One of the poorest prefectures in Japan, Miyazaki has been undergoing quite a makeover in both its economy and image, largely due to the public relations skills of its energetic governor, a flamboyant ex-comedian. An old honeymoon spot for Japanese back in the 1950s and sixties, Miyazaki had degenerated into a decidedly un-cool place by the 1980s, a trend reflected in its slipping tourist revenues. However, visitors are now taking a fresh look at the prefectural capital—with a younger crowd drawn to it’s beaches, surfing conditions, hotels, cafes and amusement arcades—patronizing small resorts like Aoshima during the spring and summer months.

One of the poorest prefectures in Japan, Miyazaki has been undergoing quite a makeover in both its economy and image, largely due to the public relations skills of its energetic governor, a flamboyant ex-comedian. An old honeymoon spot for Japanese back in the 1950s and sixties, Miyazaki had degenerated into a decidedly un-cool place by the 1980s, a trend reflected in its slipping tourist revenues. However, visitors are now taking a fresh look at the prefectural capital—with a younger crowd drawn to it’s beaches, surfing conditions, hotels, cafes and amusement arcades—patronizing small resorts like Aoshima during the spring and summer months.

Just a few stops down the coast on the delightful, two-carriage Nichinan line train from Miyazaki, few tourists take the trouble to continue on to Obi, an old samurai town with some genuine historical credentials. Little publicized or written about, it is possible that even in tourism-driven Japan, few people know of its existence. A quick survey among Japanese friends and neighbors failed to get even a glimmer of recognition at the name. Obi’s obscurity is not altogether surprising given that the town is tucked away on the Udo headland, part of the Nichinan Coast, but an inland segment without the draw card of beaches and sea. For those with an interest in heritage, this is more a blessing than a defect.

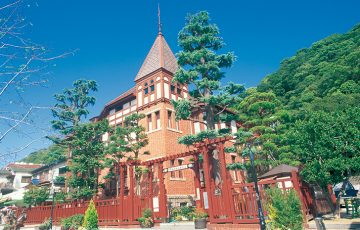

Sensing that the fringes of old towns can yield as much as their listed cultural sights, I opted to follow one of the lanes that runs parallel to Obi’s main street, route 222, where the backstreets languish in a time slip of traditional houses, old samurai style villas, and meticulously kept gardens. Stone walls and carefully crafted topiary ensure privacy, while offering restricted but tantalizing glimpses of cycad clumps, well tended lawns, rock arrangements and weathered stone lanterns. Among traditional Japanese wooden houses, with their dark tiled roofs and spacious decks, are a few Meiji era Western-style residences. Their light blue, clapboard walls, louvered windows, and iron lanterns evoke the diplomatic residences of old foreign port settlements like Kobe.

Look closely enough along these lanes and you may even see vestiges of a feudal structure sustained to the present by an imbalance of wealth. At the end of one lane near the station, a row of corrugated iron and wood houses stand facing the river. Reminiscent of Victorian almshouses or charity homes, their open doors reveal a tiny entrance area and a single, four-tatami room with a sink and small gas range jammed into one corner. Contrasting these hovels with villas owned by the of descendents of samurai and highly placed officials, the outline of a social order no longer enforced but still partially observed, emerges. Reinforcing the sense of time standing still are forest shrines on the outskirts of the town, sanctuaries of peace tucked behind thick stands of Obi oak, cryptomeria and cedar. The moss covering the ancient stone steps leading up to these sacred places is only faintly trampled, a measure of how little visited these sacred spots are. Not that Obi is completely neglected by visitors. A small number of discerning Japanese travellers are seen passing through the grounds of gardens and villas, stopping to admire the roadside conduits of clear water, home to large, colourful carp, or to stop at one of the teahouses along the main street for powdered green matcha, Japanese sweets, or obi-ten, a mix of tofu, flying-fish and miso, which is the local specialty.

A car park near the castle remains (large enough to serve a couple of tour buses) to support a souvenir shop and a few vending machines, hinting at seminal tourism facilities discreetly set back from the historical buildings themselves. You can even take a rickshaw ride through the town. Unlike the Nanzen-ji area of Kyoto or the downtown quarter of Asakusa in Tokyo, with their dozens of rickshaw men, Obi has only one puller, a cheerful fellow who will provide an interesting “running” commentary on the town’s modest but endearing sights, sprinkling history and arcane details about landscaped gardens with local tales and legends. If the rickshaw seems an odd choice of conveyance for Japan, one more readily associated with the crowded streets of Dhaka or Lahore, it should be remembered that this unique form of transport was a Japanese invention, making its first appearance in the Nihonbashi district of Tokyo in the 1860s.

