You breathe in steam, the smell of soap. The water around you is so hot that it feels like it is melting through your skin, dissolving the knots in your calves and the tension in your shoulders. When you step out of the water, skin steaming, you are clean and utterly refreshed. This is the Japanese bath.

Bathing is an intrinsic part of Japanese culture. It marks the end to nearly every day, provides a social pivot for the family–much as the dinner table traditionally does in the west–and in many cases, the neighborhood. It also offers a focus for travel and sometimes promises a cure for disease.

The tradition and history of bathing in Japan is long and surprisingly convoluted for a country with so much hot water simply seeping out of the ground. Ritual purification, or misogi, has long existed in Shinto practices. Ancient myths tell of the god Izanagi-no-mikoto purifying himself with water after returning from the underworld. The first historical mentions of Japan from outside, in the Chinese text the History of the Kingdom of Wei, from about AD 297, tell of the strange, foreign customs of their island neighbors: “When a person dies, they prepare a single coffin… When the funeral is over, they go into the water to cleanse themselves in a bath of purification”.

Bath houses and hot water baths, however, came to Japan with Buddhism in the late 6th Century. Fundamental to the Vedic tradition which fostered Buddhism, temple complexes in India included an area for ritual bathing, and this tradition continued in Japanese Buddhism. Originally designed to be used by priests and monks exclusively, however, the Japanese soon opened these “yuya” to the sick. The spiritual and physical cleansing they provided rapidly gained popularity, and by the Kamakura Period (1185 to 1333), bath houses had become firmly established as part of Japanese culture. Nobles built private baths in their homes, and temple baths were opened to the general public–sick and healthy alike. As people gradually moved to the cities, public baths became increasingly popular, and in the Edo period the sento, or public bath, came into common use.

Following World War Two, the private bath became a status symbol, and, consequently the sentō fell into something of a decline. Despite this, they maintain a steady if not wild popularity, particularly with the elderly for whom the daily ritual of bathing is also a social focus of their day. Recently brought to vivid, if fantastical, life by animator Hayao Miyazaki’s “Spirited Away,” the sento still suggests a simpler, more innocent time in the popular Japanese imagination. From overseas, however, the sento has historically been both exoticised and eroticised. Though this scorn played a main part in the banning of mixed-sex bathing during the Meiji Restoration, both the exoticism and mixed bathing maintain a toe-hold, though the latter has long been relegated to remote parts of the interior.

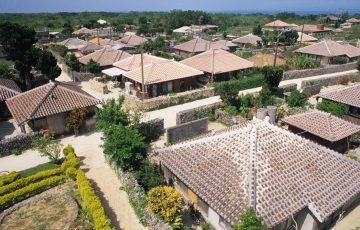

With geothermically heated water literally spurting from the rocks in some areas, it is surprising that hot springs bathing didn’t really become popular until the Heian Period (794 to 1185). A number of Japan’s most famous hot springs resorts, or onsen, have been in continuous use for over 1,000 years. Dogo Onsen in Shikoku, Arima Onsen in Kobe, and Shirahama Onsen in Wakayama Prefecture all date back to the 8th Century, and people still holiday here–amongst thousands of other onsen districts–to soak away the stresses of daily city life.

Though soaking in scaldingly hot water is therapeutic in and of itself, the mineral-rich hot springs waters are believed to cure a multitude of ills, from arthritis to depression and skin ailments to internal problems. Whether this is true or not, people taking toji (an intensive and prolonged regimen of multiple daily baths) swear by it. More often than not, however, hot springs these days are more tourist destination than health spa.

The public bath, whether sentoōor onsen is a place where social divisions are stripped off with clothes, a place of social levelling. There is even a term for this in Japanese “hadaka no tsukiai,” which loosely translates as naked togetherness or naked friendship. Visits to remote hot springs resorts, consequently, make popular company or club trips.

Flick on the television on any given night, and you’ll likely come across a travel program featuring one hot spring district or another, interspersed by commercials for body soap or shampoo which feature fathers bathing with their young children. It is obvious, even to a casual observer, that at home you bathe with your family; at the onsen you bathe with your friends or colleagues.

Bathing at home once followed a strict hierarchy, which, much like table manners in the west, has relaxed somewhat in the years post war. Where the father once bathed first in what may have been stunningly hot water, and the youngest daughter bathed last in the often tepid dregs, advancing technology now maintains water temperature so that any member of the family can bathe comfortably at any time of the evening. Bath time is now often a time of family communication, and busy fathers, in particular, treasure the time they spend bathing with their children.

Despite changing bathing practices across the centuries, the bath–whether onsen, sentō or private bath–remains centrally important to Japanese culture. Ultimately, bathing together, either with family or with colleagues, friends or neighbours, fulfils a social and cultural function, rather than simply a hygienic one, tying communities, groups, and generations.

Story by Skey Hohmann

From J SELECT Magazine, May 2009

Recent Comments