Spain has always been regarded as the most exotic and barbarous country in Europe, and foreigners for their part have always tended to romanticize the country. Even the Muslims in the eighth century, casting covetous eyes across the 27-kilometer stretch of water that separates Morocco from Spain, idealized the place as a kind of Africa without the flies, disease or droughts. One wistful Arab poet described it as a region where maidens “as handsome as houris, recline on soft couches in the sumptuous palaces of lords and princes.”

Spain has always been regarded as the most exotic and barbarous country in Europe, and foreigners for their part have always tended to romanticize the country. Even the Muslims in the eighth century, casting covetous eyes across the 27-kilometer stretch of water that separates Morocco from Spain, idealized the place as a kind of Africa without the flies, disease or droughts. One wistful Arab poet described it as a region where maidens “as handsome as houris, recline on soft couches in the sumptuous palaces of lords and princes.”

Spain has always had more than its fair share of style to be sure – “an arrogant and insolent grace,” insisted one French historian – which has set it apart from the rest of Europe. The propensity for excess and grand gestures is regarded as hallmarks of Spanish distinction. “Command your soul to God,” a colonel in the Civil War cried down the telephone line to his son who was being held by the enemy: “Shout Viva Espana and die like a hero!” If the Spanish tend towards the excessively romantic, they are equally an earthy and unaffected lot. “Hombre!” is the customary Spanish greeting – a square-shouldered, no-nonsense courtesy delivered with a vigorous slap on the back or pumping of hands.

The sheer joy of living, the alegria of the Spanish, is nowhere more apparent than in the yeasty south of Spain where the refined and elemental seem to co-exist effortlessly. Andalusian cities such as Jaen, Cordoba and Malaga, though certainly worth a visit in their own right, pale against what many regard as the region’s crown jewel – Granada. On a return visit to Andalusia in the 1950s, poet Laurie Lee described this voluptuous, water-fed town as “probably the most beautiful and haunting of all Spanish cities: an African paradise set under the Sierras like a rose preserved in snow.” It still is. It is also Spain’s most Islamic city, a fact attested to not only in the refinement of the Alhambra palace and gardens, and the labyrinth of streets that make up the old Muslim quarter of Albaicin, but also in its souvenir shops, which pay tireless tribute to North African arts and crafts with their colorful ceramic plates and tiles, bronze water pipes and star-punctured lanterns. Even the city’s impressive cathedral and the palaces of the Catholic kings and queens cannot banish an Arab influence that lasted for almost eight centuries.

Few Spanish cities today can offer as many thrills or as much beauty as Granada does during its celebrated feria, which is held each spring. As hotels discreetly double their prices and whole families are obliged to pay a king’s ransom for the management’s last back room, the pace of the city accelerates too: cafes and bars open until the early hours, splendidly dressed horsemen clatter into town on their Arab steeds, and the streets are requisitioned to satisfy what seems like a long, pent-up urge to dance in public. Despite the crowds, it is a wonderful time to be in the city.

Granada, though, is a generous host at any time of the year. The city of sweet wines, bitter oranges, brooding roadside virgins and doomed bullfighters is still faithfully maintained in spite of the congested roads one finds in most major Spanish cities and the carefully stage-managed marketing of its legendary sensuality and beauty. All the elements that collectively compose the visitor’s preconception of the region are here. These include its bloody and enormously popular corridas (professional bullfights), events that are not for the fainthearted but are an inseparable part, nonetheless, of the Andalusian stage.

Aside from its cultural sights, Granada also offers visitors with the stamina for it a phantasmogoric social round, with bars, restaurants and clubs open late into the night. Some of the best restaurants are scattered among the cavernous alleys around the Plaza Nueva, the cathedral and Albaicin. Here you can bury those dismal memories of eternal gazpacho, leathery pork cutlets and glutinous paella. Here, in restaurants nestling in the shadow of the cathedral, or tucked into a back alley of the old Arab quarter, you can sit down to a bowl of garlic soup, spinach with raisons and pine kernels, partridge in red pepper sauce, goose cooked with turnips or, with a glance in the direction of Valencia and Catalonia, mel y mato, a classic dessert that blends honey and cream cheese. Earthier, more affordable eateries are easily found in the old quarters of Granada as well. On my first night in the city, I sought out one of the city’s taverns and flamenco venues. There I was treated to rustic country bread, grilled sardines and a course black wine, placed unceremoniously on the table along with a rough earthenware pitcher. I ate ravenously of this biblical repast.

