“Where are you from,” she asked.

I thought about where I was from and lit a cigarette. That place colored by associations with tattoos, the jabisen, and ways as strange as ornamental designs.

“Very far away,” I answered.

A Conversation, Yamanokuchi Baku.

Once a place natives of these islands were reluctant to claim as their own, Okinawa is now a much admired land of ancient wisdom, good health, sweet island songs and the occult rites of mystic, white-robed shamans known as yuta. [To be honest, I’m still not sure if yuta are mystic, white-robed shamans. Is this correct? Otherwise perhaps remove the reference to yuta altogether and end with … “mystic, white-robed shamans.” I found yuta to be a bit confusing when placed before the description…]

Blending with the blue waters of Okinawa’s remotest islands, the Yaeyamas, fragments of Southeast Asia and China, loosened and detached, have floated north on the plankton-rich currents of the kuroshio, Japan’s “black stream.” On islands less visited, the leitmotif of this archipelago is the lilting sound of the jamisen, a snakeskin version of the mainland shamisen, an instrument whose voice is alternatively festive and melancholy, seeming to hail from more exotic regions to the south.

The Yaeyamas, along with Okinawa’s better-known islands to the north, were incorporated into the Liu-chiu Kingdom during its early 15th-century expansionist period. Under the later suzerainty of both the Satsuma domain of Kagoshima in southern Kyushu and as a vassal of China until 1872, the southern islands location in the South China Sea, further from Tokyo, or even Kyoto, than Taipei, allowed it to assimilate both Chinese and Japanese influences simultaneously. These remote islanders have also been influenced by Southeast Asians, allowing for other, more exotic influences to creep in. Malay–style turbans, for example, were sported throughout the islands after they became popular towards the latter part of the 19th century.

After the direct annexation of the islands by Japan in 1879, however, attempts were made by the authorities to implement a systematic process of Japanization. Despite obvious parallels in social organization, similarities in religion, linguistic ties and a combination of geographical isolation and the survival of robust traditions have helped resist efforts by Tokyo to completely remodel the islands and draw them into the cultural mainstream. Commenting on the limits of Japanese acculturation in the region, William Leda notes in his book, Okinawan Religion, “there has been an ebb and flow of contacts through the centuries, not a continuous and unilateral interaction.”

Being out of the mainstream has benefited these islands in a number of other ways. The Yaeyamas were fortunate enough to be left comparatively unaffected by Japanese colonial policies of the past century and to have come out of the pitched battles of World War II and the effects of the subsequent American occupation of Okinawa, which only ended in 1972, relatively unscathed. A planned invasion of Miyakojima, an island to the north of the Yaeyamas, as part of the Battle of Okinawa, was abandoned, it seems, after strikes from Allied aircraft carriers effectively immobilized its five large airfields.

Even during the American occupation of Okinawa, the people of the Yaeyamas experienced very little contact with military personnel. Although mass tourism and the presence of US military bases (what David Scott describes in his book Samurai and Cherry Blossom, as the onslaught of the world’s two “most pervasive cultures, America and Japan, Kentucky Fried Chicken parlors alongside sushi bars; conformity spiced with vulgar individuality”) have unquestionably devitalized mainland Okinawan culture, the Yaeyamas have fared rather better.

The name Yaeyamas can be translated literally as “eight mountains,” a description that, quite rightly, suggests the presence of large and highly visible rock deposits. Ishigaki is the main island of the Yaeyama archipelago and its administrative center. Its name signifies “stone walls,” a derivation from the local dialect “ishiagira”, meaning “a place of many stones.” Its airport and harbor serve the other outlying islands in the group. Ishigaki offers visitors more creature comforts than are normally found on the other islands and a larger number of conventional sights, but also makes an excellent base from which to explore islands whose names and locations are unfamiliar even to many Japanese people. It is here in many respects that the real Okinawa and the mélange of influences that have given the islands their own distinctive character can be found.

Ishigaki’s island feel is intensified by the roadside presence of colorful dugout canoes, more suggestive of Polynesia than Japan. The aquatic side of the Yaeyama’s history and evidence of its intermingling with other cultures can be gained by a walk along Ishigaki’s western shore, where it is still possible to find shards of ancient ceramic wares carried by Chinese trading vessels 400-500 years ago. Damaged or broken objects are believed to have been deliberately thrown overboard, or to have been washed ashore from shipwrecks. More samples of the islands’ unique culture can be seen at the Shiritsu Yaeyama Museum, where good examples of ancient Panori ceramics, Yaeyama-jofu textiles and canoes can be found. The Yaeyama Minzoku-en has an interesting exhibition on the history of the islands’ weaving styles.

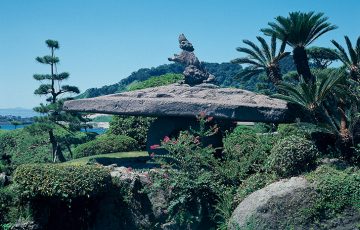

Also of interest in the town itself is the beautifully preserved Miyara Donchi, the ancestral home of the Matsushige family. Modeled after aristocratic buildings at the royal capital of Shuri in Naha, it is the only such house left in Okinawa. Built in 1819, its stone garden, made from pitted coral in the Chinese manner and sprouting with myriad tropical plants, sets it far apart from mainland Japanese dry landscape arrangements.

