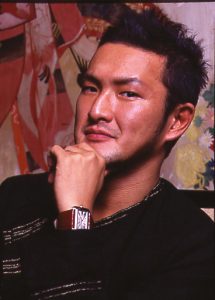

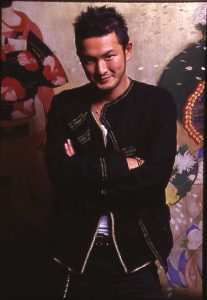

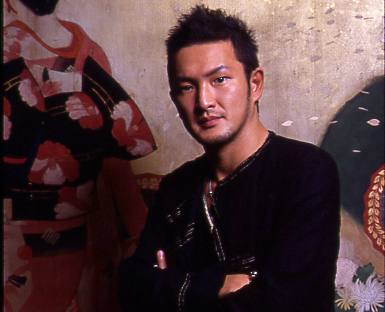

Few performers in Japan have been able to make the leap from the kabuki theater to the silver screen – and vice versa – without falling foul of the critics. One actor who has successfully managed to keep a foot in each court in modern times is Shidou Nakamura, who is using his experiences on stage and in front of the camera to bring considerable depth to the characters he plays in either genre. And yet even this synopsis sounds a tad simplistic; there’s more – much, much more – to this imposing performer than meets the eye. What on earth is it? Story by Alicia Kirby. Photography by David Stetson. Shot on location in Meguro Gajoen, Tokyo.

As he casually lolls into the room, clad in black from head to toe, there is something about actor Shidou Nakamura that arrests the attention of everyone present. What exactly is it?

Perhaps it is his couture biker apparel, which completes his finely tailored, carefully thought-out “rugged” look? Or perhaps it is the fact that he looks so devastatingly handsome he could have just stepped off a catwalk situated nearby? Then again, it could be the effect of his oversized shades in a dimly lit room. Whatever it is, Nakamura possesses a certain je ne sais quoi that screams “movie star.”

Refreshingly, however, achieving the status of celebrity does not appear to be on his agenda.

“I don’t really care about being famous,” says Nakamura as he sits around a mother-of-pearl lacquer table in a private dining room buried deep in the heart of Meguro Gajoen in Tokyo. “I just want to be a good actor.”

Born in 1972 into a prestigious family of kabuki actors, Nakamura is one of an unusual breed of burgeoning Japanese stars who have defied convention by making the transition from the Kabuki stage to the silver screen.

Indeed, one of the few to win accolades for performances in both genres is in fact one of Nakamura’s uncles – Kinnosuke Nakamura, also known as Kinnosuke Yorozuya. Renowned for his roles in Fuefuki Doji (1954) and Miyamoto Musashi (1961-1965), his uncle managed to carve out a successful film career that spanned four decades, a feat Nakamura says was extremely rare during that time.

“Back in those days, to be both a kabuki actor and be in film was literally unheard of,” he says. “The boundaries were much more defined.”

The influence of the kabuki world made a strong imprint on Nakamura in his childhood and he made his stage debut at the tender age of nine.

“When I was younger all my relatives used to take me to see kabuki plays,” he says. “My grandmother took me to the kabuki theater a lot and through watching these plays I naturally thought that I would like to be on stage too.”

That Nakamura was born into a kabuki family and his uncle was a famous movie star by no means meant his acting career was mapped out for him. He has always wanted to pursue a career as an actor and even studied drama at university, knowing he really “couldn’t do anything else.”

That Nakamura was born into a kabuki family and his uncle was a famous movie star by no means meant his acting career was mapped out for him. He has always wanted to pursue a career as an actor and even studied drama at university, knowing he really “couldn’t do anything else.”

In his youth, luck was not on his side insofar as his acting career was concerned and few challenging roles were offered to Nakamura in his twenties. Amidst endless talk in acting circles of a prospective career in film that never seemed to come to fruition, he finally decided it was time to take matters into his own hands.

