“Try to imagine Venice or Florence transported to the tropics and left for 50 years without a single coat of paint, a tightened screw, a roof tile replaced.” Havana Run, Les Standiford

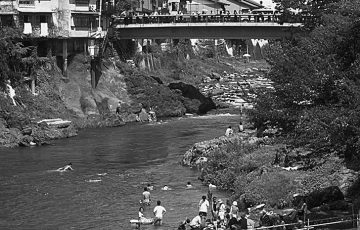

The fishermen along the Malecon didn’t seem to be having much luck. “Turismo,” they said, neither resenting the word nor endorsing it, was ruining the waters. The soda cans and Styrofoam didn’t mix with the crab pots and tackle. The Cuban couples who attached themselves like clams to the seawall every night, adding their own detritus to the foam that hissed underneath them, didn’t seem to care much about the condition of the waters. People bathed in the old coral tanks under the seawall, others dropped votive offerings into the water to the Yoruba sea goddess, Yemaya. Promenade, frontier, Wailing Wall, the Malecon represented whatever one desired.

A six-lane boulevard that only barely fulfills its original function, the Malecon is collapsing in places from salt erosion to the iron rebars inside its mortar. Waves crash over the pitted sidewalk, seawater spurts up from drain-grills, depositing clumps of seaweed on the road. The 19th-century esplanade of peeling mini-palazzos, decorated with plaster garlands and caryatids, stained-glass windows in the Havana style shaped by Moorish tastes, rusting ironwork balconies and massive carved doors studded with nails, is only just being considered for restoration.

The strip plays host to an interesting mix of people at all hours: Cubans dressed in natty suits and white hats, black women smoking cigars, mulattas in Lycra shorts and not much else, an old man selling turnips from a briefcase. Women in curlers lean between the Doric columns of crumbling apartment balconies overlooking the sluggish lanes of traffic, or gossip on broken stairwells. After dark, people linger in doorways, low-wattage light bulbs glow through the shutters of hot, overcrowded rooms, figures move through the darkened scaffolding of what in the United States would constitute million dollar sea-facing plots.

The strip plays host to an interesting mix of people at all hours: Cubans dressed in natty suits and white hats, black women smoking cigars, mulattas in Lycra shorts and not much else, an old man selling turnips from a briefcase. Women in curlers lean between the Doric columns of crumbling apartment balconies overlooking the sluggish lanes of traffic, or gossip on broken stairwells. After dark, people linger in doorways, low-wattage light bulbs glow through the shutters of hot, overcrowded rooms, figures move through the darkened scaffolding of what in the United States would constitute million dollar sea-facing plots.

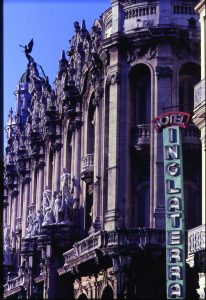

Havana’s architecture elicits surprise, awe and sadness. It’s a mix you find everywhere and in all things. “In Cuba,” Maria Finn Dominguez has written, “nothing is average; it is either heartbreaking or exhilarating.” Here the poor live in the very center of the city, behind decaying rococo and art deco facades, watching their Spanish and neoclassical buildings, high-ceilinged rooms and trompe l’oeil interiors, dissolve in the solution of neglect. Steel reinforcements poke through plaster columns, cornices sag, weeds take root in the cracks of cement porches, window frames peel and curtains become mildewed in the tropical heat. The vast number of 18th-century buildings in Old Havana are made of a porous mix of limestone and small marine fossils that are exposed when the stone matrix is peeled back from years of wind and salt.

Walking through the streets of Havana is like wandering through a library of decaying books, as if touching their parchment-dry walls or pulling on their green, oxidized doorknobs would be enough to bring them down. A Cuban saying has it that “when it rains, it is good for the crops. But today buildings will fall in Havana.” And they do, spectacularly, leaving piles of rubble, exposed steel and dangerously poised half-walls. Under a UNESCO restoration program mostly confined to Habana Vieja (Old Havana), many old mansions have been turned into art galleries, museums and bookstores, giving them a fresh lease of life and opening them to visitors. Habana Vieja, its medina of blackened walls, crumbling balconies and old rum bars paneled with Florentine tiles has its charms, but the real Havana, not forbidden to tourists but largely avoided by them, lies a few streets west.

The paladar in Centro Habana that I visited and returned to on several occasions was on the second floor of a tenement that was a cross between the Bronx and a moldering doge’s palace. A paladar is a privately run restaurant that competes with the more common state run eateries. This place had once been the house of a wealthy family. Painted the color of guava, its plaster had been refaced a half century before, its colonnades decorated with scrolled plaster, lotuses and scarabs, standing out like strange encryptions from distant, long forgotten cultures. The food served there was exquisite.