A car park near the castle remains (large enough to serve a couple of tour buses) to support a souvenir shop and a few vending machines, hinting at seminal tourism facilities discreetly set back from the historical buildings themselves. You can even take a rickshaw ride through the town. Unlike the Nanzen-ji area of Kyoto or the downtown quarter of Asakusa in Tokyo, with their dozens of rickshaw men, Obi has only one puller, a cheerful fellow who will provide an interesting “running” commentary on the town’s modest but endearing sights, sprinkling history and arcane details about landscaped gardens with local tales and legends. If the rickshaw seems an odd choice of conveyance for Japan, one more readily associated with the crowded streets of Dhaka or Lahore, it should be remembered that this unique form of transport was a Japanese invention, making its first appearance in the Nihonbashi district of Tokyo in the 1860s.

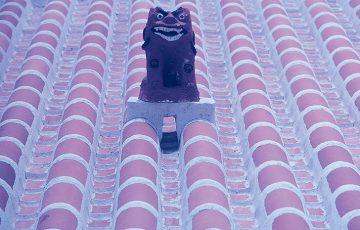

In Japan, people usually talk about the old and new sections of towns as distinct areas. In the case of Obi its safe to say that, with the exception of some of the more recent additions to the immediate station area, it’s all old. The car-parking zone is a good place to start a perambulation of the core historical town. Right next to the lot is an archery range of the kind occasionally found in shrine and temple precincts. Archery galleries located inside tents set up in the grounds of large shrines and temples during the Edo period, sometimes served as thinly disguised dens of prostitution. The cultural credentials of Obi’s archery range are unimpeachable, though. Known as shihanmato (meaning ‘four and a half’), the name refers to the repetition of the number four during the shooting, and the bow and target distances according to a system of counting, where things were measured in ken, shaku and sun. The scheme was carefully explained to me in the simplest of Japanese, but I can’t say I was any the wiser at the end. It’s probably best to just watch and learn from the elderly archers who are on hand to help. A small booth beside the range dispenses tickets, after which you remove your shoes, sit on tatami mats set above an area of gravel leading to the target.

The Ito clan ruled Obi for a full 14 generations, helping to confer on the town a deep sense of cultural and social continuity right up to the Meiji Restoration of 1868, when the castle was abandoned. The remains of the fortress, including its tastefully restored entrance gate and original walls, lie just around the corner from the archery range, but there are one or two sights worth stopping at beforehand.

Forced to vacate the castle and its association with a feudal system now supposedly replaced with an age of cultural enlightenment and modern governance, the Ito family and a remaining handful of retainers moved into the Yoshokan, a spacious wooden villa with a well maintained Japanese garden. From the rooms of the villa there is a superb ‘borrowed view’ of Mount Atago in the distance, nicely framed by paper screens. A completely authentic building, one that has been maintained but not altered, all the rooms of this airy structure face south in accordance with the rules of geomancy. It’s a fine, well-appointed residence that feels both graceful and somehow bucolic. A similar, though far smaller garden can be found at the nearly Denzaemon Ito House, the former residence of a high-ranking samurai. The house was built from Obi cedars, which contrast nicely with the stone foundations of the building and rock arrangements in the small garden.

