In 1965, the Dutch anthropologist Cornelius Ouwehand and his wife Shizuko, sailed to the remote Okinawan island of Hateruma to undertake research. The series of monochrome images they took of daily life, work and ritual on the island were eventually published under the simple title, ‘Hateruma.’ Their journey to the island in a small craft from Ishigaki port would have taken four to five hours.

In 1965, the Dutch anthropologist Cornelius Ouwehand and his wife Shizuko, sailed to the remote Okinawan island of Hateruma to undertake research. The series of monochrome images they took of daily life, work and ritual on the island were eventually published under the simple title, ‘Hateruma.’ Their journey to the island in a small craft from Ishigaki port would have taken four to five hours.

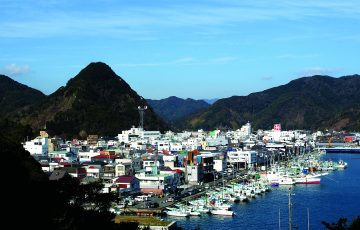

Today’s crossing, in a battered looking but decidedly faster ferry, takes slightly under one-hour. It can still be a rough journey. In my case, the sea was initially as calm as a pond, but grew choppy once out of the harbor, waves slamming the small boat with sickening thuds, spray obscuring any view of the presumably blue seas.

If he were alive today, Ouwehand might be surprised by the handful of small minshuku, the island’s two or three drink vending machines, tiny airstrip, bicycle rentals, intrepid divers, and wind turbine, but little else. In essence the island has changed little, though you would have to spend a long time on the island to know how many of its customs are still observed. In Ouwehand’s book we see female priestesses conducting rituals before prayer rocks, inside caves and at the center of sacred groves. Here we see prayers for clement weather, wells, the bottom of the sea. One large prayer stone has scorch marks where fires were burned on top of the rock, a custom marking the birth of a baby to a family. Women, who enter the sacred sites barefoot, are the spiritual transmitters, with men playing a limited, rather marginal role.

Are such rituals still maintained? It seems likely that some are, that others have survived in modified form. Its unlikely that a goats head and four feet, tied with ropes and weighed down with stones, are sent out to sea on barges as offerings to the gods, but in the preface to Ouwehand’s book, a journalist visiting the island as late as the 1990s, tells of receiving a sharp reprimand from a local when he tried to approach the entrance to a pitenua, an Okinawan word denoting three sacred spots located at the heart of vegetable fields. Seeds and animal offerings were made here by priestesses, the sole people allowed to enter the center of the site.

Some dilution of culture since the 1960s was inevitable. Even in Ouwehand’s photos, we see a striking contrast between the traditional textiles worn by older women, with their Okinawan motifs, and the Western clothes and hairstyles of the younger islanders. The book tells of a woman in some distant, unspecified time, who places a stone phallus on the shore, in the hope that it will facilitate a safe voyage for her husband. The woman’s name, Yamadabupame, seems to hail from a marine world far beyond Japan. By Ouwehand and Shizuko’s day, the woman’s descendants go by the family name Yamada, a simplification into a common Japanese name. The Polynesian or Melanesian tints have been leached out a long time ago.

There are few temples in these out islands. On Hateruma there are none. Shrines, with their closer ties to the animist world are more common. Despite obvious parallels in social organization and linguistic ties with mainland Japan, a combination of geographical isolation and the survival of robust traditions have helped these islands resist outside influences. Commenting on the limits of Japanese acculturation in the region, William Lebra notes in his book, Okinawan Religion, “there has been an ebb and flow of contacts through the centuries, not a continuous and unilateral interaction.” It’s an important difference.

Although there is not a great deal to do at the level of conventional tourism, you don’t have to be an ethnologist to enjoy Hateruma. For visitors who appreciate nature and the pleasantly retarded pace of life in distant parts, there is much to recommend an island with no hotels, tour groups, swanky restaurants or cafes. Its healing beauty comes as quite a surprise. The waters of small Japanese ports tend to be covered with a film of oil, levees hung with greasy ropes and rusting machinery. Even the beaches of mainland Okinawa are beginning to see a daily overspill of small-scale industrial and medical garbage from continental China. Hateruma’s waters remain transparent, with a rich diversity of coral clearly visible beneath waters of four or five different tones of blue.

Although there is not a great deal to do at the level of conventional tourism, you don’t have to be an ethnologist to enjoy Hateruma. For visitors who appreciate nature and the pleasantly retarded pace of life in distant parts, there is much to recommend an island with no hotels, tour groups, swanky restaurants or cafes. Its healing beauty comes as quite a surprise. The waters of small Japanese ports tend to be covered with a film of oil, levees hung with greasy ropes and rusting machinery. Even the beaches of mainland Okinawa are beginning to see a daily overspill of small-scale industrial and medical garbage from continental China. Hateruma’s waters remain transparent, with a rich diversity of coral clearly visible beneath waters of four or five different tones of blue.

Unlike mainland Okinawa, Hateruma, the southernmost island in Japan and part of the far flung Yaeyama chain, remained largely outside of the ring of fire during the war. There were other dangers in those days, though. A memorial located in the Haemi area of Iriomote-jima, a larger island in the same chain, bears the inscription, “Stone of not forgetting.” This is a memorial to the 461 students who perished from malaria during WWII. The principal of the Hateruma Citizen’s School, wrote the calligraphy inscribed on the stone, telling how, towards the end of WWII the imperial army forcibly evacuated the students here, where the dire conditions led to their deaths.

