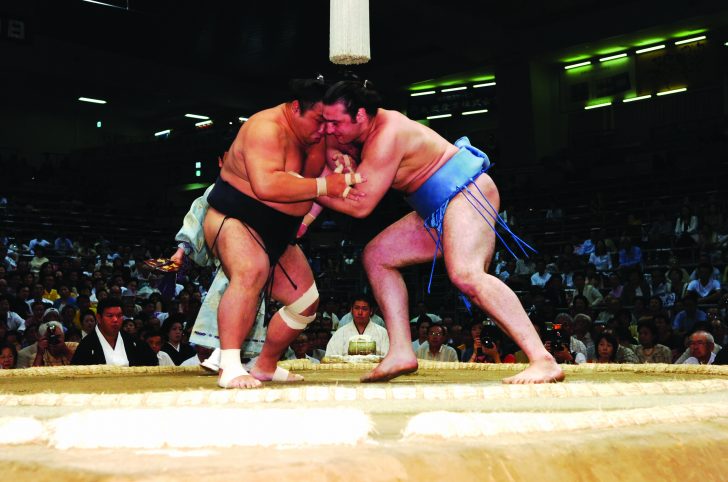

Twenty-three-year-old wrestler Kotooshu breathed some much-needed life into the stagnant sumo competition last year with a couple of upset victories over grand champion Asashoryu and promotion to the rank of ozeki in record time. Is he the Great White Hope that sumo has been waiting for? Keith Robson reports…

The recent actions of the Japan Sumo Association make it difficult to work out quite where it stands on the issue of foreign participation in the sport. Although it will not go so far as to admit foreigners were ever barred from participating in Japan’s heavyweight pursuit, sumo stables up and down the country were “discouraged” from recruiting foreign wrestlers for a five-year period during the 1990s. This period more or less coincided with the Taka-Waka boom, during which time Takanohana and his elder brother Wakanohana created immense interest in the sport and ticket sales skyrocketed as a result. Ironically, it was during this boom that Akebono became the first foreigner to reach the exalted ranks of yokozuna (grand champion). Sumo hasn’t really been the same ever since.

Sporting booms in Japan only last as long as the stars that create them, and once that star wanes the enthusiasm behind the boom’s newfound popularity quickly dies out unless a new hero emerges from the darkness. The first star to emerge in the wake of Takanohana and Wakanohana was Asashoryu, a Mongolian wrestler who zoomed up the promotional ladder to become the third foreign yokozuna after Akebono and Musashimaru. The stocky wrestler has since gone on to dominate the sport, a fact that certainly hasn’t pleased the homogenizers of the racial world in Japan (even though, as a Mongolian, he is of the same race as the Japanese). While Akebono played fair and lost as much as he won, Asashoryu realized fairly early on in his career that most sumo wrestlers – especially Japanese wrestlers – were powder puffs that deserved to be treated with contempt. In fact, for a while Asashoryu appeared to be treating everyone – including the sport itself – with contempt, which sparked several “We don’t need Mad Mongols” headlines in the local press.

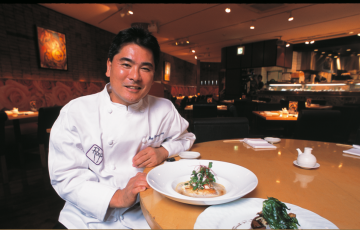

So, what to do with a handsome, 203-centimeter white boy from Bulgaria? Since his arrival in Japan’s sumo world, Kotooshu has shot up to ozeki (sumo wrestler of the second highest rank), one rank below yokozuna, and become a media darling. He’s tall, white, charming, handsome, polite and successful. Moreover, he’s not fat or loud, belligerent or mad and – better still – not Mongolian. Although sumo’s conservative forces might still be choking on their chonmage (topknot), it’s perhaps not surprising that the mainstream media are jumping all over the 23-year-old boy from Bulgaria. In turn, young women are going nuts over the handsome former wrestler and the Japan Sumo Association is even allowing sumo stables to recruit one foreigner per stable. For his part, however, Kotooshu doesn’t have a strong opinion on such matters. “If that’s what they say the rule is, then that’s what it is and I can’t really say anything about it,” he says during a recent interview at his stable in Matsudo.

