In an ecological bid to counter the effects of the concrete jungle, city green space takes to the rooftops.

Tokyoites are likely sweating the summer months to come for good reason. The number of hours that the city broils above the 30-degree Celcius mark has more than doubled in recent years. Temperatures will hang — like the heat, humidity and haze in the air — in the mid 30s for weeks on end. Those who have weathered a few summers here may notice something: It’s getting hotter — by about three degrees in the last century. That’s quadruple the rate of global warming.

While the megalopolis is in a temperate zone, it’s becoming downright tropical. So much, in fact, that tropical plants are even taking permanent root here. But high-altitude explorers, or those with a view, might notice something else: Perched high upon countless urban precipices more green oases are sprouting. Offering shade from the concrete jungle‚s staggering heat, roof gardens are beginning to grow on Tokyo.

“The market for rooftop gardens is expanding at a rate of about 10 percent in the past few years,” says Mitsuo Okada, a representative of Kajima Corp. These days, the large-scale Tokyo-based construction company is building about 15 gardens in the sky annually. “Rooftop gardens are getting attention, not only for their individual affect, but also for improving the living environment in cities such as enhancing scenery and by providing relaxing spaces.” It’s a claim that many are making these days. And bits of bucolic heaven, such as the manicured shrubs, winding walkways and grassy mounds tucked away atop St. Luke’s International Hospital in the city’s Suginami Ward, show that they are not just talking fertilizer.

From government buildings capped with mini public parks and hospitals roofed with gardens for body, mind and soul; to high rises and monumental mixed-use developments crowned with bucolic wreaths, there’s a plot to grow more greenery on Tokyo’s towering tops. And it’s bearing fruit. It’s not just the privileged and — increasingly, the everyday city dweller — that these gardens are meant to shelter from the sweltering sun, but the entire city itself.

Thanks to rapid urbanization, unbridled technology and the ensuing ozone-thinning pollution, the island nation’s capital has itself become an island — a so-called heat island. Ecologists coined the term for a city whose temperature is consistently so much higher than surrounding areas that it stands out in an aerial infrared snapshot like a radiant landmass. With breeze-blocking buildings, countless cars and other heat-generating machinery, the concrete-coated city is making, absorbing and retaining more heat. In a metropolis where peeling back the pavement is as likely as a cool July breeze, rooftop green space is a long-awaited breath of fresh air.

Foliage-covered roofs can be up to 15 degrees cooler than their tarred or concrete counterparts, says a 2000 study by Takenaka Corp., Kyushu University and Nippon Institute of Technology. According to the Organization for Urban Greenery Technology Development, summer temperatures would dip by .84 degrees — saving some 110 million yen a day in cooling costs citywide if half of Tokyo’s rooftops gave the green thumbs up to gardening. While grassy surfaces rarely heat up beyond 25 degrees, flat gravel roofs can reach a scorching 60 degrees. The surge in temperature means air conditioners are turned on — and up — causing power-plant energy output to spike, which in turn produces more pollution. It’s a vicious cycle. The haze and smog trap more heat, piling up the demand to cool things down.

The carbon monoxide inhale, and oxygen exhale plant life provides, however, filters the air. In doing so, vegetation counters the pollution that adds to the city’s greenhouse on a heat-island phenomenon. A 16-square-foot patch of grass, for example, can produce the annual oxygen needed for one person, and 11-square foot of lawn can filter a half-pound of dust particles from the atmosphere during the same period, according to a recent Canadian study. Green space also creates shade, retains moisture and can foster a cooling post-dusk downdraft, according to the Takenaka study. Roof gardens also work as a sponge, easing the burden on a city’s storm water removal system by absorbing and retaining torrential rains. The U.S. city of Portland, Oregon as well as Toronto, Canada has already begun exploring the possibility of soaking up such benefits. Tokyo City’s fathers have not been able to ignore the myriad benefits of this simple science either.

Following similar legislation in Germany and Switzerland, Tokyo in 2001 passed an ordinance mandating that all new private-sector buildings with more than 1,000-square foot of rooftop dedicate at least 20 percent of it to gardens. In doing so, city leaders aim to increase metropolitan area green space from 29 percent to 32 percent — by nearly 3,000 new acres.

Last December, Minato Ward one-upped Tokyo’s green-roof ordinance. In an ambitious effort to see its green space grow by 20 percent, the municipal government waters private enterprise with public funds to plant greenery on wall and fence tops, balconies and roofs. The new law subsidizes rooftop greening by up to half the cost or 20,000 yen per square meter which ever is less, with a 300,000-yen maximum for both new and existing buildings. Coming on the heels of a 2001 study that showed the ward’s 18.46 percent of green space was continuing to wither, the ordinance applies both to all new structures as well as already standing buildings with lots less than 250-square-meters. The emerald jewel of Minato and Tokyo’s crowning achievements to date is the palatial Roppongi Hills mixed-use development — the largest redevelopment project ever realized in Japan.

