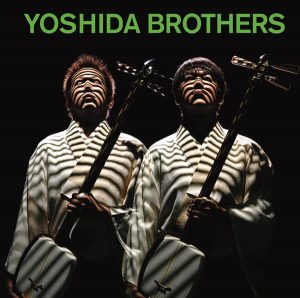

It’s hard to imagine a pair of mild-mannered tsugaru shamisen players from Hokkaido being able to whip difficult crowds in the United States into a frenzy, and yet that’s precisely what happened during a recent tour of America by the Yoshida Brothers, Japan’s answer to the Everly Brothers of the late fifties and early sixties.

Dressed in kimonos, Ryoichiro, 28, and Kenichi, 26(25), played to full houses at numerous venues in the US as word of their electric performances spread. Demand for their self-titled debut album has since skyrocketed, with young and old alike taking a shining to their deliverance of classical chord structures in a contemporary, upbeat style.

In Japan, the brothers have been a household name ever since they debuted in 1999. However the duo are quick to shun the glamorous side of their meteoric rise to fame, preferring instead to concentrate on educating young people and making sure the tsugaru shamisen tradition is passed on to the next generation.

Musical Melting Pot

The tsugaru shamisen is a three-stringed lute from northern Honshu’s Aomori prefecture, which many consider to be one of the most representative in terms of Japanese instruments. Originally from China, the shamisen was first introduced to Japan via Okinawa. Merchants eventually brought it to the mainland, trading its snakeskin for catskin and adding a few centimeters along the way.

The tsugaru shamisen is played in the same way a banjo is, with the musician plucking the three amplified silk strings to produce amazing vibrato sounds. The distinctive sound of the tsugaru shamisen goes hand in hand with most traditional Japanese performance arts. It is an essential element of sankyoku chamber music, kabuki and bunraku puppet theater.

The ancient tsugaru shamisen is a little larger than its Okinawan counterpart, and is characterized by an extremely energetic and fast-paced playing style combined with extensive improvisation and an irregular rhythm.

It’s a flexible instrument that gives experienced musicians plenty of versatility to work with when going through a composition. The Yoshida Brothers’ debut(6th) album is testament to this, with the pair able to combine Bulgarian themes, Brian Eno songs, tangos and traditional Japanese melodies. They spent more than two months working on it with musical virtuoso Tony Berg and it appears their hard work and dedication has paid off. Although each song stands alone, the distinctive sound of the tsugaru shamisen can be heard throughout and the album as a whole takes on a life of its own. For his part, producer Tony Berg loved working with energetic pair.

“It was a great experience,” Berg says. “They are extraordinary musicians and wonderful people. We attempted to create an album that is quite different from what they have done in the past. The eclecticism of the album is held together by the beauty and expressiveness of the shamisen and the remarkable musicianship of the brothers. Their shows and their original compositions give great insight into the brothers themselves. Kenichi is an extrovert, writing the more uptempo material, while Ryoichiro is more contemplative. His melodies are generally slower and more elegiac.”

Same Same But Different

In fact the brothers’ differences – and similarities – can be taken right back to an early age. Born in Hokkaido, the pair has been playing the shamisen together for almost as long as they can remember.

“We have been playing the shamisen from the age of five so we have a very natural closeness,” Ryoichiro says. “In a sense we are also rivals since we play the same instrument and I think that’s why we have developed our technique – we are always trying to get better faster than each other.”

Part of the brothers’ charm is the tremendous rapport they seem to have. So close do they appear to be in mannerism and thought that they – unknowingly or not – are able to finish each other’s sentences.

“I wanted to not only catch up but be better than him,” Kenichi retorts. “I don’t know if it worked but the two of us are always trying to improve our technique. In that sense we are pretty similar to craftspeople who are always in pursuit of the unattainable perfect work of art.”

The pair love being musicians now, but they admitted that practicing the shamisen as boys was traumatic.

