Donald Richie, passing through the seaport of Onomichi in the late sixties, described it at length in his magisterial, The Inland Sea. Noting the crescent of old wooden houses along the waterline, several of which are still there, he observed “Onomichi is from the sea a very Chinese-looking city, the houses emptying directly onto the water.” The same view reminded me of some of the more grubby port towns along the Yangtze River, sites that reveal little on first impression, but much once penetrated.

Donald Richie, passing through the seaport of Onomichi in the late sixties, described it at length in his magisterial, The Inland Sea. Noting the crescent of old wooden houses along the waterline, several of which are still there, he observed “Onomichi is from the sea a very Chinese-looking city, the houses emptying directly onto the water.” The same view reminded me of some of the more grubby port towns along the Yangtze River, sites that reveal little on first impression, but much once penetrated.

In reverse view, from the crown of the town out to sea, the hilltop summit of Senko-ji temple in Onomichi, it is possible to view a compression of green and purple peaks, one stacked behind the other as they dissolve into haze. This benign image, green and charcoal-colored stones set in waters of silver halide come to mind, is real enough, but also blighted by petro-chemical plants, squalid port installations, and the stanchions of giant, largely unused bridges.

There are over 750 inhabited islands in this sea, but you don’t have to be on an island to take in a view of the seascapes of this still beautiful region. The Inland Sea’s principal middle port, it was once the haunt of pirates who had the temerity to build a fortress there. It’s always seemed curious to me the way the Japanese equate piracy exclusively with Western countries, particularly the English and Spanish during the Age of Exploration. There’s a rich historiography for someone willing to put in the legwork and research the topic. Japanese pirates were highly active at one time in the waters of South-East Asia, even venturing up the Mekong River into the port settlements of Cambodia, where they sacked and looted in the manner of sea rogues the world over. In the case of Onomichi, the narrow stretch of water between the town and Mukaijima, the island just across the strait, was easily defended, booty could be brought up the town’s discreet little creek, goods hidden in storehouses and caves. Its complex warren of lanes and paths were augmented with countless escape routes. Today, even with the aid of a decent map, it still takes a good half-day to decipher the inner town.

Interestingly, the opening scene in Ozu Yasujiro’s 1953 film ‘Tokyo Story’, takes place not in the capital of the title, but the seemingly unchanging Inland Sea port of Onomichi. A character in the film notes that, spared the aerial bombing of WWII, the town has remained remarkably intact. With the exception of the expanded port facilities and the presence of one or two business hotels and cafes, the same could be said today. Perhaps that is why it has found itself the setting for more recent backdrops, such as the 2005 anime fantasy series ‘Kamichu,’ and Toshihiko Kobayashi’s romantic manga, ‘Pastel.’ Weathered and timeworn to this day, Onomichi remains a town that extends an unaffected welcome to visitors. Ozu would have appreciated this stubborn decency and good manners, qualities that are often called into question in the director’s films about Japanese family life.

Onomichi is not a large town, certainly not a city, though that may be its official designation. A long, narrow place, it is built in the only space available, between a contoured cliff and the sea. Its name, aptly enough, means “Tail Road.” Hugging the railway track, there is only one main road through the town, which is divisible into two sections: an older, more permanent teramachi (temple town), with an appropriate pace of life and a strong sense of order and purpose to go with it, and the more polymorphous working town. The railway line transects the two, the older town rising in stone steps and paths from the level crossings of the JR Sanyo line.

Onomichi is not a large town, certainly not a city, though that may be its official designation. A long, narrow place, it is built in the only space available, between a contoured cliff and the sea. Its name, aptly enough, means “Tail Road.” Hugging the railway track, there is only one main road through the town, which is divisible into two sections: an older, more permanent teramachi (temple town), with an appropriate pace of life and a strong sense of order and purpose to go with it, and the more polymorphous working town. The railway line transects the two, the older town rising in stone steps and paths from the level crossings of the JR Sanyo line.

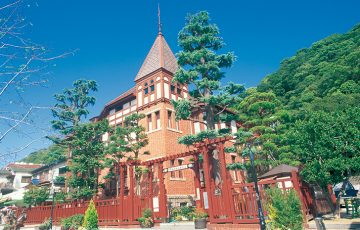

‘Murray’s Handbook for Japan’, first published in 1884, describes Onomichi as “a town of fine, though decaying temples.” One of the charms of the town is that its historical buildings are adequately maintained, but not pampered into showcase sterility. A good place to start an exploration on foot is Senko-ji temple. If the walk up to the peak of Senko-ji Park seems too daunting, a ropeway will get you up the wooded slopes where cherry blossoms and azalea bloom in spring. The scarlet-colored temple sits precariously on the rock face here, bulging with votive tablets, devotional offerings and moldering Jizo statues. Downhill from here leads you along the so-called “literary path,” a series of winding lanes and alleys inscribed with stone plaques to famous figures in Japanese fiction.

Some, including Fumiko Hayashi–her statue stands outside the shopping mall–and Naoya Shiga, actually lived in Onomichi. Down the hill is an extraordinarily well-preserved three-tiered pagoda with another sweeping view of the town. East of here are more temples. Onomichi has almost thirty, including Fukuzen-ji. The alley leading to the temple, called Tile-ko-michi, is covered in colorful pieces of ceramic, which visitors have bought and written messages on. The spacious grounds of Saikoku-ji are an inspiration to travelers. Pray at the base of a pair of giant sandals hanging at the entrance to the temple and your journey, it is said, will be fruitful.

