Mari Mari, quite contrary, how does your Japanese garden grow?

With large flat stones and no garden gnomes, and temple tiles all in a row, writes Stephen Mansfield.

Having accumulated a small library of books and magazines devoted to the subject of Japanese gardens as well as having visited more than 150 gardens stretching from northern Honshu to Okinawa, I would have thought my experiences would have left me in good stead for making a garden myself.

As I discovered, however, no amount of observation or theory can completely prepare the novice green thumb for the practicalities of design and implementation needed to see such a project through to fruition. What follows, then, are the observations of a determined but flawed amateur, a description of the steps involved in making one particular garden so that you have a clearer understanding of what is involved.

Having pottered around for a long time with temporary gardens attached to rental properties, we bought our own house in May 2005. By urban standards the plot at 66 tsubo (207.8 meters) was generously proportioned, the house taking up roughly half of the land. While wooden slated walls or the beige of suna-kabe (sand walls) would have been ideal, the surfaces of the house were off-white, a good enough color to work against, as its neutrality is none intrusive.

The former owner of the house, a cheerful widow in her sixties, had been a garden lover and there was much to commend in her scheme of things from the perspective and tastes of a certain generation of Japanese middle-class householders. Garden tastes and aesthetics, though, are nothing if not personal. The more I looked, the more I wanted to eliminate, to superimpose a different design, one that would be conspicuously Japanese, but suited to the modest aspirations of a suburban garden. When I thought about the kind of garden I would like to have, a line from Masaaki Tachihara’s Wind and Stone, a novel ingeniously crafted around the construction of a private landscape design, came to mind: “It was not an extravagant garden, but it had elegance and good taste.”

In making a garden, the first inclination is to rush, to try and complete everything in one season. A professional, having a complete garden template in mind, might be able to manage that, but for the amateur, a slow and sometimes costly process of trial and error is inevitable. Patience, if you have it, is a highly practical virtue when making a garden.

In choosing materials, Japanese do-it-yourself type stores and garden centers these days are catering more and more to homeowners keen on creating an “English garden.” As an Englishman, I could see the irony here. The results are often similar to gardeners in the United Kingdom who set out to built Japanese gardens but ultimately end up mixing plum trees, stone lanterns and pump-operated waterfalls with a liberal throng of garden gnomes, flower baskets and cement wheelbarrows. At least my circumstances – living in Japan – if not my nationality and background, were on my side.

In choosing materials, Japanese do-it-yourself type stores and garden centers these days are catering more and more to homeowners keen on creating an “English garden.” As an Englishman, I could see the irony here. The results are often similar to gardeners in the United Kingdom who set out to built Japanese gardens but ultimately end up mixing plum trees, stone lanterns and pump-operated waterfalls with a liberal throng of garden gnomes, flower baskets and cement wheelbarrows. At least my circumstances – living in Japan – if not my nationality and background, were on my side.

The cardinal rule from the outset when making a Japanese garden is that it should contain no artificial materials such as concrete or plastic. That meant removing, or at least concealing, the metal fencing that acted as the basic garden periphery; several rows of cement logs and a plastic garden table would also have to go.

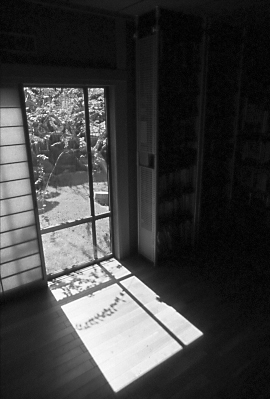

There was something about the choice of certain stones by the former owner, towards which I developed an intense, irrational dislike. Two in particular, often referred to as kushi-nuki-ishi (shoe-removing stones), looked as if they would have to go. These are the large, flat stones that can be found underneath sliding doors and windows leading on to gardens, or at the entrances of more traditional residences, and are, as the name suggests, for taking off shoes or sandals. Most houses are content to have one.

