More than just a guy’s guy

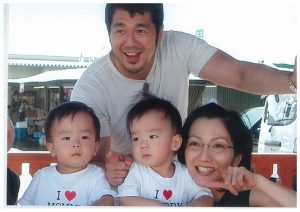

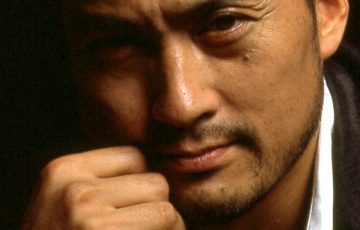

My 8-year-old daughter adores Nobuhiko Takada. To her, he is a giant teddy bear. In a tag game of kids versus adult, because of his lumbering 185cm, 95 kg, size he is the most obvious target and inevitably the first one tagged out. Indeed, when Reina and her friend add “Nobu-san” on their respective Nintendo DS Friends Collection game, Takada is categorized as the “cuddly, comforting” type.

My 8-year-old daughter adores Nobuhiko Takada. To her, he is a giant teddy bear. In a tag game of kids versus adult, because of his lumbering 185cm, 95 kg, size he is the most obvious target and inevitably the first one tagged out. Indeed, when Reina and her friend add “Nobu-san” on their respective Nintendo DS Friends Collection game, Takada is categorized as the “cuddly, comforting” type.

This image is a far cry from the Takada her father knows; “the hero of my student days and the most powerful man around.” My husband did not hesitate to spend his hard-earned pocket money hawking Bunmeido honey cakes to buy tickets and watch Takada battle in person. Perhaps it is precisely that Takada is genuinely both a teddy bear and a strong man that explains his success in the ring and his enduring popularity.

The Beginnings

As a young boy, Takada immersed himself in baseball. But at 14, he became enamored with the antics of the wrestler Antonio Inoki and changed sports. He says: “It’s hard to explain in words how charismatic Inoki was. He was a superhero in the flesh.” (Ironically, this would be the exact phrase my husband would use to describe his own admiration for Takada.) “It’s hard to imagine now but at that time, there were three regular, prime time pro-wrestling programs on television. One featuring Giant Baba, the other Inoki and the third had other wrestlers,” recalls Takada.

Professional wrestling in Japan began as mainstream entertainment. The small, taut Korean-born wrestler Rikidozan earned his status as a national hero in Japan by defeating huge foreigners. His 1963 victory against the American masked wrestler The Destroyer drew the largest television viewing audience ever in Japan’s history. Nearly all Japanese remember that moment. Most gathered at the home of some rich neighbor with a television set to cheer on Rikidozan. Baba and Inoki carried the torch into the 1970s. But in the 1980s, professional wrestling was relegated to a sport watched by a male-dominated audience.

Unlike baseball, there were no teams or coaches for professional wrestler wannabes, so young Takada trained by himself. “In wrestling magazines, they had sections showing how to do certain moves. I don’t think most readers took it seriously but I tried imitating everything I saw in the photos,” he says. “Also when I saw live matches, I would go early and see how the wrestlers warmed up.” What he didn’t do was engage in fantasy play by using sandbag opponents. “Sure, I did that as a kid, but that’s not training,” he comments. He trained seriously and by the time he was 17, Takada was selected to join Inoki’s club.

Takada’s rise in professional wrestling was a steady one. Debuting in 1981, for almost two decades he was one of the top fighters in a world where organizations fold and merge regularly. Takada chuckles and says, “I can’t even keep track.” What distinguished Takada from other fighters was his strength and victories. In addition, he was also a key figure of “shoot wrestling” – a more realistic style of fighting that eventually paved way for mixed martial arts.

“It was extremely frustrating for me that no matter how hard I trained and how many matches I won fairly, no one really believed it because pro wrestling always had an air of scripted drama. There were other strong fighters who felt the same way and fans who wanted to watch real fights, so the timing was ripe to move towards a more realistic fighting style,” he explains. Takada’s bouts against the top wrestlers of Japan’s other major wrestling organizations broke records again and again, drawing the biggest crowds at that time.