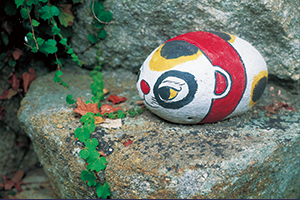

If this older and larger section of town is properly weathered and timeworn, there are antique smells to accompany it as well: incense, drains, mildew, mosquito coils, the older, green variety, sawed timber, cat’s fur. And cat’s piss. Onomichi is a city of cats. There was even a TV program on the subject. Does this obsession with cats come, perhaps, from the idea they are fleet-footed deities that promote fishermen’s efforts, swelling their nets? For cat lovers–and there seem an inordinate number of them in Onomichi–the litter of unsightly trays, the fish heads, messily pawed canapés, and cans of reeking cod and tuna oil, do not appear unsightly, just part of the paraphernalia of feline care. There is even a Maneke-neko Museum, perhaps the only town in Japan with such an institution, dedicated to those tacky models of cats with beckoning paws employed by restaurant owners and the like. The museum offers the usual knickknacks and cat theme trinkets for those interested in such things. East of the museum, at the Jodo-ji Temple along the ridge of the old quarter, the Misho teien is a superb dry landscape creation dating from 1806. A guided tour through the gloomy interior of the temple, it seems, is obligatory before you are allowed to view this sublime and little visited garden.

If this older and larger section of town is properly weathered and timeworn, there are antique smells to accompany it as well: incense, drains, mildew, mosquito coils, the older, green variety, sawed timber, cat’s fur. And cat’s piss. Onomichi is a city of cats. There was even a TV program on the subject. Does this obsession with cats come, perhaps, from the idea they are fleet-footed deities that promote fishermen’s efforts, swelling their nets? For cat lovers–and there seem an inordinate number of them in Onomichi–the litter of unsightly trays, the fish heads, messily pawed canapés, and cans of reeking cod and tuna oil, do not appear unsightly, just part of the paraphernalia of feline care. There is even a Maneke-neko Museum, perhaps the only town in Japan with such an institution, dedicated to those tacky models of cats with beckoning paws employed by restaurant owners and the like. The museum offers the usual knickknacks and cat theme trinkets for those interested in such things. East of the museum, at the Jodo-ji Temple along the ridge of the old quarter, the Misho teien is a superb dry landscape creation dating from 1806. A guided tour through the gloomy interior of the temple, it seems, is obligatory before you are allowed to view this sublime and little visited garden.

A surprisingly large (disproportionate would be a better word) red light area exists in the newer, but unremittingly rundown postwar section of town, there presumably to serve the male population of the area. It is located between the waterfront and the railway tracks. Fittingly for a water trade district, its grubby bars, pink cabarets, and small soapland establishments, are located near the fish restaurants, quays, and ships’ chandlers of the water front area. A number of florists have set up shop as well. Places like this always have flower shops where customers who feel flush, or indebted, can pick up a bouquet for their mama san. The quarter may have seen better days, but at night it is the brightest place in the town. Outside of its sputtering electric periphery is a world plunged into half-darkness, as if the town were blighted with the first stages of a power outage.

Night, however, covers up things best not seen: the grimy industrial complexes, unlovely shipyards, and cement protrusions. At twilight the water channels glow, not with diesel emissions, but with the phosphorescence of lights reflected from ferryboats, fishing skiffs, and off illuminated bridges that cross to islands hinting at further journeys across the sea.

TRAVEL INFO

The bullet train stops at Shin-Onomichi from which it is a 15 min. ride by bus to town. The JR Sanyo line is direct. There are also buses from Ikuchi-jima island and Hiroshima airport, and ferries to Setoda and other islands. Onomichi is a convenient entrée for many other islands, on foot, by cycle across the network of bridges that start here, or by ferry. The spacious and graceful Uonobu Travel (Tel: 0848-37-4175) is expensive as well as expansive, with excellent meals included. Cheaper options are the business hotels: the Dai-Ichi Hotel (0848-23-4567) near the station, and the Alpha 1 (0848-25-5600), both with single rooms in the ¥4,500-6,000 range. As a port with a healthy fishing fleet, seafood is the obvious thing to go for here. The best restaurants are right along the quay with the day’s catch in the plastic buckets and glass tanks. Shimizu, a tiny, three-table joint serves an excellent sea bream dish, and is very cheap. There are several more restaurants and cafes in the arcade. The Tourist Information office is just to the right of the train station. They have good walking maps in English. Donald Richie’s classic, The Inland Sea, is an excellent companion for this area.

Festivals & Events: Ceremony Of The Holy Flame, January 8: A fire walking ceremony to pray for good health, business fortune and peaceful households at Saikokuji Temple. Onomichi Minato Port Festival, 4th Saturday and Sunday in April: Taking place in front of the station, in the shopping arcade and throughout town is a celebration of the start of construction of Onomichi harbor in 1740. Parades and other events. Water Festival, end of July: A puppet/magic show at the Kumano-Gongen Shrine, featuring puppets which squirt water from their hands.

Story & photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, December 2009

Recent Comments