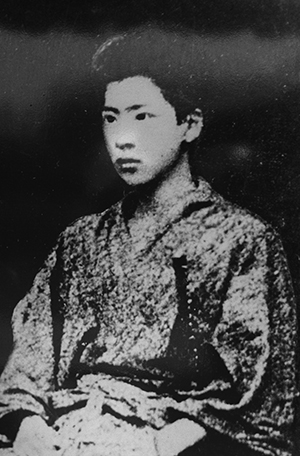

Obi’s best known figure in the modern era was Jutaro Komuro, son of a local samurai whose ambitions propelled him through the transitions of the Meiji period and its abolition of feudal customs. The Memorial Hall is a house and exhibition hall containing personal effects, documents and videos on the life of the diplomat Marquis Jutaro Komuro as he was known to Western diplomats eager to have a title with which to address the young man. Known as the signature of the Treaty of Co-operation with the United Kingdom at the beginning of the 19th century, he also served as the Ambassador Plenipitentiary for a delegation sent to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, for the Peace Treaty Conference. Komuro is also known for obtaining a revision of the Unequal Treaties act and for restoring Japan’s sovereignty on customs rights, no mean feat for a Meiji period diplomat. Nichinan City, of which Obi is a part, became the sister city of Portsmouth in 1985. The school Komuro graduated from, a remarkably well-preserved building dating from 1831, lies a few minutes east of the castle gate. A peaceful place surrounded by lawns and pine trees, stern discipline must have prevailed at Shintokudo (Fief School), as it was established exclusively for the sons of Obi’s samurai families.

Obi’s best known figure in the modern era was Jutaro Komuro, son of a local samurai whose ambitions propelled him through the transitions of the Meiji period and its abolition of feudal customs. The Memorial Hall is a house and exhibition hall containing personal effects, documents and videos on the life of the diplomat Marquis Jutaro Komuro as he was known to Western diplomats eager to have a title with which to address the young man. Known as the signature of the Treaty of Co-operation with the United Kingdom at the beginning of the 19th century, he also served as the Ambassador Plenipitentiary for a delegation sent to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, for the Peace Treaty Conference. Komuro is also known for obtaining a revision of the Unequal Treaties act and for restoring Japan’s sovereignty on customs rights, no mean feat for a Meiji period diplomat. Nichinan City, of which Obi is a part, became the sister city of Portsmouth in 1985. The school Komuro graduated from, a remarkably well-preserved building dating from 1831, lies a few minutes east of the castle gate. A peaceful place surrounded by lawns and pine trees, stern discipline must have prevailed at Shintokudo (Fief School), as it was established exclusively for the sons of Obi’s samurai families.

At the core of the old quarter, the stone and plastered Otemon, or main gate, forms the main entrance to the castle grounds. Destroyed in 1870, only its walls, carefully reconstructed in the original style using joinery rather than nails, and a whitewashed history museum, remain. Climb another flight of steps deep within the castle precincts, though, and you will come across the Edo period Matsu-no-Maru, the residence of lord Ito’s most senior wife. Judging from old prints of the original, it’s a faithful replica, replete with women’s quarters, reception rooms and the Gozaemon, a beautifully stark tea ceremony room. As the private sanctum for the family, it must have been a very pleasant place to live, if the mushiburo, a steam bath with a clay stove just visible behind a Chinese gable, is anything to go by. After exiting the bath, the family could then cool off in a small tower designed to catch the evening breezes. Such were the benefits of privilege.

Returning to the main street, better known as Otemon-dori, and the walk back to the station, you sense that this former castle town, like other fortress towns throughout Japan, was both a military and commercial center, a view corroborated by several fine, whitewashed merchant houses strung along the road. In a country with such a weak preservation ethic, the best chance a building has of survival is to give it a function. Many of these solidly built but gracious Edo and Meiji period homes are now serving as stores, small museums and restaurants.

Besides the prescribed sights marked on the map that comes with the collective ticket to the main spots available at the station or any of the town’s sights, the real pleasure of Obi is to wander impulsively along its silent streets, peering into stone gardens, bordered by sub-tropical plants, sago palms and plantains, discovering in the process old weathered and timbered buildings that in any other country would be listed properties. Obi’s secret perhaps, is that it has found a continuing purpose for these buildings and, while welcoming a modest level of tourism, remains firmly outside of the mainstream.

TRAVEL INFORMATION

The limited express Nichinan line train via Aoshima, takes about 65 mins. to cover the 50km to Obi. There are also buses from Aoshima and Udo-jingu. The main town is about ten minutes walk east of the railway station. Bicycles can be rented from the station kiosk for ¥300 for three hours, but you will see more on foot. Miyazaki is a good base for exploring this region. The station has a small information booth with good local maps. Satsuma-so, a modest, traditional style inn is good value and friendly at 3-6-9 Ota (Tel: 0985/ 51-4488). Hotel Kensington, a smart, efficiently run business hotel, has cheerful rooms for as little as ¥5,500, all with en suite baths. Obi-ten Chaya is a pleasant old-fashioned restaurant along Ote-mon-dori that serves a number of cheap dishes, and obi-ten.

Story & photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, June 2008

Recent Comments