Though today’s city is a pleasant, relaxed enough place, Aizu-Wakamatsu’s strongest ties are to its past, a history that it draws nourishment from in the present and uses to fill out the otherwise rather featureless contours of the city. A major castle town on the all important trunk road north from Edo, the city’s fortunes took a turn for the worst with the collapse of the Tokugawa shogunate, a historical development that threatened to relegate it to the backwaters. The region’s powerful Matsudaira clan was among a fierce minority who had resisted the movement to reinstate the emperor to a central, albeit symbolic role in Japan, a decision they paid a high price for. Doomed from the outset, the 1868 Boshin War, a short-lived conflict coming just a few years after America’s bloodier version of internecine strife, raised the long buried specter of national division.

Though today’s city is a pleasant, relaxed enough place, Aizu-Wakamatsu’s strongest ties are to its past, a history that it draws nourishment from in the present and uses to fill out the otherwise rather featureless contours of the city. A major castle town on the all important trunk road north from Edo, the city’s fortunes took a turn for the worst with the collapse of the Tokugawa shogunate, a historical development that threatened to relegate it to the backwaters. The region’s powerful Matsudaira clan was among a fierce minority who had resisted the movement to reinstate the emperor to a central, albeit symbolic role in Japan, a decision they paid a high price for. Doomed from the outset, the 1868 Boshin War, a short-lived conflict coming just a few years after America’s bloodier version of internecine strife, raised the long buried specter of national division.

The single most tragic event in Aizu-Wakamatsu’s own chapter of the conflict was the mass suicide of the Byakkotai (White Tigers), a band of twenty teenage samurai who mistakenly believed the castle had fallen to pro-Restoration forces. One of the teenager’s was saved before he bled to death. Forced to spend the rest of his life with an abdominal scar, a mark of having failed to die according to the prevailing code of honor, the surviving member of the band had no reason to thank his rescuers. As it happened, the siege by imperial forces would take several weeks before the city fell, defeated in the end not by fire, but food shortages. Twice a year, April 24 and September 24, local school children, brought up to revere the young victims as heroic role models, re-enact the suicides.

Iimoriyama, the hill where the group, the oldest of which was a mere seventeen committed ritual disembowelment, has become a must-see tourist sight. It is also a sacred spot for nationalists. A classic example of the Japanese admiration for noble failure, the Westerner may have mixed feelings about the beauty of wasted youth, the enthrallment in the glory of the futile or misconceived. Perhaps it is a question of ideology rather than any imagined East-West perceptual divide. Certainly the rising Fascist party in Italy felt a strong empathy with the act. In 1928, in honor of the fallen youths, they sent a marble column topped with a bronze eagle to the site. It can still be seen on the hill where they are buried.

A little further down the hill, is a hexagonal Buddhist temple called Sazaedo. Constructed in 1796, the design, consisting of two ramps spiraling around a central pillar in the manner of some temple structures in Thailand, is arresting. The main hall contains 33 Kannon statues representing 33 pilgrimage temples. The building is cleverly constructed so that you never need to revisit the same spot twice. The summit of the hill can be reached on foot or, in the wonder-world of modern conveniences brought to Japanese historical sights, by escalator.

Tsurugu Castle–also known as the Crane Castle–has stood at the heart of the city since the 13th century, but the present construction, a five-storey 1965 replica, was rebuilt as a museum, reducing some of its martial authority. Once inside the castle, the rather too wide staircases and linoleum flooring are another giveaway, hinting at a more recent approach to interior design. The landscape gardens have also been restored, but how closely they are modeled on the original layout is unclear. The parkland around the castle is still a great place to stretch and stroll, and in the spring roughly one thousand cherry blossoms turn the area into a foaming mass of pink. The massive stone ramparts, as you often find with castle sites, are the originals; as such, their grandeur rather overshadows the diminutive fortress within. Most of the city’s buildings were burnt down in the siege of the castle. One surviving item is a 400-year old teahouse, returned to the castle grounds in 1990 by the family who removed it from the flames.

Tsurugu Castle–also known as the Crane Castle–has stood at the heart of the city since the 13th century, but the present construction, a five-storey 1965 replica, was rebuilt as a museum, reducing some of its martial authority. Once inside the castle, the rather too wide staircases and linoleum flooring are another giveaway, hinting at a more recent approach to interior design. The landscape gardens have also been restored, but how closely they are modeled on the original layout is unclear. The parkland around the castle is still a great place to stretch and stroll, and in the spring roughly one thousand cherry blossoms turn the area into a foaming mass of pink. The massive stone ramparts, as you often find with castle sites, are the originals; as such, their grandeur rather overshadows the diminutive fortress within. Most of the city’s buildings were burnt down in the siege of the castle. One surviving item is a 400-year old teahouse, returned to the castle grounds in 1990 by the family who removed it from the flames.