The stones, from Gunma and Gifu prefectures, had been cut and then polished on their top surfaces, giving them to my mind a flashy, lapidary effect. One was a chlorite schist stone (ao ishi) of a kind that is inexpensive, plentiful and indistinct. Another was a shiny, liver-colored slab. The third though, dark jade in hue and looking like a sheet of moss when wet, was of such fine quality and proportions, that I decided to keep it. What I hoped to find as a replacement for the stone beneath the kitchen door was a darker, more subdued rock, of the type sometimes observed in dry landscape gardens or among the half-lit shrubbery of the tea garden, one that would be in keeping with the overall effect I was trying to create.

Good stones can be very costly, running into millions of yen. One thing worth knowing about replacing stones is that gardeners are sometimes willing to do an exchange. To remove the two stones I didn’t need and find one replacement, I would need the services of a professional gardener. As stones are often the foundation of any landscape design – the skeleton of a garden, so to speak – it was necessary to attend to them first. This is especially advisable if the stones you are dealing with are quite large and need to be dragged across the surface of a garden, or if heavy equipment needs to be introduced. Bearing in mind the kind of damage that could be caused in circumstances like this, I decided to address the placement of more perishable things like plants and lawn after the stone settings were completed.

This was just as well, for removing the center stone along the outside wall of the living room and repositioning the green stone closer to the library window required a mechanical pulley system of the traditional type and a good deal of physical effort, as stones were literally pushed over logs towards the gardener’s truck. The work required three tough men, all seasoned garden workers in their sixties. Still unable to find a replacement, the stone under the kitchen windows has remained.

Bamboo fencing can add an elegant and naturalistic touch to a Japanese garden. Easy to maintain, cheap and unquestionably durable, plastic is now very popular, but pales against the real thing. After spending long hours going through various books and catalogues, a two-meter-wide bamboo fence was chosen. The bamboo was ordered from a supplier in Kyoto, the fence constructed on site after the wood was scrubbed and treated against insect invasion.

Fences are part of the revealing and concealing process, which is an important concept in Japanese gardening. Depending upon your immediate environment, you will either want to ‘borrow’ a view, so that yours is enhanced or expanded through the optical illusion of enlargement by association, or you will wish to conceal something. In the case of Japanese urban homes, the latter is most likely.

In our case, the left-side prospect viewed from the rooms at the back of the house was reasonably complimentary to the proposed garden: a Japanese style house, replete with ceramic tile roofing. A minor irritant was the side of the neighbor’s rusty shed. The main eyesore, though, was the main neighbor’s house at the back, where sections of the their garden were used for storing trashcans, ladders and a revolving washing line.

The bamboo fence had already succeeded in masking off the washing stand; the answer for the remaining borders seemed to be in a wall of nicely trimmed bushes. Eleven maki (podocarps), a darkish green tree common to traditional Japanese gardens, were ordered and planted. The half-meter space between each plant, it seemed, would take roughly four years to fill out. In order to speed up the process, another 10 maki were ordered and planted in early spring of this year. These will provide more privacy and help to create more mass within the garden.

Most of the original garden was covered in a gray sand not unlike industrial road gravel. This would be replaced with turf. Grass may seem antithetical to the Japanese garden, but it has been popular in certain types of gardens – such as the kaiyushiki-teien (stroll garden) – since the late Edo period. You can buy evergreen turf here, but most Japanese gardens use a variety that turns into the color of barley by late autumn. By April, a gradual greening takes place, reminding you of the seasons and the passage of time. I ordered 400 pieces of turf, which would allow some spares to be cut into smaller sizes to fill in the borders and irregular spaces around the path and rock formations. Although this is fairly labor intensive – you should soften up the earth before laying turf – the process itself is straightforward enough and very rewarding, as you see a large section of garden quickly transformed.

When turf is laid, the pieces should not touch. The final effect looks a bit like a chessboard. Grass grows rapidly here from the spring onwards, requiring a cut every 10-14 days. The lawn should be watered roughly every three days when there’s no rain, the earth lines between the turf saturated like a puddle.