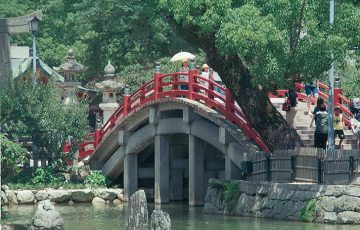

Water has always been the saving grace of Granada, the secret of its lush parks, tree-lined avenues and shady plazas. This gift of water, most evident in spring when the snows of the Sierras melt and gently inundate the city, is the envy of other, more typically arid parts of Andalusia. The well-tended private gardens of suburban Granada and the region surrounding the city that keeps its restaurant tables well supplied – one of lush olive groves, vegetable plots and goat herds – is a far cry from the red earth and cork trees to the north, or the infertile terrain of Algeciras to the east. The serpentine blue lines on maps of Spain that promise cool rivers in which to wet your feet and slake your thirst, frequently turn out to be pebble-strewn tracks fit only for muleteers. The Spanish have clustered around their water holes like herons, raising cities to transform their vision of the acrid, tawny plains that lie beyond. Often, great bridges of stone and marble have been built across these ungrateful trickles; it’s an approach that is typically Spanish – to make a grand gesture in the face of uncooperative water.

Water has always been the saving grace of Granada, the secret of its lush parks, tree-lined avenues and shady plazas. This gift of water, most evident in spring when the snows of the Sierras melt and gently inundate the city, is the envy of other, more typically arid parts of Andalusia. The well-tended private gardens of suburban Granada and the region surrounding the city that keeps its restaurant tables well supplied – one of lush olive groves, vegetable plots and goat herds – is a far cry from the red earth and cork trees to the north, or the infertile terrain of Algeciras to the east. The serpentine blue lines on maps of Spain that promise cool rivers in which to wet your feet and slake your thirst, frequently turn out to be pebble-strewn tracks fit only for muleteers. The Spanish have clustered around their water holes like herons, raising cities to transform their vision of the acrid, tawny plains that lie beyond. Often, great bridges of stone and marble have been built across these ungrateful trickles; it’s an approach that is typically Spanish – to make a grand gesture in the face of uncooperative water.

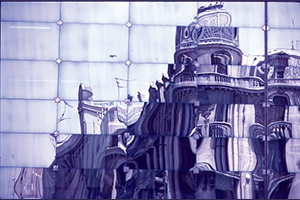

The refined pleasure taken in the proximity of water can still be had in the gardens of the Alhambra palace and Generalife, where shallow pools are said to have been placed in such a way that their surfaces reflect inverted images of the surrounding buildings like a desert mirage. Here, among gurgling fountains, mozaic tiles known as azulejos, royal baths and immensely detailed stone filigree depicting the Arab script in a swarm of complex curlicues, is the ultimate achievement of Arabic art and architecture in Spain. Perhaps the best time to see this dazzling legacy is first thing on a Sunday morning, 9am sharp, before the crowds rouse themselves from late breakfasts and begin creeping up the hill to the ticket office. Admittance to the Alhambra is also free on Sundays.

One of the finest views of the palace and its reddish outer walls that served as a stern fortress to its inner pavilions can be had by climbing up through the narrow alleys and white-washed houses of the Albaicin to the terrace of the church of San Nicholas, where a few cafes have sprung up to serve those who undertake the climb at sunset. The Albaicin, with its serpentine alleys, cobblestone courtyards and houses with window boxes bursting with geraniums and bougainvillea, is occupied by a colorful mixture of Granadans and local gypsies, both inhabiting the same milieu but, in all other respects, treading very separate paths.

