Kyoto no doubt once had strong rural features, and even today its hills and streams, though meticulously incorporated into the cultural landscape as civilizing features, can be sensed. For a more intimate vision of how nature, agriculture and high culture once co-existed, a visit to Ohara, just forty-five minutes from Kyoto Station by bus, is instructive.

Kyoto no doubt once had strong rural features, and even today its hills and streams, though meticulously incorporated into the cultural landscape as civilizing features, can be sensed. For a more intimate vision of how nature, agriculture and high culture once co-existed, a visit to Ohara, just forty-five minutes from Kyoto Station by bus, is instructive.

The narrow roads that led centuries ago out of Kyoto, crossing steep and perilous mountains and gorges, are long gone, but one route even older than the city itself, survives. The ingloriously named Route 367, wending its way through the northeastern suburbs of the city and ending at the Japan Sea, passes under the shadow of sacred Mount Hie before emerging onto a fertile valley plain and the village of Ohara.

Filaments of morning mist, suspended like ghostly spirits above the rice-fields, vanish as the first rays of light eviscerate the last traces of dawn. A weak sun touches the cross-beams of thatch and corrugated roofs as Ohara’s early risers, many of them elderly women in smocks and bonnets, walk into their fields. If by chance you hear a liturgical chant at this hour, a deep resonance from temples standing in the center of cryptomeria woods, you may feel that this is a truly ancient, detached world, but the mystic character of the area is tempered by the fact that this is also a hard-working farming community. A pleasant bus ride from Kyoto, this village of 620 households, many going back several generations, exemplifies the region’s ties between land and tradition, tight bonds that have ensured its survival and prosperity.

The area has a strong association with ancient Kyoto aristocracy: emperors, empresses, imperial kin and consorts who repaired here for respite and refuge. Retired aristocracy, peasants, high priests and monks co-existed in a simple but rarified atmosphere. Ohara has long been a sacred place for the Buddhist faith, the area compared by poets to the Buddha’s Heaven on Earth. Its otherworldly aspect is captured in its association with shomyo, a form of Buddhist chanting brought from China in the 9th-century.

Officially an outer suburb of Kyoto, Ohara looks and feels far removed from that great city. Not so many years ago it was still possible to see Ohara-me (Ohara maidens) in the streets of Kyoto, young women in rustic garments carrying firewood on their heads. The image remains, but these days it is more likely to be applied to the women dressed in peasant costumes, whose sales pitch invites you to buy local farm products rather than firewood. Many of the residents of Ohara once earned their living making and selling charcoal made from local timber. Smoke from the charcoal kilns once filled the valley.

Officially an outer suburb of Kyoto, Ohara looks and feels far removed from that great city. Not so many years ago it was still possible to see Ohara-me (Ohara maidens) in the streets of Kyoto, young women in rustic garments carrying firewood on their heads. The image remains, but these days it is more likely to be applied to the women dressed in peasant costumes, whose sales pitch invites you to buy local farm products rather than firewood. Many of the residents of Ohara once earned their living making and selling charcoal made from local timber. Smoke from the charcoal kilns once filled the valley.

The legacy of beauty, calm and tradition clearly appeals to the handful of textile artists, potters and writers who have settled in Ohara. There is even a foreigner here who has made the village her home: Venetia Kajiyama, a 10-year British resident of the village, a garden guru who has made her own secular paradise in green and pleasant surroundings that combine the flowers, plantings and horticultural tastes of her native country with the sensibilities of the Japanese rural garden.

An insight into the way that ordinary people lived in this naturally well-endowed area can be glimpsed in the Ohara Kyodokan, a 19th-century farmhouse that has been turned into a folk museum. The rushing stream here turns a wooden waterwheel standing beside a thatch-roofed gate. The wooden household utensils, farming tools, and furniture convey the sense of a basic, but not uncomfortable existence.

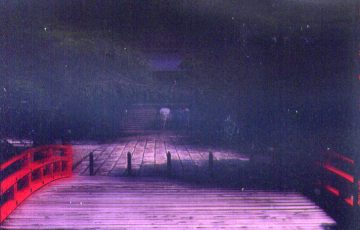

Ohara divides itself into two sections, east and west of the only moderately busy Route 367. A model of harmony and balance with nature, ancient stone-sided paths and wooden footbridges wind through fields, passing brooks and Meiji period farmhouses.

Ohara attracts a steady trickle of visitors, though most remain within the main temple district. Fall is perhaps, the most popular time to visit, a season when the “mountain maple magic” as the local expression goes, of red, orange and flame colored leaves blanket the hill sides, contrasting with the yellow of ripening, pre-harvest paddies. Summer’s lush green carpet is replaced in winter with a silent bed of snow. In clement weather you may be able to sit on the riverside terrace of a restaurant, enjoying a platter of tastefully presented seasonal vegetables.

A lane leading east from the main road winds up a hill beside a stream towards Sanzen-in, Ohara’s most important temple. Tubs of pickles, mountain vegetables, rice dumplings, and a local speciality called shiso-cha (“Beefsteak-leaf tea”), are sold along the way. The tea, which is slightly salty, contains supposedly bucolic flecks of gold.