His stablemaster, Sadogatake, who fought under the name Kotonowaka and retired recently having reached the rank of sekiwake (sumo wrestler of the third highest rank), says it’s not necessarily about how many foreigners you can recruit but how many can stay the course. “We’ve had many foreigners come here,” the affable and cheerful chap says over an excellent lunch of kimchi-spiced chanko nabe (stew). “But they just couldn’t stand the pace. The training was too hard for them and they gave up.”

Adapting to life in the beya can also prove difficult. Former ozeki Konishiki once told Tokyo Journal that he was hit over the head with a bottle at his stable for not taking the trash out properly and it is probably no coincidence that both he and Asashoryu seem to relish beating Japanese opponents on the dohyo. Of course, most of us have been figuratively smacked around the head with a bottle at some stage on our long journey into Japanese culture but sumo is often seen as a defender of Japanese culture, not just as a sport. “Sumo is a traditional sport,” Kotooshu says. “The tradition comes first and the sport comes after that. It’s important to abide by the traditions and rules.”

When asked if he’s ever had negative experiences because he’s a foreigner in sumo, Kotooshu sidesteps the question. “Well, you just have to keep your focus on your training and keep winning,” he says. We’ll take that as a yes, then. But it should be pointed out that sumo is founded in a feudal environment. The system is not designed to be fair or democratic; it’s designed to be severe and to test the resilience of those who want to join its exalted ranks. Being a successful sumo wrestler is like joining an elite stratum in society, and the chonmage, the kimonos, the girth, the attendants and the rituals all help to distinguish the sumo wrestler from the common man. Take the pain and you will reap the gain, seems to be its motto. It’s all part of tradition (bottles to the head not included, of course).

Before dedicating his life to sumo, Kotooshu was already heavily involved with another traditional sport: wrestling. (It’s worth just noting here that Asashoryu was also a wrestler – a Mongolian wrestler – before taking up sumo.) Kotooshu was no dummy wrestler, so the discipline and dedication needed to succeed had already been part of his conditioning. “I was aiming to go to the Olympics in 2004,” he recalls, adding that his all-time hero was Russian Greco-Roman wrestling legend Alexander Karelin. “I was 21 in that year and my body was in really good shape. But after the Sydney Olympics in 2000, they lowered the weight limit for the event from 130 kilograms to 120 kilograms. By the time I was 17, I already weighed 130 kilograms so I had to look for something else. “Apart from doing wrestling, we used to do sumo just for fun. I enjoyed doing it and I always used to wonder what kind of sport it really was. More importantly, you didn’t have to worry about your weight, which was obviously good for me.”

Now weighing 147 kilograms, Kotooshu is hardly overweight by sumo standards and taking his height of 203 centimeters into consideration, he’s almost slender. Akebono, who is roughly the same height as Kotooshu, weighed nearly 100 kilograms more when he was yokozuna. “If I was any lighter, it would be hard to perform well in sumo, especially as I’m tall and big-boned,” Kotooshu explains. “In sumo, you have to keep your body big.”

This is usually done by consuming outrageous amounts of food, especially chanko nabe and rice (not to mention plenty of beer). “I keep an eye on how much the youngsters eat and, if necessary, get them to eat more so they can become bigger,” reveals the imposing figure of Sadogatake, pointing to a 145-kilogram, 15-year-old understudy in his stable. Kotooshu admits to having had transitional problems with the Japanese diet at first. “When I first came here, I didn’t eat rice at all,” he says. “It had no taste. I liked it when it had some spice in it, like fried rice.” Kotooshu no longer has a problem with the food and it’s perhaps easy to understand why: the kimchi-flavored nabe offered to the J Select crew with an early morning beer was outstanding and we all came away noticeably heavier.

However, food wasn’t the only concern on the young Bulgarian’s mind when first beginning life in the strange world of sumo. “The two hardest things were the training and the language,” he says in excellent Japanese (he also speaks Russian and a little English). “You can’t really do anything without knowing the language of the country you are in. Back then, I couldn’t communicate with anybody.” Total immersion soon solved that particular problem. Kotooshu says he didn’t have time to attend language school and he was forced to learn from his fellow wrestlers. Nevertheless, it was tough being alone in a foreign world, away from family, friends and his own culture. “I had no friends and I didn’t know a word of Japanese. I couldn’t figure out what they were saying on TV so I would often just be by myself, alone,” he recalls. “I felt quite lonely.”

