Playing one of Krush’s CD’s is a blissful journey of soundscapes and experimental juxtaposes all smoothly blended together in a smooth mix of vocals, soul textures, rapping, beats and live instrumentation.

Playing one of Krush’s CD’s is a blissful journey of soundscapes and experimental juxtaposes all smoothly blended together in a smooth mix of vocals, soul textures, rapping, beats and live instrumentation.

His hybrid and genre defying music is vastly experimental, and his ability to exquisitely fuse his stated influences of jazz, old techno, house, rock and reggae, has made him one of the biggest names in abstract hip-hop.

Crowned the proverbial king of Japanese hip-hop, and a much sought after turntablist, his impeccable skills on the decks have impressed crowds all over world.

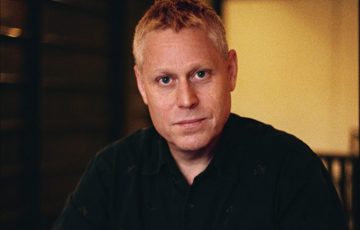

Meeting Krush, on an unbearably hot summer afternoon in a CBD hotel lobby, he is relaxed, improbably full of downtown humor, laced with a relaxed groove that makes you warm to him instantly.

In stark contrast to his on stage demeanor, where he manipulates the decks with a look of intense concentration, reflective of a downtown artisan tending to his craft, he is quite chatty, charming and jests incessantly with a kind of shitamachi humor.

Catching him in the middle of a world tour, it is evident DJ Krush is enjoying his immense popularity which had its humble beginnings at a Tokyo cinema.

It was there that the then teenage Krush become enamored with hip-hop after watching old school godfather Grandmaster Flash in the American film “Wildstyle,” with its gritty street aesthetic, fraught with subway shots, breakdancing, and freestyle MCing.

“I really liked music, and was in a band in junior high school, but I couldn’t find the type of music I really wanted to do. When I saw ‘Wildstyle,’ it utilized things you could find at home, like a turntable and records, and my father had records, so, it seemed like something I could do straight away. And I could get a real feeling of the streets off it.”

In 1987 he formed the Krush Posse, which quickly gained notoriety, and was at the time considered the most successful hip-hop group in Japan. The outfit disbanded in the early 90s, at which point Krush started to pursue his solo career.

Krush is a pioneer in Japanese music, being one of, if not the first, person to use decks as a musical instrument in Japan, doing free sessions with musicians on stage, having started 20 years ago–when finding information about DJing was hardly as easy as going to a DMC course and enrolling.

“There was absolutely no information those days, and now there are things like DJ schools! There was nothing like that, so I bought the video, and watched on repeat a multitude of times the DJ scratching and tried to figure it out like that. That was how I learned… While you could buy mixers at the time, you couldn’t buy what they were using in ‘Wildstyle,’ so I ended up buying something totally different, I remember really struggling with it.” Reflective of his experience, his beat mixing is pure mastery. Watching the maestro live is mesmerizing as he meticulously connects disparate breakbeats, and his sublime scratching skills have earned him monikers like “Zen master” when he plays to packed clubs all over the United States and Europe and festivals such as Sonar in Barcelona where he headlines.

However, beyond turntablism, he has cemented his importance in the Japanese hip-hop landscape as a producer with his composing skills. His debut “Krush” was released in 1992, and was then quickly followed by the immensely popular “Strictly Turntablized” on trip hop stalwart James Lavelle’s Mo Wax label. He has also released albums through Colombia and Island, and was signed to Sony in 1999.

His productions are down-tempo, mood shifting, texture heavy journeys, and are heavily sampled. And, having a fondness for collaboration, there are a number of heavyweights on his albums such as DJ Shadow, Guru from Gangstarr, Mos Def, DJ Kam, MC Black Thought, drummer Ahmir Guestlove Thompson from the Roots, Nigerian percussionist Tunde Ayanyemi, and Company Flow.

He has remixed everyone from Miles Davis, and James Brown to Osaka noise outfit The Boredoms, and has worked with Cold Cut and DJ Vadim. His most memorable tracks also feature sultry female vocals from the likes of Zap Mama, N’Dea Davenport (of the Brand New Heavies) and Deborah Anderson.

His titles usually consist of one Japanese word, and his sleeves have artwork by legendary NY graffiti artist Futura2000 and British designer Ben Drury, and his music videos are beautifully directed. To Krush, these are fundamental elements to his work as well, which makes the MP3 revolution all a bit lamentable to him.

His titles usually consist of one Japanese word, and his sleeves have artwork by legendary NY graffiti artist Futura2000 and British designer Ben Drury, and his music videos are beautifully directed. To Krush, these are fundamental elements to his work as well, which makes the MP3 revolution all a bit lamentable to him.

“There are so many places you can download music now,” DJ Krush sighs. “One thing that is a shame is that you can download a single track from an entire album. If it’s a file, it’s not like it is tangible, like we really consider the CD jacket and the jacket of the vinyl part of the product. When the file gets downloaded, yes, you can also download the jacket, but it’s so small, and you can’t hold it, so there is definitely that feeling of sadness.”

Also, mentioning that he often stays up all night in the studio just to perfect the sound quality of his recordings, the fact that most songs are now being played on computer speakers is a somewhat depressing reality.

“You really can’t hear the benefit of that at all. There are some Japanese that listen with their cell phones, with that tinny noise, it’s really a pity. There is that characteristic warmth of analog, and that sound can’t be replicated by digital. I think of it as a different thing. From the perspective of someone that makes music, it’s a bit sad. But it’s also convenient. It’s a really complicated feeling.”