Andalusian poet Federico Garcia Lorca wrote that in Granada, more than anywhere else in the world, he had come to understand the experience of the outcast, the gypsy and the Muslim. Lorca, assassinated by agents of Franco’s Nationalist forces in 1936, believed that a good poem should have three things: “Luz, alma y vida” (light, soul and life). The memory of Granada’s best-known literary figure continues to cling to the city. The reasons for his death are still not clear, but stemmed in part no doubt from the popularity among the landless poor of verses he wrote to traditional tunes, and the authorities perception of him as a ヤred’ poet and subversive.

Andalusian poet Federico Garcia Lorca wrote that in Granada, more than anywhere else in the world, he had come to understand the experience of the outcast, the gypsy and the Muslim. Lorca, assassinated by agents of Franco’s Nationalist forces in 1936, believed that a good poem should have three things: “Luz, alma y vida” (light, soul and life). The memory of Granada’s best-known literary figure continues to cling to the city. The reasons for his death are still not clear, but stemmed in part no doubt from the popularity among the landless poor of verses he wrote to traditional tunes, and the authorities perception of him as a ヤred’ poet and subversive.

Born into a family of well-to-do small landowners in Fuente Vaqueros, a village near Granada, in 1898 – the year that Spain lost her last colonies to the United States – Lorca exemplifies more than any other poet Andalusia’s troubled paradoxes: its vivacity and listlessness, arrogance and injured pride, its swings between ecstasy and melancholy, its festivals and death shrouds. Lorca is the south’s great poet of desire, writing of a yearning that often goes unfulfilled.

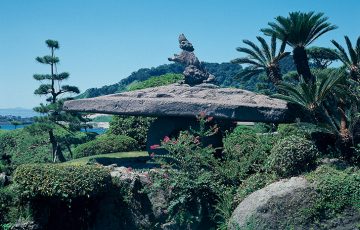

If Granada is haunted and still a little guilt-ridden by the memory of Lorca and the long gone Moors, as the Spanish called the infidels they owe their celebrity to, the city is dominated in the physical sense by the backdrop of mountain ranges known as the Sierra Nevada. The ascent by foot into the Sierras begins from the Alhambra itself, but most people prefer to hire a car for the day, use the buses that serve the area or join a ski tour in the right season. The most interesting part of the Sierras is unquestionably the southern section known as the Alpujarras. Visitors are drawn here to see the region’s Berber villages, built in styles said to be indigenous to the northern mountain eyries of Morocco and Algeria. The beautiful village of Capileira is a good base from which to explore other locations such as Yegen (a hamlet that sits precariously on a summit overlooking a deadly ravine), Pampaneira (the first of three hamlets built above the gorge of Poqueira) and the rural port of Ugijar (where Ulysses made a stop to repair his ships).

From the snow-capped peaks of the Sierra Nevada one may catch, on a clear day, a glimpse of the coast of Morocco. There another range of hills, the Atlas Mountains, blue and permanganate under African skies, shimmer not so very far off in the distance.

Travel Information

Most overseas travelers reach Granada via Madrid and its super express train, or from the resort town of Malaga. The Moorish-style Hotel Saray (travel.yahoo.com/p-hotel-993872_

hotel_saray) has 213 air-conditioned rooms and first-rate general facilities at affordable prices. The very regal AC Palacio de Santa Paula (www.achotelsantapaulagrenada.com), an old restored Andalucian house in the historic district, has 75 air-conditioned rooms with modern facilities. La Gran Taberna del Carmen (tel: 0958-22-6896) along Escudo del Carmen, has great Spanish fare. The combination of broad beans with mountain ham, bull’s tail stew, a side plate of black olives and goat’s cheese from Magaha is difficult to beat. Gerald Brenan’s classic South From Granada remains one of the best reads on the region. A more recent book, Jason Webster’s Duende: A Journey in Search of Flamenco, has an interesting.

Story & photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, June 2007

-360x230.jpeg)

Recent Comments