The fabric of Centro Habana is the most vulnerable in the city. After every cyclone, a few more buildings come down. Resembling the ramshackle streets of an imaginary Spanish-African colony, Centro Habana stands for both the best and worst of the city. It is here that its tutelary spirit resides, not in a dusty shrine, but in the warm flesh of its inhabitants. Life here is lived on the street, or in the semi-outdoors of balconies, darkened doorways and azoteas, rooftops that are either jammed with rusting water tanks, antennae and washing lines, or turned into aerial gardens. At pedestrian level there are small tables set up on the sidewalks for games of dominoes or convivial get-togethers around bottles of aguadiente. Here you will find peso-only bars, 1950s shop mannequins and, sometimes, knives drawn in anger. Despite having one of the lowest crime rates of any city in the world, Centro Habana is one area where you should watch your back at night.

If the old quarters in the center are crowded, the amenities wanting and the buildings dangerously friable, the suburbs are not much better, with whole families living in solares, alleys of one-room apartments so named for the way they soak up the heat. In a quiet suburb of Vedado, the Necropolis Cristobal Colon offers more space to the dead than the living. Although some graves have split open revealing unsettling troves of bones, the necropolis is generally rather better maintained than the city. There are some flamboyant touches: a small Egyptian pyramid, the Bacardi family’s monument with cast iron bats adorning its railings; the tomb of the Cuban chess champion, Capablanca, with a marble bishop guarding it. The piles of dead cockerels, handmade dolls, human images and beads are evidence of Santeria followers. The Afro-Caribbean faith is everywhere. Even Castro is said to be a follower, a son of Chango, lord of lightening and just causes. Whether he is still a practitioner is anyone’s guess, but everyone agrees on the name that he received at his initiation rite: “He who survives, king for all his days.”

Many of the embassies in leafy Vedado, the crumbling sugar mansions in Miramar, the villas in Buena Vista once owned by United Fruit executives are now, judging from the lines of laundry fluttering from balconies, multiple dwellings. Hotels like the Sevilla and Capri are reminders of the days when money talked in a big way. The Hotel National, since restored to its former glory, was where legendary hoods like Meyer Lansky and Charles “Lucky” Luciano once mixed their drinks with the likes of Frank Sinatra, and the Mob’s favorite actor, George Raft. While wealthy visitors and their Cuban colleagues dined out on grilled swordfish, roast breast of flamingo and the flesh of the manatee, the rest of the country got by on a leaner fare. Families searching through hotel trashcans for scraps of food was not an uncommon sight in Havana before the revolution.

Many of the embassies in leafy Vedado, the crumbling sugar mansions in Miramar, the villas in Buena Vista once owned by United Fruit executives are now, judging from the lines of laundry fluttering from balconies, multiple dwellings. Hotels like the Sevilla and Capri are reminders of the days when money talked in a big way. The Hotel National, since restored to its former glory, was where legendary hoods like Meyer Lansky and Charles “Lucky” Luciano once mixed their drinks with the likes of Frank Sinatra, and the Mob’s favorite actor, George Raft. While wealthy visitors and their Cuban colleagues dined out on grilled swordfish, roast breast of flamingo and the flesh of the manatee, the rest of the country got by on a leaner fare. Families searching through hotel trashcans for scraps of food was not an uncommon sight in Havana before the revolution.

The casinos may have been closed down, the cocaine runs out of Florida and the Keys halted, but in other respects Havana has begun to resemble the city that existed before 1959. You won’t see hookers waiting in the airport arrivals lobby these days – at least not yet – but they are just about everywhere else. Cubans have fine-tuned seduction into an art form – and a crime. An evening stroll along the Malecon includes more Havana sensations than a gentle sea breeze. Here and along Paseo de Marti, Virtudes and dozens of other streets in Habana Vieja and Centro, women will stop you with conversation openers like “Que buscas?” and “Momentito, amigo.”

It seems almost as if the suggestive hip-swinging walk, intended to turn heads, was invented in Havana. Stridently feminine, Cuban women do not feel insulted when they are stared at on the street or when they are at the receiving end of catcalls or explicit remarks. As long-time Havana resident Claudia Lightfoot has written, “Cuban women expect and enjoy the piropo, the whispered street compliment… The most convinced revolutionary will find time for her hair and nails.”

Cirilo Villaverde’s description of the sexually iconic mulatta in his 1882 novel Cecilia Valdes, could well describe thousands of women today, sashaying through the black and gold shadows of this broken city: “Her narrow waist contrasting with broad, bare shoulders; the amorous expression of her head and the light bronze color, she could pass for the Venus of a hybrid Caucasian-Ethiopian race.”

Graham Green wrote of a character in Our Man in Havana, that he had “embarked on the great Havana subject; the sexual exchange was not only the chief commerce of the city but the whole raison de’etre of a man’s life.” Green appreciated the seedier side of life here, a place where “every vice was permissible.” They still are, but this time around the decadence is state-orchestrated, run under the watchful eyes of the Havana constabulary. Policemen in gray, well turned out uniforms stand on every street junction, pistols holstered, radios in hand. It’s not clear whether they are “protecting” tourists from locals, or the other way round.