The salient thing when talking to Krush is that he is immensely humble, suggesting that after two decades, he is “still looking for his own style.” His is renowned for having a modest attitude that is in contrast to much of the hip-hop world that is fraught with machismo.

He has an immense respect for music, saying, “It’s a really enormous entity, but probably it’s something that I won’t be able to grasp even up until my death. If you take music away from me, I really am nothing. Just a regular oyaji (old guy).”

Given that music probably saved him from his well documented humble beginnings as a yakuza thug, for Krush, it really is a case of music or nothing, although probing Krush about his nefarious past, (Is it true you were actually a yak?) he guffaws into his glass.

“Oh, man! Are you for real?! Well it’s more like I was a thug…but I thought it would come up in conversation. It was when I was young, and doing bad things all the time. I couldn’t find what I wanted to do, and by doing bad things, I guess I was affirming that I was alive.”

But asking if it was all just “bad things” or if the street life had a positive influence on his life now, Krush reflects, “The honorifics and hierarchy in that world is really quite extreme, and it has nothing to do with age. Also they do have that notion quite strongly that if you are going to do something, not to get beaten by anyone and rise to the top. So those aspects from that world I have drawn from, and I think it’s the notion that I have to find something that only I can do. If I’m going to do it anyway, [I should] to try and get to the top. Aside from that, it’s all bad things though,” he adds with a laugh. In order to rise to the top, Krush had to innovate, thus his work is heavily experimental. Japanese culture is notorious for “borrowing,”–importing, re-appropriating, and making things viable for their own culture and environs–rather than strictly innovating. Japanese hip-hop is no different, and initially suffered through an embarrassing era of simply mimicking America. Japanese rappers would completely dismiss the reality of their socio-economic background and rhyme about ghettos and racial disparities.

“Well, initially hip-hop was a culture that was born in America, right? So [Japan] was imitating that. As the years went on, people started developing a sense of originality, an individuality that only they had. Not only DJs, but also rappers who were rapping in Japanese, and reflecting on things that were actually happening in their own country, not just copying gangs with guns.”

There are still lots of them that are still just copying, but as DJing becomes an industry and the scene becomes bigger, the number of people involved has increased, too, which means it’s not acceptable to just do the same thing. So there has been an increase in DJs that want to manifest their own individuality.”

This has meant that gradually the hip-hop scene has taken a local flavor, and developed musically, adding intensity and integrity to the local scene, even if this means ditching the weapons laden lyrics to waxing about cell phones and cute girls. This can be seen in not only the music side of hip-hop, but with other elements of the culture such as graffiti as well.

Indeed listening to Krush’s music, there is an intrinsically Japanese vibe to it, although he insists, “It’s not on purpose, I guess it comes out naturally like that, and that is the way it is perceived. ” However unintentional it may be, whether it’s by use of traditional instruments such as the shakuhachi, or koto, as with the filmic album “Jaku,” or by using Japanese rappers, there is a definitive Eastern vibe to his tracks.

For Krush, who is usually on tour for about a third of the year, he says when he first went overseas he wasn’t really conscious of his “Japaneseness,” but gradually his heritage is something that has become harder to ignore.

“At first I was oblivious to it, but as I go to more countries, I really think, ‘I really am Japanese,’” explains Krush.

The more I talk to Krush, the less he seems like the otherworldly scratch maestro with an esoteric public persona and stage presence, and it is just as easy to see him fishing, or riding his bike through the rice fields of his hometown in Nerima, with sake stuffed in his pocket–a pastime that he cites as a “hobby.”

Admitting that he prefers the countryside to the city, he even goes as far as to recommend the country, rather than go to really large cities, with their sweet grandmas and grandpas, and their low tension vibe. He adds with a chuckle, “It’s so dull! So…dull, but I make music my work, so I seem to prefer the quiet life.”

When not on tour, he says he spends about six hours a day producing, and he says he receives inspiration from everyday things, “When I wake normally, every day the news is changing. Then I’m into fishing, and listening to my kids’ stories, films and photos. And I also get inspiration from the demo tapes I receive from young people, and the new work from other artists. There are so many ways to get stimulated…”

Which brings us to the reality that Krush is indeed a father of two daughters, 23 and 16 years old. And what are the daughters of the world’s coolest father doing?

“The oldest is doing something totally unrelated and the youngest is in high school. And the music they listen to is totally different. The oldest likes rock and the youngest likes things that you see on TV, like Exile and Rip Slyme…” He adds, laughing, “When I go home, that is playing, it’s really quite unbearable.”

They are listening to it cause they like it, so I can’t go home as DJ Krush. If I really went home as Krush, I think my daughters’ CDs would head for the trash bin! I can’t really do that, so I go home as a father, and as a dad!”

Seemingly his wishes for his kids, and the youth of Japan today are to hold on to dreams, above “just existing.”

“There are some kids, when you ask, ‘Do you have any dreams?’ the answer is ‘no.’ ‘What do you want to do?’ ‘I don’t know,’ even if they aren’t that young.”

For Krush, despite his prolific career, he maintains that it is important to not get complacent, and too satisfied, “I really feel grateful to a lot of people that I have been able to come this far. For me to be able to go all over the world is really something I’m happy about, but there is more depth to music, it’s so vast and free. So there is still a lot to pursue.”

And are there any future dreams for this preeminent maestro?

“Well, I’m not that young, so conversely it’s a case of how far I will continue. Like I’ll be going on overseas tours with a cane, and a drip hanging out of me. If there are punters with grandkids who have been listening to me, that is a dream–I would make their entrance fee free…If only I can continue it that far.

Story by Manami Okazaki

From J SELECT Magazine, December 2009

Recent Comments