Geographically closer to Taiwan than mainland Okinawa, those who venture to Okinawa’s outer islands, the Yaeyamas, soon find out that this is the nearest thing to terra incognita they are likely to find in this country’s long and, apparently, not completely tamed archipelago. If Japan has a last frontier, it is here.

Okinawan music is now firmly in the world music catalogue.

The Yaeyamas, along with Okinawa’s better-known islands to the north, were incorporated into the Liu-chiu kingdom during its early 15th-century expansionist period. Under the later suzerainty of both the Satsuma domain of Kagoshima in southern Kyushu and as a vassal of China until 1872, the southern islands location in the South China Sea allowed it to assimilate both Chinese and Japanese influences simultaneously. These remote islanders have also been influenced by Southeast Asians drifting northwards on the warm currents of the Kuroshio – the black stream – allowing other, more exotic influences to creep in.

A combination of geographical isolation and the survival of robust traditions have helped resist efforts by Tokyo to remodel the islands and draw them into the cultural mainstream. Being out of the mainstream has benefited these islands in a number of other ways. The Yaeyamas were fortunate enough to be left comparatively unaffected by Japanese colonial policies of the last century and to have come out of the pitched battles of WW11, and the effects of the subsequent American Occupation relatively unscathed.

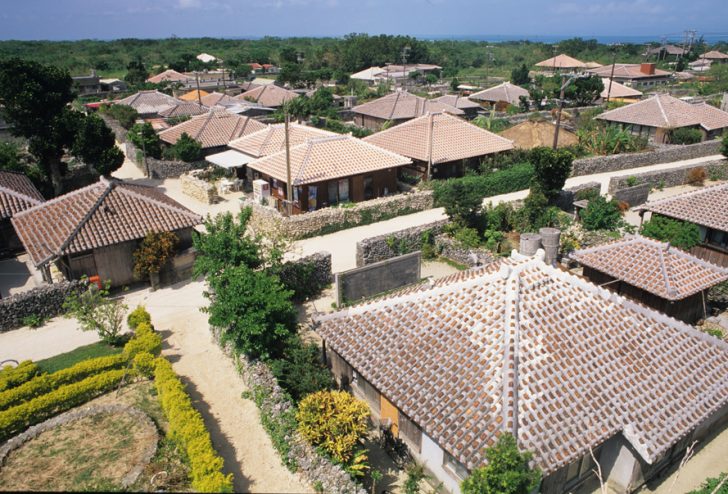

The name ‘Yaeyamas’ literally means ‘eight mountains,’ a name that, rightly, suggests the presence of large and highly visible rock deposits. The characteristically squat, heavily tiled houses of the Yaeyamas are made from volcanic rock, surrounded by stout palisade-like walls designed to protect the inhabitants against the potential havoc caused by the typhoon winds and rains that lash the islands in September and October.

A very green stonemasons’ yard in the village.

The climate, shifting dramatically between moderate and extreme, somehow manages to support surprisingly rich and variegated quantities of flora and fauna. Many of the islands are encircled by stunning coral reefs and its transparent waters are home to countless tropical species as well as more common shoals of game fish, lobsters, prawns and turtles. Extensive mangrove stands are common. Despite the craggy terrain, flora flourishes wherever it can. Hibiscus, a form of Chinese rose used – among other things – to decorate Buddhist altars and to beautify graves, is found in abundance here as it is throughout Okinawa. Camellias, bougainvillea, poinsettias and trumpet lilies spill in a carefully arranged riot from the walled lanes of villages, turning an ordinary stroll into a pleasant botanical encounter. Taketomi’s tropical blooms owe much to a relatively recent pipeline, which was built to carry water from nearby Ishigaki, replacing a precarious dependence on catchment water. Nature revived and flourishing is one of the delights of this island and a stroll around its sandy lanes hints at the pride these islanders have in their flora.

