Rob Gilhooly explores a 14-billion-ton block of salt in the middle of South America.

Had it been part of some bizarre dream, it might have been more credible. After hours of driving along unsealed tracks that snaked through windswept villages straight out of a Sergio Leone movie, we entered what looked like a vast, open-air skating rink.

On its glassy surface stood row upon row of meter-high pyramids made of what resembled millions of minute diamonds glistening in the midday sun. Perched on one – like bandits guarding their loot – were two men sharing a flask of something warm.

A hundred meters or so beyond them a red truck sped soundlessly across the endless white expanse. For an instant, it seemed to take flight, like some wingless, bloodied bird soaring through woolly clouds and a sky made fantastically blue by the thin air and blinding white below. The men looked on through plumes of steaming tea, one whistling the unmistakable melody of “El Condor Pasa.”

Yet, this was no dream, nor was it the imagination running wild on the rarefied air. We were standing on the Salar de Uyuni, the globe’s largest salt lake. The crystal cones were in fact piles of freshly mined sodium chloride and the flight of the Isuzu a trick of the eye contrived by near-perfect reflections in a shallow, glassy covering of water on its surface.

A bizarre sight, indeed, but not entirely out of keeping with this southwestern corner of Bolivia.

Long a victim of drug wars and political unrest, Bolivia is less readily associated with tourism than its more frequently visited neighbors Brazil, Peru, Chile and Argentina. More popular images of the country will likely include the near-mythical, such as Che Guevera, or Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid – none of them Bolivian, though all were killed here while performing their very different takes on liberation.

Yet, Bolivia, whose lofty locale and strong indigenous culture has earned it the nickname “Tibet of the Americas,” lays claim to some of the continent’s most precious natural treasures. The Amazon, Lake Titicaca and the Pantanal all lie within a nation almost three times larger than Japan, but whose population is less than that of Osaka prefecture.

Then, there is the Uyuni salt lake, 12,000 square kilometers of almost uninterrupted white nothingness and the centerpiece of a region replete with landscapes as surreal as a Salvador Dali painting.

For the intrepid traveler, much of Uyuni’s charm lies in its isolation and relative obscurity. There are no flag-toting tour groups here and creature comforts are few. In fact, it is possible to travel an entire day through this region without encountering another traveler, save for those sharing your four-wheel-drive and its driver.

And not without reason: just getting to Bolivia is a challenge. Flights from Tokyo take the best part of two days, and having finally landed in the capital of La Paz you are guaranteed a headache from the time you alight: at 4,100 meters, El Alto airport is the most elevated airport in the world.

From here it’s a lengthy journey by train or bus to Uyuni, which is located on the country’s Altiplano – or “high plains” – and boasts temperatures that would test even the most seasoned sherpas. Buses, whose only knowledge of the word “suspension” would seem to be during the country’s frequent strikes, take between 14 and 20 hours while trains can be a little quicker, though departure times are as rigid as a Romanian gymnast.

Those who do make the effort are rarely disappointed: this region is guaranteed to take your breath away – metaphorically and literally.

It all starts at our hotel. Located several kilometers out of Uyuni town but within sight of the lake, the otherwise functional building is constructed almost entirely out of blocks of salt – right down to the beds. Rather like the Lapland ice hotel that serves drinks “on-the-rocks,” you’d be forgiven for thinking refreshments would enthusiastically embrace the local specialty. Unfortunately, however, there’s not a Salty Dog or Margarita in sight, and the barbequed llama and vegetable soup dinner is a touch on the bland side. Less surprising was the proprietor’s rather strained laughter at “pass the pepper” jibes.

While independent travel is not unheard of, the only way for visitors on a schedule to experience this region is to hire a guide and four-wheel-drive, and there are several companies in Uyuni town offering tours of varying duration. Service quality is generally reflected in the tour company’s rolling stock, and it is not unheard of to come across land cruisers with wheels secured by rope.