So what does “strength” actually mean to someone who has personified that word? And what does being “a man” mean to someone so idolized by men? For someone who has been the definition of both, his answer is curious. “To have the ability to pick yourself up after failure,” he says after some contemplation. “That is the strongest thing a man can do,” he replied. And losing is also something Takada knows about.

Fighting for Pride

Pride Fighting Championship began in 1997 as a simple concept. It would pit Nobuhiko Takada — the star of Japan’s fighting world — against Rickson Gracie, the legendary Brazilian wrestler. The other matches were fillers to this “best of the best in the world” fight. It was a greatly anticipated match-up heavily covered by Japanese media. People expected it to be the Heisei version of Rikidozan proving to the world how powerful Japan was. “And I lose, in a big way. In a humiliating way,” Takada says. He does not sugarcoat his words. “For over a month afterwards, all I felt like doing was crying,” he admits. “I didn’t want to retire yet but could not imagine myself returning to the ring after such a defeat.”

But Takada was given a chance for redemption. The promoters said that despite the loss, people felt he deserved a rematch. Rickson Gracie could have had his pick of opponents but to Takada’s surprise, accepted the challenge. “I feel Takada is a warrior and deserves the chance to try and redeem himself,” Rickson explained in a 1998 magazine interview.

“The first time around, I took the fight too seriously. I changed my entire style of training. For one year before the match, I stopped drinking alcohol and for the first time in my life, I controlled my weight. I let the pressure of the fight change that the fighter I was instead of practicing what I had always believed in. But the second time, I did things my way, did what worked for me in the past. Yes, I did lose that match as well. But it was one where I fought to the best of my ability and lost in a way that I could walk away with pride,” he explains. “My initial loss paved way to lots of great things. When you win, it feels great. But I learned that even good things can come from a loss and you learn more.”

Because of the rematch, what was intended to be a one-time event won by Takada, led to many more Pride tournaments, pitting reputed fighters from all over the world against Japan’s best in a mixed martial extravaganza. In its 10-year run, Pride Fighting Championship enjoyed immense popularity worldwide, broadcasting in over 40 countries. Pride ended in 2007 when the owners of America’s Ultimate Fighting Championship bought it out and brought the organization’s best fighters into their organization. Although Takada was past his prime during most of the Pride events, he was proud to have been an integral part of what became a quest to crown the strongest fighter in the world.

Celebrity career

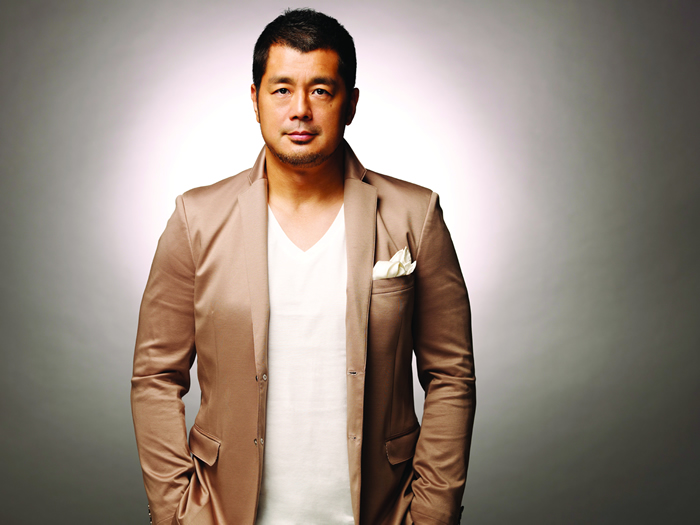

Professional wrestling is both a sport and entertainment. While Takada gradually retreated from the top ranks of being an athletic fighter, he continued as a “show wrestler.” In 2004, Takada swung to the opposite pendulum of the wrestling world and started Hustle, an organization high on theatrics and low on skills. As Generalissimo Takada, the main heel character, he still drew in an audience. With his 2009 departure, the organization soon folded.