Although he will not be drawn on his love life, the handsome giant now has a huge following among female fans. It hasn’t hurt him that he now speaks excellent Japanese, is polite, charming, funny and has a smile that can kill at 20 paces. Has he noticed any differences between Japanese women and Bulgarian women? “No, they are all the same,” he says diplomatically. “Some are nice and some are not.” And Japanese women? “They are very pleasant and very kind,” he admits bashfully. “When I first came here, I didn’t know what they were like because I couldn’t speak Japanese. But as my Japanese improved, I was able to have conversations with them and I discovered how nice they are.”

Kotooshu is now one of the most recognizable faces in Japan. How is he coping with this sudden fame? “It has its good points and bad points,” says the big Bulgarian, who was renowned for sleeping all the time upon first arriving in Japan. “These days I can’t go outside. Also, I don’t really have time to myself any more. I wish I could take more of my own time to relax but sumo wrestlers are busy all the time.”

He does occasionally escape and professes a liking for Mount Fuji and onsen, particularly rotenburo, where he can relax in peace. When he does have a little time to enjoy himself, he plays soccer or basketball, and listens to Eminem and 50 Cent. But his soul, it seems, is still in Bulgaria. When asked which team he would support in the Kirin Cup soccer match between Japan and Bulgaria, he answered without hesitation: “I want Bulgaria to win.” You can take the boy out of Bulgaria…

“The toughest part for me is that I don’t have enough time to go back to Bulgaria,” he confesses. “I miss my family.” Home for the man born Kaloyan Stefanov Mahlyanov is Veliko Tarnovo, a provincial capital of 73,000 people in northern Bulgaria where he grew up with his parents and an elder brother. After graduating from high school, the tall teen went to university in Sofia on a sports program. As a kid, he was into soccer. Bulgarian soccer was very strong at the time and was led on the field by Hristo Stoichkov, who would end up playing for Kashiwa Reysol in the J.League (the two have met). Despite being a fast runner, however, Kotooshu admits his career did not lie in the beautiful game. “I was the goalkeeper,” he says with a laugh.

He also participated in swimming but eventually settled on wrestling. With his Olympic dreams dashed, he quit university and came to Japan, where his success was instantaneous. He made his debut in November 2002 and had a 71-15 record in sumo’s lower divisions. He kept up his winning ways after promotion to the Makuuchi Division and had three consecutive winning records, which earned him promotion to komusubi (sumo wrestler of the second highest rank). After a brief demotion due to a losing record, he returned to the sanyaku ranks (the three ranks below ozeki and yokozuna) and in July 2005 ended Asashoryu’s 20-bout winning streak. In the very next basho, he came close to taking home his first title when he took the grand champion to a winner-takes-all playoff but ultimately failed at the final hurdle. On November 30, 2005, three years after his debut in sumo, he was promoted to the rank of ozeki. It had taken him just 19 tournaments, the fastest rise ever for a wrestler from the lowest ranks of sumo. Now, he is being seen as the Great White Hope, the man to challenge the supremacy of the “Mad Mongolian,” Asashoryu.

“It’s not just about Asashoryu,” Kotooshu says. “I have to beat everybody. Of course, everybody is nervous when they face him for the first time. I don’t remember if I was confident of beating him, but I just wanted to bring out my best stuff. After that, whatever happens, happens. But I think that I still have a lot to learn in sumo.”

And perhaps sumo has a lot to learn from him. At 23, the mild-mannered man of steel is the acceptable foreign face of a very Japanese sport. His elevation to the rank of yokozuna is not assured, but, injuries permitting, highly likely. If so, he would be the first Caucasian yokozuna and that feat alone would do more than anything else to bring sumo to the world. World sport, after all, is largely run by the white man and the white man’s money. Sumo’s policies have yet to tally with its international ambitions but in Kotooshu the sport perhaps has the quintessential missing link. The big Bulgarian with the homespun charm and winning smile may have more on his plate than he realizes.

Interview by Keith Robson (Interpretation by Andy Hunne), Portraits by David Stetson

From J SELECT Magazine, July 2006

Recent Comments