The island is also of considerable ecological importance. Besides the immensely important Shiraho Reef – the world’s largest, and finest, example of blue coral – Kabira Bay on the north coast is another little known gem of this island. Here, small islets rise like loaves of bread from steeply shelving emerald waters. A sign on the beach warns against swimming but this is understood by locals to be a deterrent to tourists; the bay, in fact, is home to a modestly lucrative cultured black pearl industry. Artificial irritants are inserted into oysters growing in underwater cages. These produce black and gray-tinted pearls of considerable beauty.

Yaeyama cuisine, with its rich lashings of seafood and pork, speaks of different culinary preferences from the mainland. Snake meat is said to provide extra physical stamina for both sexes, mimiga is julienned pig’s ear served with cucumber and dressed with vinegar, and the acrid goya chumpuru (sautéed bitter melon with egg and pork) is an acquired taste that is now eaten all over Japan. All said dishes go well with a glass of invigorating awamori, a distilled liquor made from rice. This particular firewater is said to be the best accompaniment for yagi-jiru (goat stew), another local favorite.

[NOTE::::: As far as I know, goya is bitter melon and goya chumpuru (sp?) is traditionally sautéed bitter melon with egg and pork. Chumpuru is sautéed, and hence you can also have tofu chumpuru, yasai chumpuru and mung bean chumpuru. So I think it’s best to get rid of the mention of your two appetizers, in case the latter (sautéed bitter melon) is confused with goya chumpuru…… does that make sense? I’m a big fan of Okinawan food cos it reminds me of Hanoi food. I’m also a huge fan of goat and snake meat, having eaten them more times than I can recall, though that perhaps might have something to do with the rice liquor consumed with the meal… 😕 ]

Although Taketomi Island can be reached by ferry in under 15 minutes from Ishigaki’s port, it remains, more so than any other island in the group perhaps, a time-capsule among these southern seas, the hospitality of its 400 or so inhabitants a measure of how well it has retained its identity. The name Taketomi signifies “prosperous bamboo,” stands of which can be seen at the roadsides or in the center of this island, whose circumference stretches to little more than nine kilometers.

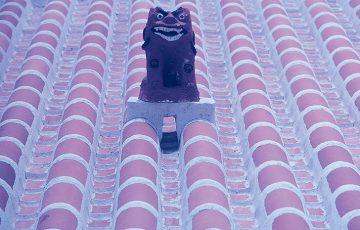

These days the island is noted for its sumptuous flowers and plant life. Taketomi’s tropical blooms owe much to a relatively recent pipeline, which was built to carry water from nearby Ishigaki, replacing a precarious dependence on catchment water. Nature revived and flourishing is one of the delights of this island and a stroll around its sandy lanes hints at the pride these islanders have in their flora. Bougainvillea and hibiscus, traditionally used in this part of Okinawa to decorate graves and Buddhist altars, spill over walls made from volcanic rock, built as a defense against the furious typhoons that strike the islands from late September to early October. Squat, one-story houses stand behind these walls in their neat, sub-tropical gardens, their protective shisha statues placed on attractive red-tiled roofs, which resemble the tuilles roman of southern Europe.

Many Okinawan fabrics that eventually find their way into shops and galleries located in Naha and even as far away as Tokyo are produced by individuals or tiny co-operatives on remote islands few Japanese people ever visit. Taketomi is famous as the source of minsa, an indigo fabric often used as a belt for a woman’s kimono. Minsa is only produced on Taketomi. Strips of the material can be seen drying on the stonewalls of the village.

If Ishigaki is quiet, then Taketomi is a hermit crab. The cleanliness and neatness of the island, which visitors never fail to comment on, stems from an old custom by which it was, and still is, the responsibility of each householder to sweep the street in front of their own property. Large earthenware jars stand against the walls of many homes, a reminder of not so distant times when, because of a shortage of fresh water, it was the custom in Taketomi and other nearby islands like Kuro and Yubu, to divert rain water from roofs into these vessels.

Taketomi’s appealing flora and architecture is best appreciated on foot, though bicycles and 50cc mopeds can be hired from the village stores. These provide travelers with the means to get to Kondoi Misaki, the island’s finest beach. Tiny sea creatures have been fossilized into star-shaped particles to form this beach and, despite the temptation to place them in small glass jars as offerings to tourists, it is still possible to find patches of this rare sand. The stunning coral and aquamarine waters here support variegated tropical fish and other aquatic species, including manta rays, tubby lobsters and game fish. In this respect, Taketomi conforms perfectly to the outsider’s view of Okinawa, a region that provides first-rate swimming and snorkeling. In spring Kondoi Misaki also seems to attract swarms of brilliantly colored butterflies, many as large as napkins.

Once the sun sets in the evening, you can stay at a friendly, plant-bedizened guesthouse located in the island’s solitary village, a place offering the prospect of warm, flower-impregnated nights spent on its salt-worn verandah, listening to the haunting beauty of island music carried from house to house on the sea breeze. It’s a reminder that this may not exactly be terra incognita, but it’s the closest you are likely to get in Japan.

Story and photos by Stephen Masfield

From J SELECT Magazine, July 2005

Recent Comments