The Japanese tea ceremony or Sado is an ancient Buddhist-influenced ritual steeped in tradition, which is enjoyed today as a fairly popular hobby by Japanese interested in learning about and preserving their culture.

Drinking tea in Japan traces its roots back to China, from where tea was originally imported and, over the course of several hundred years, grew into the art of Sado. Over time, the Japanese elevated the simple act of drinking tea into a spiritual discipline. After years of practice in Japan coupled with strong Zen influences, “the way of the tea” became synonymous with Zen with “The Spirit of the Tea” and Zen being seen as one and the same. The similarities between Sado and Zen are apparent when one considers that the four precepts of the tea ceremony are peace, respect, purity and tranquility.

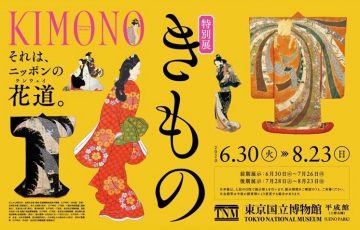

Expert tea practitioners are required not only to know about tea preparation, but also about types of tea, calligraphy, flower arrangement, kimono, incense and ceramics as well their own school’s unique practices and traditions. The need for all of this knowledge makes the study of the tea ceremony a nearly endless pursuit. The ceremony itself is an extremely complicated ritual with almost every movement prescribed and dictated by strict rules governing how the bowl is held, how the tea is mixed and what hand gestures accompany these actions. Even guests attending a formal tea ceremony must be aware of several factors including proper manners and decorum in the tea house as well as the proper gestures and phrases to be used when accepting tea and food from the host.

The equipment for preparing the tea goes way beyond a kettle and cup with numerous specific tools and utensils required. Starting with a chakin a small towel used mainly for wiping the chawan (tea bowl) which come in a variety of sizes; generally a shallow bowl, which allows the tea to cool faster, is used in the summer, opposed to a deeper bowl for winter tea. Then there is the chaire and natsume (tea caddies), which come in many shapes and styles and are made of either ceramic or lacquered or untreated wood. The chashaku (tea scoop) is usually carved from a single piece of bamboo, but can be made from ivory or wood. Finally there is the chasen (tea whisk) that is used for mixing the tea; these are also carved from a single piece of bamboo and when they are old and damaged, they are not simply discarded but are ritually burned at local temples, reflecting the reverence in which they are held.

There are endless varieties to the ways in which tea ceremonies can be performed, but a typical one may begin with the host building a small charcoal fire, which is done in a dictated order. If no meal is served, the host will serve the guests a small sweet or sweets, which are eaten from a special paper that guests carry either in a special wallet or tucked into a fold in their kimono. Following this, each utensil is then ritually cleaned in the presence of the guests and they are then placed in an exact pre-arranged order. When this process is complete, the host places a small amount of green tea powder into the bowl, adding the appropriate amount of hot water. The host then mixes the tea with the chasen using strictly set movements. When the tea is ready, an assistant may bring it to the guests or the guests may come and take the tea for themselves. The guest of honor will bow to the host and the second guest, raising the bowl in a gesture of respect to the host. The guest will then rotate the bowl so as not to drink from the front, utter the prescribed phrase and then may take another sip or two before wiping the rim, rotating the bowl back to the original position and passing it to the second guest with a bow. This process goes on until all guests have drunk from the same bowl, which is then returned to the host. There are some ceremonies where guests may have individual bowls, but the process and order remain the same. When all guests have had tea, the host will clean the utensils to prepare them for storage. At this time, the guest of honor may ask the host if the guests may examine the utensils; these are handled with extreme care as may be irreplaceable heirlooms and are often handled with a special cloth.

Although not everyone’s cup of tea, it is a special occasion to even view a tea ceremony much less be asked to participate and if a chance comes along, this ancient ceremony is well worth seeing first hand.

Story by James Souilliere

From J SELECT Magazine, November 2008

Recent Comments