Tokyo at night, seen from above, is an intoxicatingly beautiful expanse of sparkling light.

Tokyo at night, seen from above, is an intoxicatingly beautiful expanse of sparkling light.

Of course, the blanket of illumination represents much more than just urban sprawl. One could say the lights, in fact, symbolize the lives of the millions of people in the city – luck changing and destiny colliding with each passing second. Some take their final breaths just as babies take their very first ones; some make love while others explode in violent rages.

Somehow it all seems more profound after the sun goes down. To quote a song by U2, “midnight is where the day begins.”

And so it seems fitting that Haruki Murakami would choose the hours between midnight and dawn as the setting for his latest novel to be translated to English, After Dark.

To those familiar with Murakami’s body of work, the ominous title suggests another tantalizing foray into strange and shadowy territory that has become the author’s trademark.

Discovering Murakami

“There’s no such thing as perfect writing,” Murakami conceded, sitting at his kitchen table late one night in the spring of 1978. “Just as there’s no such thing as perfect despair.” The two sentences would form the very first lines of the first book that would propel him into a novelist’s career – Hear the Wind Sing.

“There’s no such thing as perfect writing,” Murakami conceded, sitting at his kitchen table late one night in the spring of 1978. “Just as there’s no such thing as perfect despair.” The two sentences would form the very first lines of the first book that would propel him into a novelist’s career – Hear the Wind Sing.

Indeed there may be no such thing as perfect writing, and as for perfect despair, he’s probably right on that too. But I can say it was in the midst of (slightly indulgent) gloominess that I discovered Murakami’s magic for myself, and his mystical opus The Wind-up Bird Chronicle can chiefly be credited with dragging me out of it.

At the time, I knew very little about the prolific Japanese writer who was already a superstar in his homeland and quickly becoming one abroad. The neon blue cover of the book’s British edition simply stood out from the rest, and the color probably fit my mood. Most importantly, the book was thick and I was after something that would last a while. Sinking into a novel is like hibernation, and I wanted to escape a world that seemed to become less and less inhabitable each day.

It was late September, 2001.

A lot has happened in the years since, some of it good and some bad, some of it worthwhile and some of it absurd. But thinking back to 2001, it felt like the world had turned completely upside down. A sense of helplessness – or, perhaps, uselessness – prevailed, amid all the uncertainty about the future.

Alone in London, a kind of self-preservation drove me to hole up in my one-room apartment stocked with pre-packaged sandwiches and beer. I avoided cooking in the tiny kitchen, home to a colony of silverfish. As rain trickled down the window in rivulets on a daily basis (at least it seemed that way), and the news carried constant grim reports, I jumped without preconception into the mind of this writer named Murakami. Like so many other readers, I’ve been hooked ever since.

For Jay Rubin – retired Harvard professor of Japanese literature, self-professed Murakami fan and one of the author’s three rotating English translators – it all began with a different book.

“Without a doubt, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World,” says Rubin in an e-mail interview, asked which other Murakami novel he wishes he’d had the chance to translate. “It was the first Murakami work I read and it’s still my favorite.”

He expands on the experience in his biography of the author, Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words. “It absolutely blew me away, so much so that I hardly worked on anything besides Murakami for the next decade.

“When I think back to that first readingノ I remember how much I regretted closing the last page and realizing that I couldn’t live in Murakami’s world any more.”

Rubin wanted to remain in that world so much that he ended up becoming a true Murakami scholar. Along with Alfred Birnbaum and Philip Gabriel, Rubin has brought the author’s unique voice to an English-language readership through his translations of Norwegian Wood, after the quake, the upcoming After Dark and the monumental Wind-up Bird Chronicle.

Of course it was just a coincidence that the main character in The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, Toru Okada, spends a considerable amount of time reflecting at the bottom of a well dug deep in the ground. But it perfectly matched my own state of mind at the time.

Based on Rubin’s study of Murakami, the novel could also be considered symbolic for the state of the world as a whole. It “can be seen as emblematic of human relations in general, which call out for the often painful process of ヤwell-digging’ on both sides. The well thus holds out the promise of healing, which is why Toru goes to inordinate lengths to assure himself of an opportunity to spend time inside it.”

Pulp Fiction or Serious Literature?

There is swirling speculation these days that Japan’s next Nobel laureate is likely to be Haruki Murakami, now 58 years old. In 2006, he added the Franz Kafka Prize from the Czech Republic to his trophy case, and two other previous recipients of the award have already gone on to claim the Nobel honor.

There is swirling speculation these days that Japan’s next Nobel laureate is likely to be Haruki Murakami, now 58 years old. In 2006, he added the Franz Kafka Prize from the Czech Republic to his trophy case, and two other previous recipients of the award have already gone on to claim the Nobel honor.

His body of work grows more impressive with each addition. After Dark (to be released in English on May 8) marks the latest in a line of 11 novels, along with countless essays, short stories and the haunting exploration of the sarin gas attack on Tokyo’s subway system, Underground.

Yet in the face of all this, as well as slow-but-growing recognition from Japan’s traditionally stiff establishment, Haruki Murakami still has his share of critics. His work is sometimes dismissed as fluff not worthy of deep academic analysis, frequently due to the perception that because it’s so popular among the general public it must be inherently shallow.

In his book, Jay Rubin quotes the disapproving professor Masao Miyoshi: “Oe is too difficult, [Japanese readers] complain. Their fascination has been with vacuous manufacturers of disposable entertainment, including the ヤnew voices of Japan’, like Haruki Murakami.”

Miyoshi likens Murakami to the late Yukio Mishima – famously one of Murakami’s least favorite authors – believing, according to quotes in Rubin’s book, that the two share a desire to package Japan for a foreign readership.

“Mishima displayed an exotic Japan, its nationalist side, [whereas Murakami portrays] an exotic Japan, its international version,” says Miyoshi. Murakami is “preoccupied with Japan, or, to put it more precisely, with what [he] imagine[s] the foreign buyers like to see in it”.

Yet this would seem to be a misinterpretation of the Japan seen by idealistic westerners who’ve never been here.

Whereas most non-Japanese seem to be enamored with the traditional Japan of the past or the hyperactive anime culture of the present, Murakami’s work shows us a lot about average daily life in this country. Despite the fantastical elements in his stories, the backbones of his narratives are highly realistic – Murakami’s central characters usually hold mundane jobs, cook simple meals, have encounters with cats, listen to music and find themselves confused by complicated human relationships. In short, they are entirely ordinary people dropped into extraordinary circumstances.

Murakami himself has responded to his critics, who often accuse him of being something less than a “real” Japanese writer.

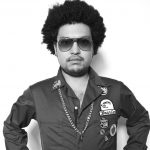

Story by Jim Hand-Cukierman

From J SELECT Magazine, April 2007

-360x230.jpg)

Recent Comments