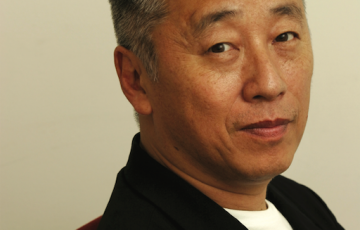

Kosuke Kitajima certainly has presence, so much so that on meeting him my hands unexpectedly shake as I fumble for my business card. It is the way he walks, the way he stands, the way his white Coca-Cola training suit does little to conceal his evident strength Ð an aura totally at odds with his smiling courtesy as he bows his hello.

Kosuke Kitajima certainly has presence, so much so that on meeting him my hands unexpectedly shake as I fumble for my business card. It is the way he walks, the way he stands, the way his white Coca-Cola training suit does little to conceal his evident strength Ð an aura totally at odds with his smiling courtesy as he bows his hello.

Even his friends say he has two characters: Kitajima the champion breaststroke swimmer, 100 percent focused on the task in hand, and Kitajima the joker, “the same as any other guy… the fun guy.” Or at least, “that’s what people around me say, but I have never been particularly conscious of any difference… I’m very easygoing.”

Kitajima became a symbol of national pride after breaking the world records and becoming world champion in both the 100-meter and 200-meter breaststroke long course events at the Swimming World Championships in Barcelona in 2003, and, then, blowing his rivals out of the water, winning the gold medals for both events in the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens as well.

A competitor also in the 50-meter breaststroke and medley events, Kitajima has been swimming since the age of five. At the time of writing, he is preparing for a European grand prix that will see him compete in several countries across the continent.

He is not really sure who his opponents will be as this is a mere preliminary for the summer’s International Swim Meet. It is an opportunity to “fine-tune my condition,” as he puts it. “The best way to beat pressure is by training as much as possible and by focusing on raising your ability as much as you can rather than thinking about opponents.”

Swimmers become successful at a very young age, and Kitajima is a case in point: world champion and world record holder at 20, and Olympic champion at 21 Ð which means now, aged 24, Kitajima is practically a veteran. He will be 25 at the next Olympics in Beijing so surely there is at least a little concern about how will he fare against his younger rivals?

“Actually, in my events, there haven’t been that many people coming or going in the past four years,” he replies, unfazed. Indeed, worldwide, “the age of the oldest swimmers is rising. But I can’t afford to become complacent. Swimming is a sport where every year the level gets higher.”

And anyway, he adds, “there is a world record that I’m aiming at. Everyone, including me, is heading in the direction of the world record. That attitude is no different between me and the younger swimmers.”Since the dust settled on the gold medals of 2004, Kitajima has struggled to replicate his champion performances.

“I haven’t been able to perform in races as well as I thought I would,” he says, “so I have been training concentrating on the thought that this year I will perform to my full potential.”

So far, the training seems to have paid off and Kitajima successfully defended his 200-meter world championship title in Melbourne earlier this year. Nevertheless, for Kitajima, that is not enough.

“Although I won a gold medal in the World Championships, I still don’t feel that I have returned to top form,” he says.

Yet already with a sack of gold under his belt and being one of Japan’s all-time most successful swimmers, there is surely little left to achieve.

“At the moment, my position is not the world number one and I do not have a world record. I want to be the world record holder and I want to stand again at the highest place in the Olympic Games,” he says firmly. “That’s all. I’ve heard before about having everything and that that’s enough, but I am not satisfied.”

Having risen so high in his field (or pool, rather), the Tokyo-born breaststroke swimmer is subject to the same intense scrutiny that other athletes on the international scene receive from the local media.

Having risen so high in his field (or pool, rather), the Tokyo-born breaststroke swimmer is subject to the same intense scrutiny that other athletes on the international scene receive from the local media.

“I just try not to think about it,” he says of the attention, even though in this interview he is, again, the center of it. “I try to have things in my mind that are as fun as possible when I am not in the water Ð like going out for a good meal next week or going out to have fun after this competition.”

It takes less than a minute to see Kitajima win a 100-meter breaststroke race, and just over two minutes to see him wash out the competition in the 200 meters. But behind it all, for those three minutes of his life, and indeed the spectators’ lives, Japan’s Olympic hero lives a lifestyle itself worthy of a medal: day-in-day-out training for six days a week, from as early as six in the morning to well after dark.

“My day is quite tight,” he begins. “I get up and do some training in the morning from eight, sometimes six. I eat lunch and have a nap, then start again around four until about eight, with two or three hours of that spent in the water; then eat, then sleep. Then it repeats.”

If eating were an Olympic event, Kitajima would definitely be a medal contender.

“I can’t eat a lot before training so I eat bananas, yogurt, bread, something light,” he preludes. “But for lunch, I eat loads, often Japanese food.”

There and then he destroys the popular belief of athletes being calorie-conscious. “I like and eat anything Ð really, anything Ð because I use a lot of calories during training, so I try to consume as many calories as I can,” he says. “Even so, I lose weight.”

Eating is practically a hobby and he enjoys going to restaurants with his friends whenever he can. Nevertheless, he is required to exercise a degree of caution when dining out.