Cubans, despite the surveillance, networks of neighborhood informants and the daily deprivations, are perhaps the most joyful people I have ever met. I think about the young people I have seen with tattoos and pierced ears, the popularity of rap and hip-hop, the social freedoms that seemed, at least on the surface, to exist. Somehow it all seems reducible to music and dance. Cuba in a very real sense is its music, a protoplasmic mix that ranges from son, rumba, danzon and boleros, to trovas tinted with Afro-Caribbean rhythms, Spanish, French and Islamic tonalities. An appreciation of music and dance are the test of Cubanismo and the key to knowing about Cuba. Norman Mailer is said to have regaled President Kennedy after the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion with the remark, “Don’t you sense the enormity of your mistake? You invade a country without understanding its music.”

Cubans, despite the surveillance, networks of neighborhood informants and the daily deprivations, are perhaps the most joyful people I have ever met. I think about the young people I have seen with tattoos and pierced ears, the popularity of rap and hip-hop, the social freedoms that seemed, at least on the surface, to exist. Somehow it all seems reducible to music and dance. Cuba in a very real sense is its music, a protoplasmic mix that ranges from son, rumba, danzon and boleros, to trovas tinted with Afro-Caribbean rhythms, Spanish, French and Islamic tonalities. An appreciation of music and dance are the test of Cubanismo and the key to knowing about Cuba. Norman Mailer is said to have regaled President Kennedy after the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion with the remark, “Don’t you sense the enormity of your mistake? You invade a country without understanding its music.”

Martha Gellhorn, revisiting Havana after a 41-year lapse, concluded that whatever else Cuba might be, it wasn’t a police state ruled by fear. “No government,” she wrote in Cuba Revisited, “could decree or enforce the cheerfulness and friendliness I found around me in Cuba.” Gellhorn, a very fine writer and war reporter, was Ernest Hemingway’s third, though not last, wife. It was she who found their home outside Havana, the Finca Vigia, now the Hemingway Museum.

During my stay I’ve already seen something of the socialist-run Hemingway industry in the city, the bars like Dos Hermanos, Sloppy Joe’s and El Floridita, the writer’s old haunts, where the cost of the drinks reflects his rising stock as a fundraiser for a revolution that he seems to have supported. I think about Gellhorn’s comments about the relative freedoms of Cuba as I drive out to the Hemingway spread, passing Havana’s main train station near the Plaza de la Revolucion. A group of people, bored at waiting in line for their tickets, are swiveling their hips to the sounds coming from a radio placed on top of somebody’s suitcase. Communism in the Caribbean is clearly something else.

At the hotel that afternoon the TV programs are as dour as always. The choice is between a documentary on nationalist hero Jose Marti, a period drama about exploited tobacco farmers in the rural valley of Vinales, a cooking program on making the most of shortages and a state visit by Fidel’s last remaining Latin American ally, Hugo Chevez. I opt for the last, a slice of political theater, set in the anachronism of the present. Despite his age, withering beard and the stiffness beneath the signature olive-green fatigues, Castro’s piercing eyes and barrel-chest dominate the screen. Leaning out of the balcony I can see a wall mural over by the peso-bar opposite: a smiling Che Guevara, looking for all the world like Christ in a beret. I wonder what Che would have made of all this. How much longer did Havana have before the franchises arrived and the place turned into another homogenized, pasteurized Caribbean property opportunity.

Back on the Malecon, the lights are going down over the Straits of Florida. Crowds of people move through dark streets full of sounds, the tempo of the city quickening with nightfall. By the time I return to my hotel, the sound of bongos and marimbas are already floating across the rooftops of Old Havana, the rhythms taken up in dozens of bars and cafes around the city. Drum skins, iron bells and claves. Spain, the old Arab-Moorish world and the Afro-Caribbean joined at the hip, swaying into the night, slightly tipsy, for their last dance in Havana.

TRAVEL INFORMATION

Havana is one of the safest cities in the world, but you should still be watchful on the street with bags and wallets. Another superlative: Cuba has one of the best healthcare systems in the world (free to Cubans), but the usual medical kit for travel is advisable. The Rough Guide to Cuba and the Lonely Planet guide to Havana are first rate. Budget travelers often stay at the friendly Hotel Lido (tel: 07-338-814) in the centrally located Colon district, where rooms with cold showers go for $24. The colonial Hotel Florida (tel: 07-624-127, fax: 07-624-117) along Calle Obispo, is good value at $65-95. Two top-range hotels are the old, centrally located Hotel Sevilla (tel: 07-608-560) at $90-150, and the Hotel Havana Libre (tel: 07-334-011) in Vedado at $100-150. There are several decent restaurants in Old Havana, but if you can find a good paladar, they are great. There are countless books on Havana. Enrique Cirules’s The Empire of Havana is an excellent analysis of the pre-revolutionary US-Mafia ruled city; Pico Iyer’s Cuba and the Night and Martin Cruz Smith’s Havana Bay are intimately described novels set in the city; Jory Farr’s Rites of Rhythm is one of the best introductions to Cuban music.

Story & Photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, November 2004

Recent Comments