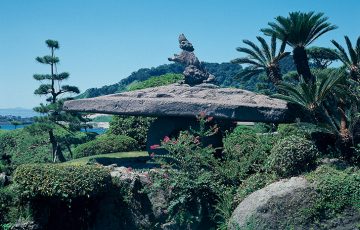

Sanzen-en, like all the sacred sites here, is a sub-temple of Kyoto’s grand Enryaku-ji. Soft, flower-filled gardens, maples and massed hydrangea bushes, replace the towering cedar forests that characterize the surroundings of the parent temple, blending in perfectly with the natural curvature of hill, forest line and mountain. Sanzen-in, standing in moss-covered grounds shaded by towering cryptomeria, is one of the great iconic images of cultural Japan, one extensively photographed and reproduced.

Sanzen-in is an amalgam of buildings, some ancient, others more recently restored. Genshin, the retired abbot of Enryaku-ji temple in Kyoto, had the first Amida Hall built here in 985. An advocate of the Tendai sect of Buddhism, he believed that even the unschooled masses could gain admittance to Amida’s Pure Land paradise through sincere prayer. The hall looks out over the garden, designed to evoke the unearthly beauty of the Pure Land. A statue of Amida, carved by Genshin himself with an intricate arabesque halo, is enshrined here. Incense curls upward to bosatsu and other heavenly bodies, barely visible on the centuries-blackened ceiling, adding to the aura of divinity and the sense of occupying a delicious space between heaven and earth.

More earthly delights are laid out in the gardens above the temple where rhododendrons and bush clover make way for a newer hydrangea garden created by a former abbot of Sanzen-in. The earth is acidic on the hillside here, so the flowers are a watercolor-blue. The hydrangea, all three thousand bushes of them, are best seen during the June rainy season. A gravel path above Sanzen-in leads to Raigo-in, a temple located in a little visited clearing in the forest. The main hall is still used for the study of shomyo chanting. To hear these incantations issuing through this world of trees and timber buildings is highly evocative.

According to local legend, you are not supposed to hear Otonashi-no-Take (“Soundless Falls”), but if you continue up the same road a gentle splashing sound will soon be detected. The cascade is located amidst maple trees, cedar and clumps of wisteria. You cross a wooden bridge over a second river, the shallow, fast-flowing Ritsugawa, to reach the front lawn of Shorin-in, a temple often overlooked by visitors. An appealingly under-maintained garden, its main hall, a nicely weathered wooden building, dates from the 1770s.

Nearby Hosen-in is distinguished by a magnificent, 700-year-old pine at its entrance. The unusual form looks vaguely familiar, turning out to be clipped into the resemblance of Mount Fuji. The inner crane and turtle garden is framed like a painting or horizontal scroll by the pillars of the tatami room visitors sit within to contemplate the scene while sipping green tea served with a delicate Japanese confection.

Nearby Hosen-in is distinguished by a magnificent, 700-year-old pine at its entrance. The unusual form looks vaguely familiar, turning out to be clipped into the resemblance of Mount Fuji. The inner crane and turtle garden is framed like a painting or horizontal scroll by the pillars of the tatami room visitors sit within to contemplate the scene while sipping green tea served with a delicate Japanese confection.

The lugubrious but atmospheric Jakko-in, built as a funerary temple for the emperor Yumei in 594, lies across the fields along a lane lined with old houses and shops selling yet more varieties of pickles and local products. The temple is associated with the renowned Tales of the Heike, where it is described as a nunnery inhabited by the Empress Kenreimon-in. The compact garden here bears a remarkable resemblance to its description in the book.

If your thirst for solitude needs further quenching, a forty-minute walk north of Jakko-in leads to Amidaji temple in Kochitani (the Valley of Ancient Knowledge). A large Chinese-style gate marks the entrance to the route, a further twenty-minute walk through an eerily still maple forest. There are no restaurants, shops or souvenir outlets here, just the authority of nature. One day these time-worn buildings will be restored or reconstructed in gleaming yellow wood and fresh paint, but for now the faded colors, uneven floors and the musty air of wooden halls and corridors, only adds to the ancient mystique of the valley.

TRAVEL INFO

Look out for the red and cream colored Kyoto Bus company vehicles that run every 30-minutes to Ohara from outside Kyoto station. Stop number 17 and 18. The journey takes around 45-minutes. Seryo, near Sanzen-in, is a good place for lunch, with a local bento featuring fresh vegetables. The restaurant doesn’t open until 11am. The restaurant also runs an excellent ryokan (Tel: 075 744-2301) if you would like to stay overnight. Most of the stalls, shops selling local products and souvenirs, as well as the tea shops are in the main temple area. If you start reasonably early, Ohara makes a comfortable day trip.

Many buildings here have reddish, rust-colored surfaces called benigara, a tone found in typical farmhouses throughout this region, adding a charm and rusticity to the contrast between walls and green rice-fields. Many of these thatch roofs have been covered in gray and orange tin to prevent fires.

Story & photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, October 2009

Recent Comments