“In my case, eating is also a part of training. Therefore, whatever there is, there’s a lot of it, and I have to eat it all, even when I don’t want to. So it is sometimes uncomfortable to eat. But when I am on a break, I think ÔI am eating properly! Look: I am now really eating what I want!’ Ð this makes me very happy.”

Being devoted to his discipline, it is a wonder he gets any time for himself. Even after training, his relaxation consists of time on the massage table, him being very conscious of caring for his number-one asset Ð namely, his body. And then, after that, it’s an early night. “That’s how the body recovers the most.”

It is on his one-day-a-week off that Kitajima gets to veg out, watching comedy programs and baseball on television. Kitajima likes baseball but has not really played since his school days. In fact, he does not do any other sports Ð not even water sports.

“I can do whatever I want on condition that I won’t be injured,” he says. “I want to do other sports such as baseball or surfing, but there is always the concern of a possible injury so I am asked not to.”

Fortunately, there are no objections to him driving, which looks to be a good thing given the smile on his face.

“I really like driving… It’s one way how I relax.” Kitajima likes listening to hip-hop and R&B when he’s on the road. “I drive all over the place. I often go out eating so I usually drive to restaurants, and other places like… Don Quixote!” he laughs.

When he gets longer breaks, he goes further afield. “It depends on the season, but last time, after the World Championships, I had 10 days off; after the summer competition, I’ll have three weeks. When I get longer holidays, I like to travel Ð either abroad or inside Japan. I like warm places.”Almost as if Kitajima feels at home wherever there is water to dive into, he adds, “I like places where there’s sea, such as Hawaii.”

Kitajima says he also enjoys going out for a drink, although always being in the pool means he has to stay dry. “Before competitions, I quit drinking for about three months,” he says.

Competition or not, Kitajima is a sociable character. He says that swimming aside, what is most important to him are the people around him Ð his coaches and supporting staff, his family and friends.

“I think the world of them,” he says. “I try to spend as much time with my friends as possible, but I don’t actually go out a lot. My friends live nearby so they often come round. Actually, my life is not so colorful. I’m rather hikikomori!” he jokes Ð the word loosely translating as social dropout or failure, with connotations akin to otaku.

Appropriately, it turns out that his current maib-oom, or “my boom” Ð thing-of-the-moment Ð is a Nintendo Wii game console. “I don’t usually play games and I was not allowed to play when I was younger, but I like games on the Wii because friends can play together.”

As there is little risk of injury, this is how he gets to play baseball, tennis and the like Ð and as a breather from day-to-day life, he confirms that he does not have a swimming game.

Even if he had a swimming game it is difficult to imagine him playing it on his day off.

“I do sometimes get bored with having to train all the time,” he says. “But I really like competitions. I can bear the hard training sessions due to the excitement I feel for competitions… The bigger the competition, the more excited I get.”

For such a person, competing on the world’s biggest stage must be a blast. “I absolutely love competing at the Olympic Games. I have such a strong desire to challenge there.”

Making events particularly exciting for spectators are the attendant rivalries, and drawing the crowds to swimming is the rivalry between Kitajima and US counterpart, Brendan Hansen. Over the years, the two have persistently stolen each other’s show, with Hansen taking one of Kitajima’s world records just before the Olympics, and Kitajima extracting revenge by winning the gold medals in both their specialist events Ð Kitajima’s 100-meter gold being on none other than Hansen’s birthday.

Making events particularly exciting for spectators are the attendant rivalries, and drawing the crowds to swimming is the rivalry between Kitajima and US counterpart, Brendan Hansen. Over the years, the two have persistently stolen each other’s show, with Hansen taking one of Kitajima’s world records just before the Olympics, and Kitajima extracting revenge by winning the gold medals in both their specialist events Ð Kitajima’s 100-meter gold being on none other than Hansen’s birthday.

Yet for all the times they have faced each other, they cannot communicate Ð a feature of their rivalry often alluded to in after-race interviews when one or the other comments that neither can speak the other’s language. Preventing them from establishing a social relationship, this only serves to heighten the tension. “We are rivals, there to compete, so I don’t think we could have fun conversations anyway,” Kitajima says. “Plus, silent intimidation is important.”

The polar opposite of the New Zealand rugby team’s haka (traditional Maori dance), this approach seems typically Japanese.

“As I don’t speak English, I don’t understand what they say and so I sometimes feel pressure,” he adds. And yet it must be the same the other way round. “It’s a strategy Ð not letting your opponents know what you’re thinking.”

Having said that, he continues, “I do think that if we spoke each other’s language, I would find swim meets even more fun Ð not just to talk to Hansen, but also with other swimmers.”

Spending more time abroad than the average Japanese, he does feel the desire to learn another language. “But I don’t like studying!”

Kitajima has no idea when he will quit swimming, but when he does, he would like to have a crack at English Ð by which time, his profession will be…

“I haven’t decided yet. Nothing physically hard.” Predictably, and with a smile of anticipation, he says that his experiences have given him an appetite for a somewhat different life.

Story by Manami Makiko Sugiura

From J SELECT Magazine, August 2007

Recent Comments