During this time, Takada also took on other types of work as an entertainer, including doing a Japanese voiceover for the villain in the Pixar film “The Incredibles.” “I just remember having to growl a lot, really loudly,” he remembers. While many retired athletes make their way to television shows upon retirement, they fade away after a year or two. But even now, there is not a week that goes by without seeing Takada on some variety show, be it a quiz game or a travel program. He is even asked to be a commentator on music programs.

His popularity comes from the two different sides of his personality. To women and children, he is a giant with a soft voice, a gentle demeanor and a boyish grin. To men, he is still the alpha male, always strong, often a leader. When they see him make self-depreciating jokes, he becomes “one of the guys.” The other factor is the professionalism with which he approaches work. “There are obviously projects I enjoy more than others but every time I take on an assignment, I hope to get at least one “hit.” By that, I mean whether I have done a good job making amusing comments or made my presence known.”

Educating kids

The type of work he enjoys the most is educational ones. While his Takada Dojo is best known in the fighting world as producing Kazushi Sakuraba, one of the greatest mixed martial artists ever, training top fighters is not actually a priority for Takada. “Instead of teaching a small elite group, I am more interested in reaching out to more people and getting them to move their bodies physically,” he explains.

Takada Dojo offers many wrestling classes for the general public, especially children. They even have gymnastic classes to develop overall coordination. “Parents bring their kids here wanting them to learn discipline and endurance. I want to instill those values, but to do so, I have to also make it fun for kids,” he explains. What points to the success of the Takada’s program is the low drop out rate. “Once they start, the kids stay for a long time,” he says proudly.

In order to encourage even more kids to play physically, he started his Diamond Kids College program, a free workshop for kids from 4 to 12 held all over Japan every month. Although it is technically a “wrestling class,” Takada is not interested in scouting the next big thing. By watching their children have fun through games and activities, Takada wants to reach out to parents and encourage them to take their kids outdoors to play, run and explore. “Kids have to run and fall, get physically hurt and then pick themselves up. They have to get hit and realize how it’s painful so they don’t hit others. They have to push themselves in games, experience the thrill of winning and learn from their defeats,” he explains. “When people ask how I became the way I am, it’s because of these simple things which unfortunately are becoming rarer now, ” he says.

As a parent to seven-year-old twin boys, Takada knows personally how hard it is steer city kids away from video games. He recalls seeing the changes in his sons during a trip to Yakushima Island. “At first, my boys were too scared to climb up high and were squeamish about everything. But when they met an older local boy who showed them how to collect water bugs or prowl through jagged rocks, they got so excited at taking on new challenges. I believe children need to do that to grow strong,” he says.

So last year, he took on a new project called Nobuhiko Takada’s Nature School. Consisting of three weekends throughout the year, the program centered on rice planting, harvesting and threshing. Each weekend also included other agricultural activities, from digging up vegetables to collecting eggs and milking cows. A weekend with a celebrity would usually come with a hefty price tag, but the trip is much cheaper than other tours because Takada uses his fame to get people to contribute. The rice field, the vegetables and the knowledge of growing rice are all free. At a Diamond College workshop, there are special guests such as Olympic gold medalist Sayuri Yoshida and former sumo yokozuna Akebono. Again, they donate their time out of respect for Takada and his cause.

Indeed, the respect Takada commands is widespread, but he strives for more than public recognition. “When my sons get to the age when they wander rather than have a direction, I’d like one say to the other, ‘Hey, you better not do that because if dad finds out, you’re going to be REAL sorry.’ That’s the kind of authority I’d like to have earned. That’s finally when I would consider myself a man.”

Recent Comments