Fukushima Museum is just outside the east gate of the castle and well worth a look for its models and dioramas of local history, spanning two thousand or more years. The Aizu Sake History Museum is even more interesting, housed in an original wooden building where the Yamaguchi family has been brewing sake for over 350 years. It provides a superb introduction to the sake making process. Abundant supplies of good water and a mountain climate have made the region known for the high quality of its sake. The real center of production is not within the city boundaries though, but at Kitakata, north of Aizu-Wakamatsu. If your interest has been aroused by the museum, it’s well worth the trip, as there are a number of sake breweries and old storehouses open for inspection.

A more successful reproduction of the past than the castle, is the Aizu buke-yashiki. A samurai residence owned by one Saigo Tanomo, a high-ranking retainer of the Aizu clan, the replica is faithful right down to its reconstruction of 38 separate rooms, reception areas, a cypress bathtub and sandbox toilet. In addition to the main manor house, some authentically old buildings, including a thatched shrine and rice mill, have been added to the grounds. The complex conveys a good idea of the comfortable lives enjoyed by a privileged strata of upper ranking samurai, indoctrinated at the same time to be prepared for death at any moment. They didn’t have to wait long. On his return from combat in the Boshin War, Tanomo found that, under siege, his entire family had committed suicide rather than be taken prisoner.

A more successful reproduction of the past than the castle, is the Aizu buke-yashiki. A samurai residence owned by one Saigo Tanomo, a high-ranking retainer of the Aizu clan, the replica is faithful right down to its reconstruction of 38 separate rooms, reception areas, a cypress bathtub and sandbox toilet. In addition to the main manor house, some authentically old buildings, including a thatched shrine and rice mill, have been added to the grounds. The complex conveys a good idea of the comfortable lives enjoyed by a privileged strata of upper ranking samurai, indoctrinated at the same time to be prepared for death at any moment. They didn’t have to wait long. On his return from combat in the Boshin War, Tanomo found that, under siege, his entire family had committed suicide rather than be taken prisoner.

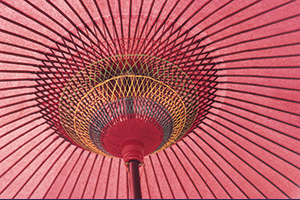

A relatively unsung highlight of the city, if the trickle of visitors is anything to go by, is the Oyaku-en, a 17th century villa and garden. Laid out by the lords of Aizu as a retreat, the grounds represent an interesting digest of elements, tastes and personal interests. The walk-around design suggests the themes of a kaiyushiki-teien, or Edo period stroll garden, and there is even a classic kokoro, or heart-shaped pond, to confirm the impression. Leafy arbors, the use of dark green plantings and dewy stepping-stones on the other hand, hint at the aesthetics of the tea garden, and there is in fact, a cottage-style, thatched roof teahouse at the water’s edge. The most remarkable feature for a formal landscape of this period, though, is a large corner of the grounds set aside as a medicinal herb garden. Among the rows of ginseng, gentian, angelica, lycoris and 400 or so other medicinal plants is a rectangular lotus pond, adding interest and breaking up the monotony of expectation. The garden shop sells herbs and flavored teas. It also serves omatcha (powdered green tea), another healthy restorative.

Arguably, the best place to sample green tea served with a delicate Japanese sweet is the traditional teahouse facing the pond. As a rule, I’ve found that chaya like this usually command the best perspectives on Japanese gardens. The rustic elegance of this teahouse, with its framed view that is nothing short of picture perfect, is no exception.

TRAVEL INFO

The JR Tohoku bullet train will take you from Tokyo to Koriyama, where you must change a limited express train on the JR banetsu-sai line for Aizu-Wakamatsu. The sights are spread out over a fairly wide distance. All day bus passes, available at the station bus office, help to get around. Eki Rent-a-Car, in the station building, rents bicycles. The writer Mishima Yukio once stayed at Shibukawa Donya (0242 28-4000), an old and stylish inn that was once a dried fish wholesaler. Try their first rate herring. Green Hotel Aizu (0242 24-5181) is a good value business hotel with a restaurant, just five minutes walk southeast of the station.

The Aizu Aki Matsuri from 22-24 September, has a morning parade that is a historical pageant, with participants dressed as samurai warriors. The city is not known as a gastronomes pit stop, but the Chuo-dori and Nanokomachi-dori have a concentration of moderately good eateries. Worth the effort of finding for its specialty, wappa-meshi, steamed boxed rice with fish, mushrooms and flowering fern, is Takino, in the backstreets southeast of the junction of the above two streets.

Nanuka-machi dori shopping street is lined with old shops selling traditional crafts, including striped Aizu cotton, a paper mache oxen called akabeko, and the highly esteemed Aizu lacquerware. Although it is in the far north of Tohoku, Osamu Dazi’s 1944 travelogue “Tsugaru,” is a masterful account of the region. The tourist information office (0242 32-0688) inside the main station has English speaking staff, good maps and brochures.

Story & photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, July 2009

Recent Comments