It’s probably safe to assume Kaname Matsumoto had not seen the 1989 flick Field of Dreams when he nailed together his first wooden structures on the dusty parking lot of his refrigeration warehouse 16 years ago. Nevertheless, the energetic 64-year-old had decided to adopt a very similar mantra to the one followed by Kevin Costner’s lead character in the Hollywood classic Ð if you build it, they will come.

It’s probably safe to assume Kaname Matsumoto had not seen the 1989 flick Field of Dreams when he nailed together his first wooden structures on the dusty parking lot of his refrigeration warehouse 16 years ago. Nevertheless, the energetic 64-year-old had decided to adopt a very similar mantra to the one followed by Kevin Costner’s lead character in the Hollywood classic Ð if you build it, they will come.

But instead of constructing a baseball stadium, Matsumoto unveiled a more straightforward plan in order to help his hometown of Kushikino realize the importance of maguro (tuna) to its cultural heritage: he inaugurated the first ever Kushikino Maguro Festival.

With a mere eight booths, a few hundred locals came during the first festival to examine the products on display. In 2005, the same festival would draw in more than 105,000 in attendance Ð making it the largest public event in Kagoshima prefecture that year. Nevertheless, the festival was cancelled altogether last year owing to a lack of funding. But absence does indeed make the heart grow fonder, and the community, the local government and the town’s maguro association rallied together this year to revive it.

“A festival shouldn’t be the effort of a single person,” Matsumoto says with a smile. “Finally the town realizes its identity as a maguro town.”

With weathered skin, a taut body and a twinkle in his eyes, Matsumoto is a hyperactive character. On the day before the festival, he trots around the site twirling hammers, electric screwdrivers and paintbrushes, fixing sets and barking orders. Although he has officially stepped down as festival director, it’s easy to tell who is still in charge.

After 22 years of working his way up the ranks to take the helm of a fleet of maguro longliners, Matsumoto returned to land to head a subsidiary of the maguro company his father created. Back in Kushikino, he was dismayed to find that the city had no identity with the product that had historically fueled its livelihood.

“At one time, Kushikino was only second to Kesuguma in Miyagi prefecture as a maguro port,” he says. “Even today, Kushikino’s 68 maguro longliners deliver the maguro served on dining tables all over Japan. Maguro fishing revenue brings in approximately ´30 billion per annum to the city. Yet nobody knows this because the maguro from our vessels are not delivered here but dropped off in ports closer to Tsukiji Market.

“Now more than two-thirds of the crew on the longliners from Kushikino are non-Japanese. The men running maguro companies went to college instead of the school of hard knots. Maguro fishing culture was disappearing from Kushikino. Something important would be lost without people knowing it.”

Kushikino is quite the party town, hosting almost 10 public events a year. Thus for the first 10 years, the festival was just another matsuri in the crowd. But Matsumoto poured his heart and soul into the Maguro Festival and, as a result, it soon stood out from other annual festivals that were organized in the town.

Kushikino is quite the party town, hosting almost 10 public events a year. Thus for the first 10 years, the festival was just another matsuri in the crowd. But Matsumoto poured his heart and soul into the Maguro Festival and, as a result, it soon stood out from other annual festivals that were organized in the town.

Budget-wise, a festival this size could not call on a big-name entertainer but this was Matsumoto’s show and he splurged company expenses to invite Ichiro Toba, a popular enka (country music) singer, to make an appearance. A former tuna longliner fisherman himself, Toba has a huge following in fishing communities. Fans from neighboring towns drove in, creating traffic backlogs that were unusual in that part of southern Kyushu. Bus loads of Toba fans from as far as Mie prefecture attended this county fair. The popularity of the fair grew steadily but it was not until the 10th festival Ð and the introduction of the Kushikino maguro ramen Ð that the town really began to identify itself as a maguro town.

Yoshikatsu Ueebisu, head of the Kushikino Tourism Association, explains how they had wanted an original local product.

“The city of Kurume is nationally famous for its tonkotsu pork soup ramen so we thought that ramen would be a good product to try,” he says. “The town’s restaurant owners experimented, and over one year they developed a maguro soup that was rich in flavor, yet did not have a fishy aftertaste. Seasoned maguro sashimi was selected as the special topping.”

When this product debuted at the 10th Maguro Festival attended by tens of thousands of Toba fans, it drew national attention. Featured on television, in popular magazines and gourmet mangas, the ramen fulfilled Matsumoto’s dream of stamping Kushikino’s association with maguro forever.

“Look, there’s another poster,” Matsumoto points out as he drives around town seeing small shops displaying Maguro Festival posters. “When I think about how far the festival has come, I feel like a proud father.”

In town now, people buy maguro directly from local companies rather than buy sashimi from supermarkets via Tsukiji Market. There are eight restaurants in town serving maguro ramen. The town’s swankiest hotel, the Seaside Garden, features a maguro lunch buffet with deep-fried maguro chunks, seasoned sashimi and stewed organs Ð a ´980 feast that would certainly cost over twice as much elsewhere.

By its 15th incarnation in 2005, the Maguro Festival had become a local staple. Yet despite its record-setting attendance, it was not held at all the following year. While the local government doled out ´1 million for the event, about ´3 million came from Matsumoto’s company budget. Worldwide fishing restrictions of the southern bluefin tuna, the mainstay of Matsumoto’s company, drastically tightened the purse strings and his company could not financially commit.

Good things are sometimes taken for granted. Kushikino missed the Maguro Festival almost as soon as people found out it would not be held. In a small town, word-of-mouth opinion matters and the local government felt strong pressure to revive it. Thus, the local government contribution to the event increased to ´3 million for this year. The rest was expected to come from the association of 15 local maguro companies, who would be responsible for its organization.

The festival this year did not have the funding to call on Ichiro Toba. Instead, the main drawing card was local hero Makoto Nagano, a commercial mackerel fisherman. Nagano is famous for being only the second man to complete a rigorous televised obstacle course. With a dashing smile and a warm personality, he has garnered fans of all ages. Neither a professional athlete nor entertainer, it is rare occasion to meet Nagano who spends 25 days of every month at sea.

The festival this year did not have the funding to call on Ichiro Toba. Instead, the main drawing card was local hero Makoto Nagano, a commercial mackerel fisherman. Nagano is famous for being only the second man to complete a rigorous televised obstacle course. With a dashing smile and a warm personality, he has garnered fans of all ages. Neither a professional athlete nor entertainer, it is rare occasion to meet Nagano who spends 25 days of every month at sea.

Some visitors went to extraordinary lengths in order to meet the fisherman. Naoko Kubota and her friends took an overnight bus from Fukuoka to get him to sign their baseball caps. Hideki Komaki and his young family drove for more than four hours to attend the event. Another huge Nagano fan, he worked out to reduce his body fat to replicate Nagano’s reported 5.4 percent.

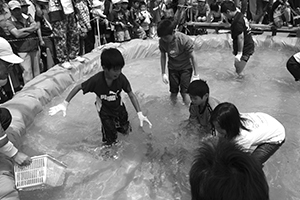

Other highlights of the 2007 festival included demonstrations of frozen maguro slabs being electrically chain-sawed, a tour of a coastal guard ship and kids catching fresh fish with their bare hands. The main door prize was a whole frozen maguro Ð valued at around ´100,000. Even with its new foster parents, the festival exceeded expected attendance and products sales.

Matsumoto gave the town an identity long before it realized it needed one. The Maguro Festival has put Kushikino in the spotlight and drawn attention to the town and its wealth of resources. The time has now come for the town to repay the favor.

Story by Carol Hui

From J SELECT Magazine, August 2007

Recent Comments