It what is now regarded as a pivotal moment in his career, Nakamura came across an audition for an independent film called Ping Pong and decided he had nothing to lose.

“I was 28 or 29 at that point so I thought I should really go and do something off my own back, otherwise nothing would happen,” he recalls. “So I grabbed the chance and went to the audition.”

The rest, as they say, is history. He was cast in the role of Dragon, a menacing ping-pong champion who treats opponents with disdain, and impressed audiences so much he was awarded Best Newcomer at the prestigious Japanese Academy Awards in 2003. The Japanese film industry was certainly beginning to sit up and take notice.

After Ping Pong, Nakamura blew away the Japanese box offices starring in the hit romantic flick Be With You (Ima ai ni Yukimasu), in which he starred opposite his future bride Yukiko Takeuchi. In 2005, he dabbled in war action (Yamato) and art-house (Neighbor No. 13, or Rinjin 13-go) roles, before heading to Hollywood and starring opposite Jet Li as a judo master in Ronny Yu’s 2006 filmSpirit (which has since been released as Fearless in the UK and US).

Nakamura’s class and incredible versatility as an actor are more than likely to be deeply rooted in the vigorous kabuki training he undertook during his youth. Kabuki actors typically commence training as young as four or five years old, and are required to learn how to play various roles across a broad range of traditional and modern kabuki plays. These roles include the famous onnagata (female characters) that male-dominated kabuki theater groups are famous for.

His most notable role of late is in director Clint Eastwood’s latest project Letters from Iwojima,which will be released in the west as Red Sun, Black Sand. The film recounts the epic battle between US and Japanese troops on the tiny island of Iwojima during World War II and sees Nakamura star alongside another talented Japanese thespian export to Hollywood, Ken Watanabe.

When asked about the challenges and difficulties he faces when working outside of Japan, Nakamura makes an astute observation.

“I had some problems with the language when I was working as my English is not so great,” he says. “However, in terms of creating a work, the concept doesn’t change whether you are in America or Japan.”

Nakamura is excited to be involved in a project alongside Eastwood, a figure he reveres both as an actor and director. The most difficult part, he adds, is getting used to Eastwood’s idiosyncratic directing methods.

“The rumors that Clint hardly does any test runs are true,” he says. “In the beginning the set was really quiet and you would wonder when we were going to start but then you would realize the cameras were already running. There were quite a lot of situations like that. The fact that there were no tests makes you quite nervous and adds to the tension, but as an actor being on Eastwood’s set was an invaluable lesson… I learnt a lot.”

The tables have turned since Nakamura’s notable success in film and television, and kabuki theaters throughout Japan are now approaching him with a wide range of challenging roles. Nakamura performed at the Mitsukoshi Stage in Tokyo in June earlier this year, where he played the role of an evil oil merchant called Kawachiya Yohei in one of Chikamatsu Monzaemon’s masterpieces, The Woman Killer and The Hell of Oil (Onna Goroshi Abura Jikoku). Monzaemon is Japan’s most famous classical playwright – Nakamura rightly iterates the fact that he is revered as “Japan’s very own Shakespeare” – and his works are revered by anyone who follows Japanese literature. (The Woman Killer and The Hell of Oil and other selected works by Monzaemon can be found in professor Donald Keene’s excellent translation, Major Plays of Chikamatsu.)

Nakamura is also expected to appear in the lead role of Mori No Ishimatsu, a simple and selfless yakuza who is hell bent on avenging the death of his parents, at Shimbashi Theater from October 2-26.

Sons of other prestigious kabuki families in Japan such as the Ebizo family have also successfully followed suit and branched out into various roles in television and film. These are uncharted waters though for many of these aspiring actors, with most expected to follow a tradition that dates back some 400 years. Is kabuki going through a state of flux?