There are probably more obviously beautiful islands in this chain, if beauty means manicured homes, elegant craft shops and exhibition gardens. Hateruma is undeniably beautiful, but it is a weathered, more rustic beauty, one that derives from use, wear and tear. The walls of its old wooden houses are wind battered and salt-eaten, roof tiles eroded by rain and humidity. The people themselves seem more crusty, their skin dark and leathery.

The best way to see the island is to provision yourself with a sun hat and plenty of water and then rent a bicycle. Although it can be a hot ride, the island is largely flat, and at 6km in length, 3km at its widest, its empty, well-made main roads and earth lanes are easily negotiated. The name ‘Hateruma’ means “the end of the coral,” a reference to its southern location. “Beyond here,” local maps tell you, “the Philippines.” Nihon Sainantan, a cement memorial, sitting on a buff above a rocky cliff, marks the spot as the nation’s Southernmost Point Monument.

Cycling allows you to take in the minutiae, starting with the village itself, situated like most settlements in small Okinawan islands, right in the protective center of the island. Besides the old houses, some painted in limes and faded blues, it is the flora that you notice. Yellow and red hibiscus spilling over coral walls, trellises of bougainvillea, backyard plumerias, banyan trees, bamboo orchids and, outside the margins of the village, the sea-facing pandanus, Indian almond trees, and fukugi. Divers discover an even more colorful undersea world of honeycombed coral, caves, hollows, and fish like rainbow runners, red fin fusilier and the strangely named Moorish idol.

Some of this fish finds its way onto the dinner table of Hateruma’s guesthouses. The food at the minshuku I stayed was simple, healthy and bounteous. So was the local firewater, called awanami. Bottles were placed on a side table alongside buckets of ice. Guests simply helped themselves to as much as they liked. At over 25% alcohol content, I took it easy the first night. The drink is Hateruma’s version of Okinawan awamori, a drink made from Thai rice, hinting at old trade routes and cultural links between the islands and Southeast Asia. I was lucky to be tasting it at all. Locals have a nose for the stuff. When a fresh batch is ready, locals rush to the island’s single brewery, a tiny affair on the periphery of the village, and buy up all the stock.

It goes down very well with Okinawan dishes. Although the more exotic snake meat dishes and Okinawan favorites like julienned pork ear served with cucumber and dressed with vinegar, were absent from the meals here, I enjoyed goya-champuru, the bitter melon preparations, pickles marinated in brown sugar, goat stew, fresh fish, and the passion fruit, mango, papaya, banana, custard apple and dragon fruit I’d seen growing in private kitchen gardens in the village.

Part of the joy of traveling among the rural communities of islands like this are the encounters with elders, sprightly folk who embody the Okinawan concept of nuchi gusui, the healing power of food. The expression recalls the words of Dr. Tokashiki Tsuka, a physician to the King of the Ryukyus, who wrote in his 1832 Textbook of Herbal Medicine, “If we nourish the spirit through proper food and drink, illness will cure itself.” Its often a very real surprise to come across an elderly person working in the pineapple or sugarcane fields, apparently carrying sizeable loads, who turns out to be in his or her nineties. A staggering, disproportionately high number of the world’s super centenarians in fact, live in these islands. As Okinawans have no particular predisposition to longevity, the reasons are assumed to be a combination of diet, regular exercise and low stress lifestyles.

A degree of self-discipline, of course, is required to follow the Okinawan way. The expression hara hachi bu, is often invoked in Okinawa, meaning something like “leave a little bit of room in your stomach after a meal”. The saying reminded me of the comment made at the ripe old age of ninety, by the Okinawan karate master Gichin Funakoshi: “I eat sparingly, never to the point of being full. Vegetables are a favorite item in my diet, and although I am fond of meat and fish I eat both with restraint.”

A degree of self-discipline, of course, is required to follow the Okinawan way. The expression hara hachi bu, is often invoked in Okinawa, meaning something like “leave a little bit of room in your stomach after a meal”. The saying reminded me of the comment made at the ripe old age of ninety, by the Okinawan karate master Gichin Funakoshi: “I eat sparingly, never to the point of being full. Vegetables are a favorite item in my diet, and although I am fond of meat and fish I eat both with restraint.”

Its advice that is easy to digest when you are in a place like Hateruma, where everything conspires towards good health and a feeling of being thoroughly cleansed and restored. A little bit more difficult to adhere to at home.

TRAVEL INFORMATION

Ferry tickets to Hateruma can be bought from inside Ishigaki Islands new port terminus. There are four ferry departures a day from Ishigaki port on the Anei Kanko and Hateruma Kaiun lines. The journey takes about 50 minutes. Ryukyu Air Commuter has one 20-minute daily flight from Ishigaki aboard a nine-seater Islander aircraft. In good weather the views from the small, low-flying planes are superb. At present, there are only minshuku on the island. Nishihama-so (0980-85-8290) is a budget one with kitchen facilities and free rice. Tamashiro (09808-5-8523) is excellent value with huge dinner servings. Shuttle cars to and from the port are provided by the minshuku. Just west of the village, directly south of the port, Pananufa is a charming restaurant-café with a small library and musical instruments to play. There are three or four bicycle rental shops on Hateruma, each charging around ¥1,500 a day. They will provide you with a useful hand drawn map of the island. Cornelius Ouwehand’s photo book, Hateruma, with a short text and captions in Japanese, is available in the bookshop in the shopping arcade on Ishigaki Island.

Story & photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, September 2008

Recent Comments