Thankfully, none are as ancient or clapped out as the vehicles found at the “Cementario des Trenes,” the first stop on our four-day expedition. The only sleepers in this unique graveyard are those beneath two long lines of late 19th-century steam locomotives and carriages, whose decaying carcasses have been laid to rest in a broad expanse of windswept dessert, as if in wait of another Butch and Sundance era.

It is from this terrestrial time warp that we enter the blanched, otherworldly environs of the salt lake. Even a pinch of raw sodium chloride on the tongue is insufficient to wake you from the feeling that it’s all a trick, that a gust of wind will blow open a backdrop to unveil the greens and browns of the “real” world, or that a whitewashed manhole lid will flip open and Jim Carey will emerge in a white suit and even whiter, toothy grin to tell you it’s all just a show.

But Hollywood this is not. The lake is a legacy of an inland sea that 45,000 years ago covered much of southern Bolivia. Over a period of 15,000 years or so this sea evaporated leaving behind a 14-billion-ton block of salt, which in some places is said to be 10 meters deep. Some 20,000 tons is excavated annually, most of it for household consumption.

Depending on the season, its surface is either covered in a shallow layer of water, turning the lake into a giant mirror, or it is marked by a maze of hexagonal patterns where the water has evaporated and salt crystals have formed. Whatever the time of year, the reflective powers of the lake are astonishing, making decent sunglasses and high-factor sunscreen indispensable travel items.

While little is known about the pre-Inca civilizations that once inhabited this region, the name of a small island that punctuates the otherwise unbroken expanse of whiteness like an ink blot on bleached paper provides a hint as to what may have been a food-source. Rising about 30 meters above the lake, Isla de los Pescatores, or Fisherman’s Island, is little more than a rocky mound, but in this region the eye is easily deceived.

Dodging giant cacti, thousands of which stud the island, I slowly clambered toward the summit, head throbbing and panting like a parched Saint Bernard. Half way up, I stopped to take in the view, expecting to see my fellow travelers – who I had left what seemed like hours before – as mere specks on the lake below. Instead they were a dropkick away, engaged in a game of slow motion soccer, some collapsing in a heap on the lake’s crusty surface after each labored kick.

Situated at a heady 3,700 meters above sea level, the rarefied air here means shortness of breath, headaches and nausea are almost guaranteed for travelers. Even in its mildest form, altitude sickness is worse than the dreaded “Delhi belly” for travelers as it saps the energy and kills enthusiasm for pretty much anything – including sleep. That evening, crammed into basic dorm accommodation in a small, ghost town-like Quechuan village, dinner was pushed aside in favor of bed, though sleep was fitful due to debilitating headaches.

While many find their appetite dulled, maintaining liquid levels is of greatest concern, and a local villager brought me a cup of mate de coca – tea made from coca leaves that is not only nourishing but a local panacea well known for helping overcome altitude sickness. It’s an acquired taste, but later I graduate to an even more typical Andean custom of chewing the leaves, which speeds up the impact considerably, but numbs the inside of the mouth like a dentist’s anesthetic.

Sadly, the desensitizing effects are equally short-lived. Nausea returns with a vengeance the following day as our route ascends to elevations of just under 5,000 meters, passing through barren landscapes of ochre browns and deep reds, broken occasionally by snow-sprinkled peaks and valleys sporting fantastical rock formations.

At one point we stop to stretch our legs in a broad valley covered with orange pebbles so perfectly groomed that one could imagine it being maintained by a team of eccentric Japanese gardeners armed with giant rakes.

At the oddly named village of Colcha K, we pass through a military checkpoint – a reminder of the strained relations Bolivia holds with nearby neighbors Chile and Paraguay. Though landlocked today, Bolivia once stretched as far as the Pacific Ocean to the southwest and the Grand Chaco to the southeast, but a series of conflicts has reduced the country’s territory by half since it gained independence from Spanish rule in 1825.