“I think some onus is on the younger generation to show audiences the beauty and appeal of classical Japanese theater as well as for new playwrights to take on the challenge of writing kabuki plays,” Nakamura says. “But the most important thing is to keep the audiences happy so that they enjoy what we produce.”

This trend is not merely limited to the younger generation of kabuki actors and even veteran actors such as the esteemed Tamasaburo Bando have been dipping their fingers into other projects outside of their traditional art. In May and June earlier this year, Bando performed in the role of Amaterasu in a visually stunning and unusual collaboration with the Kodo drum troupe from Sado Island in the Setagaya Theater.

Given Nakamura’s myriad kabuki roles and television appearances in Japan and abroad, one wonders how Nakamura manages to find any time for himself and his family, let alone bring up his recently born child, the result of a hasty and highly-publicized wedding between himself and the beautiful actress Yukiko Takeuchi. He relaxes by simply “shopping, mainly in Los Angeles,” which he is drawn to because of its “good weather.”

Nakamura’s soft and sensitive side emerges as soon as he speaks lovingly of his child and his new role in life as a father. He says the new responsibility has given him a different outlook on many aspects of his life, especially when looking back on previous roles in war films such as Yamato (his child was born just weeks before the premiere) and, more recently, Letters from Iwojima.

Nakamura’s soft and sensitive side emerges as soon as he speaks lovingly of his child and his new role in life as a father. He says the new responsibility has given him a different outlook on many aspects of his life, especially when looking back on previous roles in war films such as Yamato (his child was born just weeks before the premiere) and, more recently, Letters from Iwojima.

“It is strange being a father because I have realized a lot of things I didn’t realize before,” he says. “For instance, when I was working on films about the war, I only understood that Japanese soldiers had to leave their families to go to war as pure fact. Now I have my own child and the happiness my child brings makes me think deeper about what these soldiers had to leave behind.”

Even watching a movie, it seems, will never be the same again.

“If the main character the camera is focusing on is a young boy who, for example, says goodbye and then you hear the sound of the parent in the background saying goodbye, I now automatically think more about what the parent is saying and the tone of his or her voice, even if the film is not focusing on the parent and he or she is in the background. I have noticed I have become really sensitive and aware of this kind of stuff.”

Nakamura’s frank and open demeanor is refreshing. His dream is to continue playing as many varied roles as he can and continue cultivating his skills as an actor. With movie producers and theater operators at home and abroad lining up for the chance to have Nakamura appear in their next project, he appears able to do just this.

Some traditionalists are perhaps quick to rebuke young kabuki actors who decide to leave behind an art form that shoulders a 400-year history and a wealth of culture. They look down on the actors for not possessing the fortitude required to make the life-long commitment to their art. However such criticism cannot genuinely be leveled at Nakamura, who expresses an equal and ongoing commitment to both genres. Actors in modern times appear to be at the mercy of those who employ them (and not the other way around, as was the case in days gone by) and so it seems a little harsh to try to limit their activities when few guarantees can be made about the next paycheck. And even if an actor spends 30 or 40 years in the kabuki circuit, there is no assurance they will ever attain super-star status in the same vein as Danjuro Ichikawa and Tamasaburo Bando.

Young actors such as Nakamura are something of a godsend for ailing kabuki theaters in Japan, which had, until recently, been watching attendance figures drop at a steady rate. The new generation is now, more than ever before, in the public spotlight and the net effect of this seems to be more bottoms on seats. Given the elaborate sets and expensive embroidered costumes used in kabuki productions, theaters cannot really afford to perform to half-empty audiences and so it’s worth their while to use actors such as Nakamura as magnets for people who would not normally be attracted to a stage production – especially kabuki productions that are unique in that they challenge audiences on many different levels.

There is definitely something about Shidou that is drawing people back to the theater. As far as the future of kabuki is concerned, this can only be a good thing.

Story by Alicia Kirby

Images by David Stetson

From J SELECT Magazine, August 2006

Recent Comments