Nature resurfaces, subtly and abstractly manifested in the exquisite handiwork of the islanders, particularly their textiles. Southeast Asian techniques like stencil and tie-dyeing have lent strong influences. Indian style pencil-dyes can be seen and bought as well as samples of ikat, a textile technique strongly associated with Indonesia and other Southeast Asian countries. Bingata, a cotton and linen fabric soaked in natural pigments and vegetable dyes taken from wild plants, is the region’s best known textile. Covered in dazzling bird, flower, fan and shell motifs, a good piece of bingata can take a craftsman between two and three weeks to finish.

Shisha, mythological Okinawan lions and guardians of good fortune, are much in evidence in the Yaeyamas.

Many Okinawan fabrics that eventually find their way into shops and galleries from Naha to as far away as Tokyo, are produced by individuals or tiny co-operatives on remote islands few Japanese people ever visit. One such place is Taketomi, meaning “prosperous bamboo”, an island that can be reached in just 15 minutes by boat from the harbor on nearby Ishigaki

The Okinawan wall garden is a unique style in Japan.

Island. Taketomi is famous as the source of minsa, an indigo fabric often used as a belt for a women’s kimono. Minsa is only produced on Taketomi. Strips of the material can be seen drying on the stonewalls of the village. Taketomi has some of the best-preserved traditional houses in Okinawa, classic squat, red-roofed buildings with walls made from volcanic stone. Protective shisha lion statues placed on attractive red-tiled roofs, which resemble the tuilles roman of southern Europe.

A pleasant time capsule of sandy lanes, hibiscus and bougainvillea decked, one-storey houses squatting behind their characteristic storm-shelter walls, Taketomi boasts unspoilt beaches and its own thriving micro-culture. The population of Taketomi is only a little over 400. The island is barely nine kilometers in circumference, its main village easily negotiated on foot or by bicycle. Taketomi is best known for its star-shaped sand, the fossilized skeletons of diminutive sea animals, found along its western shore. Like all the Yaeyama Islands, Taketomi preserves a lively cultural calendar, which includes the observing of several unique festivals.

A typical old Okinawan-style roof, with bougainvillea growing in abundance.

Minsa belts are worn in the summer during the island’s unique Angama Festival. This version of Obon involves more than just the lugubrious visit of spirits to their former homes and burial sites. Two masked figures, representing a wizened but merry old man and a women, dance and gambol their way from one house to the next, engaging each occupant in a lively banter carried out in a local dialect that eludes most visitors.

From the broad sweep of Kondoi Misaki, a beach located along the southwestern shore of Taketomi Island, it is possible to see tantalizing glimpses of still more islands detached from the mainstream. On one of the most notable of these, Iriomote Island, a river meanders through a dense, partially unexplored jungle, and the sea is inhabited by manta rays that feed off its plankton-rich currents. Here, at the edge of Japan’s last frontier, spear-wielding fishermen cast small lights over the sea at night to catch fleshy lobsters and other fish along seashore that is a world away.

TRAVEL INFO

There are no hotels on Taketomi, but an overnight stay at one of its minshuku is highly recommended. The venerable Takana Ryokan (0980/85-2151) is an Okinawan inn of good repute which only charges ¥5,500 per night with meals. The even more affordable Minshuku Izumiya (0980/85-2250) is a friendly, plant-bedizened guesthouse located in the island’s one tiny village. There is usually an all-you-can-drink awamori (local alcohol made from Thai rice) option in most minshuku. The island is small, but renting a bicycle is a good way of circling the island, making sense of the village’s complex web of lanes, and getting down to its fabulous beaches. A quick visit to the small museum called the Kihoin Shushukan (9am-5pm) in the village provides an insight into island history, life and crafts. The visitor center (8am-5pm) by the port is another source of useful local information.

Story and Photographs by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, November 2010

Hosing down a water buffalo before the next set of passengers board for a tour of Taketomi’s flowering lanes.

Recent Comments