“Imagine being five years old and studying with 55- and 65-year-old people,” Ryoichiro says. “Basically kids were not interested in the tsugaru shamisen at that time and we were considered weird and made fun of for wearing kimono and playing an instrument that was almost entirely reserved for the elderly. But our dad encouraged us not to quit so we kept on playing. The real fun, however, only came in our teens.”

“Now we are thankful that we persevered,” Kenichi says. “Of course it was great to have fellow students who were older than our grandparents because we learnt a lot about human psychology, acquired polite forms of expression and proper behavior. We grew up fast in a very positive sense.”

“Our teachers really encouraged us and insisted that we needed to get good at English, too so we could go out and bring our music all over the world,” Ryoichiro. “Sasaki Takashi(Takashi Sasaki- Sasaki is last name), who taught us in our teens, was particularly influential because he installed the dream and the discipline into us. Unfortunately he passed away five years ago so he doesn’t know we are doing what he had planned for us. He opened our eyes to the world but at the time we didn’t recognize how wonderful he was. Luckily we at least listened and kept on practicing.”

“Yes but it’s too bad we didn’t work even harder then,” Kenichi says. “We should have been more serious but we were too young to grasp what a great man we had as mentor.”

Dreams & Aspirations

The brothers count Hayashi Eitetsu(Eitetsu Hayashi- Hayashi last name), a virtuoso wadaiko drummer, as one of their main influences because he developed a wild style of playing not just one but many drums simultaneously.

“It was our father who constantly encouraged us to play,” Ryuichiro(Ryoichiro) says. “We still can’t believe that even though we were born in a small town, we are now playing all over the world and popularizing the shamisen.”

Part of the Yoshida Brothers’ mission is to ensure the instrument I not forgotten by future generations. To this end, they are involved in a national program to reintroduce the shamisen to students all over Japan. Since 2001, middle schools up and down the country offer classes in traditional instruments as an optional course.

“Kids now have shamisen, taiko and koto lessons,” Kenichi says. “We went around Japan, visited many schools and showed the kids how wonderful and versatile the shamisen is. So many styles of music sound great on it, from flamenco to rock.”

Over the past five years, the Yoshida Brothers have also attempted to bring live shamisen performances to as many Japanese towns as they could.

“From 1999 till 2004 we toured Japan, averaging about 80 shows a year,” explains Tateno Kei(Kei Tateno), the Yoshida Brothers’ manager. “Now we spend about six months abroad and six months in Japan. Our hope is to familiarize people around the world with the beauty of the shamisen.”

The strategy seems to be working. Their debut album is selling extremely well in Japan, while music stores abroad are now starting to list the Yoshida Brothers’ album in their World Music section. Fans in Japan, meanwhile, can’t get enough of the pair. But the brothers are not content to sit on their laurels.

“Of course the shamisen represents Japanese traditional culture but our goal is to learn a lot about other countries’ music and folk traditions so we can merge them with our own,” Kenichi says.

“We often play in the US where people have never heard of the shamisen,” Ryuichiro(Ryoichiro) says. “Even so, they are really receptive to our music. Most young people come to our shows love our music but they are not necessarily into Japanese culture. We were shocked to learn that the shamisen is not even sold abroad. We looked for it in a big musical instrument shop in the US that had an amazing variety of treasures from many countries and yet it didn’t have a shamisen. We hope to change this.”

The brothers also dream of collaborating with musician Pat Metheny, believing they compliment his style, technique and power of expression well. “But we need a lot of improvement to play with him,” Kenichi adds, in a typical show of humility.

They are also impressed by Paco de Lucia, whom they saw live in Japan a few years back. “His fingers are so fast and precise that I know we are way behind him,” Ryuichiro (Ryoichiro) says. “But one day we would love to go and play flamenco with him in Spain.”

Knowing the pair’s gritty determination, long-term goals such as these don’t actually seem too far off in the distance. Keep your eyes peeled for a performance near you.

Story by Judit Kawaguchi

From J SELECT Magazine, October 2005

Recent Comments