After the first cut, I put shibafu hirio, a fertilizer, over the grass, something that should be repeated every year. Seeing little growth between the turf, I bought two bags of mezuchi, a loose earth mix, for filling in the gaps in the hope that the turf would join up. It looks like it will take a second summer for the lines between the rectangles to grow over.

Perhaps the most difficult part of creating something approaching an authentic Japanese garden is in making a new design look like an old one. Japan’s humid summers help to accelerate the process, and a young garden can begin to look nicely weathered in a relatively short space of time.

I was able to aid this process by planting clumps of moss in the earth and stimulating the appearance of both moss and lichen on stones by regularly watering them. In addition, I smeared natural yogurt over the stones’ surfaces on the odd dry days during the rainy season, which is supposed to be a good way to stimulate bacterial growth.

I was able to aid this process by planting clumps of moss in the earth and stimulating the appearance of both moss and lichen on stones by regularly watering them. In addition, I smeared natural yogurt over the stones’ surfaces on the odd dry days during the rainy season, which is supposed to be a good way to stimulate bacterial growth.

Wanting to keep the garden simple but lush with greenery of different hues that would contrast with dark or mossy stones, I eschewed decorative touches such as stone lanterns, waterfalls, and water lavers. There were two additions, though, which I felt would enhance the aging of the garden. The originators of the Japanese tea garden introduced the idea of placing objects in a new context that would give them and the garden a fresh dynamism, but also link them to something older.

This idea, known as mitate, is seen in the use of recycled temple pillar stones, millstones taken from old buildings, temple tiles and roof pediments. Ishi usu, round, flat-surfaced stones with blunt, serrated radials on the surface, were often used on farms as kitchen boards to wash, prepare and cut vegetables. These have now found their way into gardens as ornaments, accents in an otherwise flat surface of sand.

The gardener who helped dispose and realign the heavy stones for us, managed to find two ishi usu for me from an old farmhouse in Chiba prefecture. Counting the number of generations back, the stones were dated from the late Meiji era. An old house that was about to be demolished, provided enough gray tiles (kawara) to build a border around the house that would later be filled in with small black stones to form what is known as an inu-bashiru.

Among the small trees bought for the garden were pine, juniper, sarusuberi, dwarf maple, azalea, nezumimochi and fragrant olive, while plantings included fern, fatsia, cycads and tamaryu. Any plants that were deemed unsuitable were either given away or transplanted to a strip of earth running along the road in front of the house, where there are azaleas and willow trees.

Making a garden is a never-ending learning process. This summer I hope to do my own pruning, including the tricky pine tree, plant more low level shrubs, build a low stone wall planted with ferns or trailing grass clumps beneath the bamboo fence, and learn a bit more about garden maintenance in general.

At the time of writing, I still haven’t found that replacement shoe-removing stone beneath the kitchen window, which will decide the depth of the border along the back of the house. That means that this space cannot be filled in with the black pebbles still sitting in their packets; nor can the gray roof tiles be sunk into the earth as borders, or the alignments of the two round ishi-usu be precisely set. And whether natural yogurt smeared over rocks during the humid summer months really help to propagate moss and lichen patches, as one garden source recommended, remains to be seen.

The garden, then, is still incomplete but as I have discovered over the past four seasons, the ultimate joy of a garden is that, once started, it is never entirely finished.

ESTIMATED CostS

Depending on size and design, anyone wishing to make their own garden should be able to do so at considerable less expense than the costs listed here. The following may seem expensive, but this was based on the purchasing of a fairly large number of miniature trees, shrubs and plants within a short space of time, and some outside professional help with stone removing in the early stages. The bill reflects the urges not just of an amateur gardener, but an impatient one.

21 Maki…………………………¥190,000

21 Maki…………………………¥190,000

Trees/plants………………….¥160,000

Turf/stone removal………..¥80,000

Black pebbles……………….¥30,000

Millstones………………………¥20,000

Roof tiles………………………¥10,000

Total……………………………..¥490,000

Story and photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, June 2006

-360x230.jpg)

Recent Comments