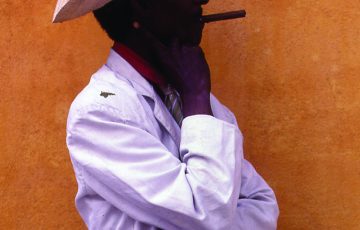

The diminished returns have had one conspicuous outcome: Bolivia has the highest indigenous population of all South American countries, with the majority claiming pure Amerindian lineage. Indigenous languages flourish in a nation where Spanish has been the dominant tongue since the conquistadores arrived more than 500 years ago. Deference to the Andean deities Pachamama and El Tio continues despite 95 percent of the population professing Catholicism, another remnant of the occupation era.

That the native people, who are mostly farmers, have suffered severe discrimination at the hands of the descendents of white settlers is well documented, and the recent election of the country’s first wholly indigenous Indian leader, Evo Morales, himself a former herder and farmer, is a sign of Bolivia’s desire to address the imbalance and to protect its indigenous identity.

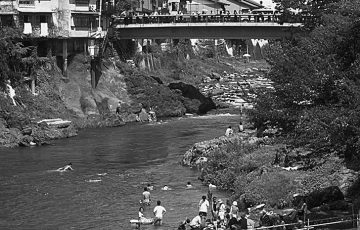

The image of a desperate, marginalized people instigating strikes and bloody protests – often quashed by brutal governmental force – may be a dominant one, but it would be misleading to portray indigenous Bolivians as aggressive or unfriendly, though attacks on solo travelers in the Uyuni region have been reported.

Like Morales, our driver, a quiet man with a lined, weather-beaten face, was of Aymara descent. For two days I didn’t hear him speak a word, until, seeing my ongoing battle with the altitude, he offered me a cup of tea from his battered thermos flask, muttered some words of encouragement and smiled the kind of warm, toothless grin that is as soothing as any panacea.

His incomprehensible words must have been directed to Pachamama, an Inca word originally meaning Mother Earth and signifying harmony with the environment, for my battle with the altitude magically subsided.

From here, we visited a series of high-altitude lakes remarkable not only for their stark settings but also for their striking colors. Minerals leached out from the surrounding mountains react with algae and other organisms to produce chemical cocktails of milky whites, greens and reds. Just to add to the dazzle of color, each is populated by rare breeds of flamingoes, whose varying degrees of pinkness are dictated by the chemical mix of the lake they inhabit.

In between the lakes we passed through more bizarre landscapes, including the bleak Siloli Desert littered with rocks wind-whipped into a variety of outlandish shapes. One distinctly resembled a gnarled tree and it came as little surprise when I later discovered it is known locally as “Arbol de Piedra” – Tree of Stone.

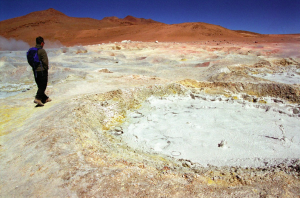

Ascending to a geyser basin at an altitude of some 4,850 meters, we stopped for a wander around an area of bubbling, gas-belching fumaroles and mud pools, unprotected despite reports of severe burns caused by occasional cave-ins.

With time to kill, we were guided to a less hazardous way of enjoying the region’s geothermic and volcanic activity – a thermal pool that our driver assured is little-known even among locals. It was a fantastic setting, perched on the edge of an almost dry but nonetheless picturesque lagoon, whose multicolored floor was backed by a snow-capped mountain range. But as we approached our hopes of a bathe in undisturbed wilderness were dashed by the sight of another group of travelers – our first since leaving the salt hotel. Some were clad in bikinis and surfer shorts, another surreal sight considering the altitude and temperature.

We returned to our vehicle, warmed and relaxed for our return journey to Uyuni, the memories of the previous three days as colorful a cocktail as the otherworldly landscapes that formed them.

Then the engine died, and with it our chances of making the overnight train to La Paz. As bits of engine were laid out on the yellow-pink unsealed road, sandwiched between an endless stretch of orange, vegetation-starved desert, unspoiled by searing concrete or human habitation, not a grumble or sigh could be heard.

Story by Rob Gilhooly

From J SELECT Magazine, April 2006

Recent Comments