With the scarcity of vegetarian (not to mention vegan) food in the majority of mainstream Japanese eateries, it may be a little difficult to believe that vegetarian cuisine has a long history in Japan, one which spans back centuries, has deep cultural and religious ties and is still highly respected and revered in select spots nationwide.

The idea of avoiding animal products is one that has been followed by Buddhist monks for countless years, a tradition that has spread throughout Asia to spawn a plethora of variations on the concept. In Japan it is commonly known as shoujin ryori (精進料理), which when translated directly to English means a cooking style that sets you on the path to enlightenment; as shoujin can mean diligence or devotion to a cause, whilst ryori is commonly translated as cooking. Although it may seem like a rather clumsy translation for “vegetarian food,” the history behind the cuisine, and perhaps more importantly, where it is most commonly served both add a sense of grandeur and purpose to shoujin ryori, as if you truly want to appreciate it in its true glory and authenticity, you may have to visit a Buddhist Temple.

The very foundation of shoujin ryori is based upon the idea of “Ahimsa” an ancient Buddhist Sanskrit, which encourages peace over violence; as the “a” translates to “without” whilst “himsa” means “injury.” The concept is so old, it spans a number of cultures, from the varying Buddhist traditions of different nations, to Hindu and Jainist beliefs. But no matter where it is practiced, deploring violence is always its central message, so that meat of all kinds, fish and diary products are often excluded.

In Buddhist teachings, it is believed that every living thing shares a communal life force, so that if you hurt another you are in turn hurting yourself. This is such a fundamental belief, that it does not only extend to animals, but plants as well. On face value this may seem like all fruits and vegetables would also be seen as taboo ingredients, but the rule only applies to bulbs or root vegetables, as when they are unearthed, the plant is effectively killed. So carrots, onions, potatoes and standard Japanese ingredients such as daikon or renkon are normally not used in truly traditional shoujin ryori dishes.

Besides all of this, the strict sense of restraint and abstinence from stimuli found in Buddhism also plays a part in many recipes, as ingredients that excite the palate, such as ginger or green onions, common garnishes in Japan, can be excluded altogether. Spices are also avoided, which not only means that the true taste of every ingredient is not masked, but also that they are not preserved, so that every aspect of the meal is extremely fresh by necessity.

Even with all of these restrictions, the format for the meal is rather familiar to anyone familiar with Japanese cuisine. Rice or noodles are most commonly the central carbohydrate provider and the true base of the meal, whilst tofu is also used on a very regular basis, stepping in for the fish or meat side you may normally expect. Several side dishes of fresh vegetables are normally provided and they may be fried, served as tempura, or boiled. Soups are also used on a regular basis and can be either miso, or a delicate vegetable stew. Besides all this, a desert of freshly cut fruit will accompany the meal, meaning you will have over half a dozen dishes to enjoy.

What makes shoujin ryori so appealing to such a wide demographic is not only its obvious health benefits, but the variation it offers. As the meal is so dependent on fresh produce, the menu will change to accommodate seasonal goods, meaning that the time of year when you decide to partake in shoujin ryouri will have a direct impact on what you can expect to be served, and visiting the same restaurant at different times of the year will mean that you can enjoy an altogether new experience.

The subtle flavors of Shoujin Ryori are matched perfectly with the relaxed and gentle atmosphere you will often enjoy it in. In Tokyo for example, you can indulge in two very different approaches; you could for example visit Rankan-tei (http://www.rakan.or.jp), which has a large communal room that can be hired out for private parties, but is more commonly used so that all customers can enjoy a more social meal. On the other hand, Daigo (http://www.atago-daigo.com) offers a more sophisticated atmosphere, with several private tatami rooms adorned with traditional Japanese low-tables, as well as a carpeted room furnished with Western style tables and chairs.

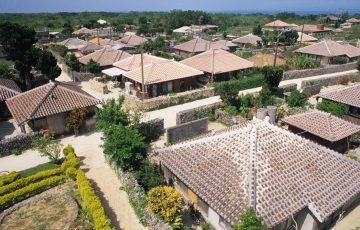

If you are willing to look a little further afield, there are locations nationwide that offer a night’s accommodation, a dinner and breakfast in the shoujin ryori style and full access to the long-standing Buddhist culture. One of the most renowned areas of Japan for spirituality and perfectly preserved history is Mt. Koya in Wakayama prefecture, the home of the legendary scholar and philosopher Kobo Daishi.

Not only are there countless memorials built to honor Kobo Daishi, but as the remote town was all but unharmed by the second world war, you can also see some of the oldest buildings still standing in Japan, such as the Fudodo, which was originally built in 1197. There is also a plethora of temples to visit, 52 of which offer up their grounds for the public to use as lodging. Out of all of the available temples to visit, Rengejoin has been awarded 3 Michelin Stars and is seen as the best of an amazing bunch. They pride themselves on their Goma-Dofu, a tofu that is made with a sesame base, and is a little firmer and denser than your average bean curd.

Not only are there countless memorials built to honor Kobo Daishi, but as the remote town was all but unharmed by the second world war, you can also see some of the oldest buildings still standing in Japan, such as the Fudodo, which was originally built in 1197. There is also a plethora of temples to visit, 52 of which offer up their grounds for the public to use as lodging. Out of all of the available temples to visit, Rengejoin has been awarded 3 Michelin Stars and is seen as the best of an amazing bunch. They pride themselves on their Goma-Dofu, a tofu that is made with a sesame base, and is a little firmer and denser than your average bean curd.

But no matter where you enjoy shoujin ryori, enjoy it you will, as the food, the history, the culture and local community are all entwined into one experience. Whether you choose to indulge in an evening meal, or immerse yourself completely in the culture of the food and stay in a temple, shoujin ryori is the perfect escape from the stress and daily grind of cosmopolitan life, as it whisks you back to simpler and quieter times. The tastes are as delicate as the culture and they should both be absorbed, enjoyed and savored.

By Adam Miller

From WINING & DINING in TOKYO #44

Recent Comments