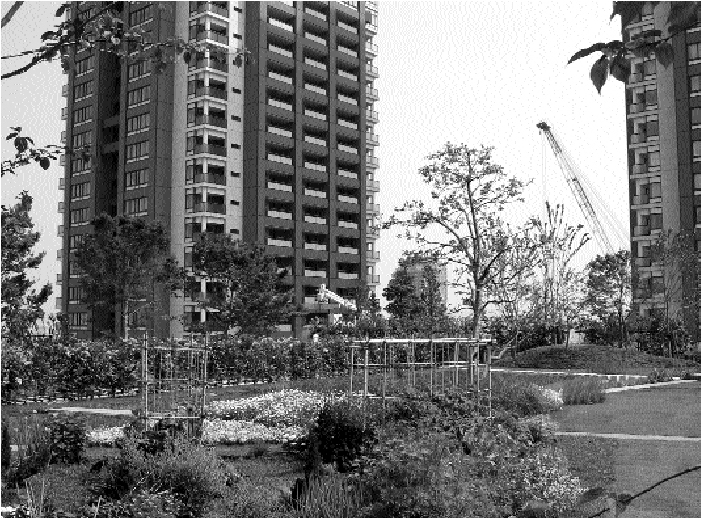

Mori Building Co.’s urban ambition to create „vertical cities with verdant gardens brought in well-known English-born landscape designer Dan Pearson to blend British principles with indigenous sensibilities and flora for an East-meets-West showcase of sky-garden splendor. Roppongi Hills touts 13 roof gardens on residential buildings and another five topping prime commercial space such as the Keyakizaka Complex and the home of Asahi TV. With half of the property being open space, and 26 percent of that sporting green, it could indicate the wave of the things to come.

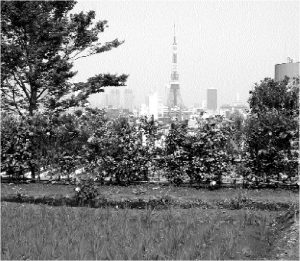

“As the philosophy of Mori Building Company has been to create a vertical garden city, rooftop gardens are one of the ways for us to recover the lost greenery in urban centers,” says Mori representative Masa Yamamoto. “For customers and visitors, these gardens give them a relaxing and refreshing atmosphere.” The up-scale property has much of its patches of paradise — cherry trees, sparkling waterfalls and killifish-filled lakes — almost exclusively reserved for the privileged few. But guided tours offer glimpse of the high-end of high-rise Eden: lush Indian lilacs, fragrant orange trees and, atop its seven-floor Keyakizaka Complex, 1300-square-meter organic koshihikari rice paddies with a birds-eye view of Tokyo Tower. The urban oasis boasts classic persimmon trees, a sizable herb and vegetable garden and a lily pond, which is home to an array of fowl and dragonflies. Ecologically, in so far showing the fiscal feasibility of tending a garden, such large-scale projects are sowing a commercial precedent. But it was the public sector that first seeded the city with the garden of green rooves now taking root.

Public buildings have also been getting the leafy toupees. Ward offices in Shibuya and Sumida, and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transportation have green growing out of their roofs. The land ministry has even posited the idea of a fixed-asset-tax break for roof-garden equipment. The ward-office gardens are for more than just public strolling. Officials use them as models with educational displays, events and tours to promote the idea. While Sumida has a long-term goal to see half of its rooftops sporting green, Shibuya aims to up green space from 21 percent to 23 percent. The ward’s 550-square-foot rooftop park has attracted about 10,000 visitors since it opened in 2002, officials say.

Public buildings have also been getting the leafy toupees. Ward offices in Shibuya and Sumida, and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transportation have green growing out of their roofs. The land ministry has even posited the idea of a fixed-asset-tax break for roof-garden equipment. The ward-office gardens are for more than just public strolling. Officials use them as models with educational displays, events and tours to promote the idea. While Sumida has a long-term goal to see half of its rooftops sporting green, Shibuya aims to up green space from 21 percent to 23 percent. The ward’s 550-square-foot rooftop park has attracted about 10,000 visitors since it opened in 2002, officials say.

The modest four-story-high garden in the sky offers manicured ground cover, a deck and gazebo-covered park benches and a sampling of descriptively labeled gardening techniques and plants. It host projects installed by different companies, with displays ranging from green cone conifers and a tiny fish-laden pond, to raised vegetable gardens producing eggplant, tomatoes and herbs.

“There are three reasons why roof gardens are beneficial,” says an official at Shibuya Ward office. “It adds more green space to Shibuya, it helps resolve the heat-island problem and it provides insulation from the heat and the cold.”

Indeed, various studies have shown that a soil and vegetation covered roof — with insulation values roughly half that of man-made fiber — also helps keep upward flowing heat in during winter months. It’s even said that the gardens can muffle the deafening blare of urban noise. Other than the succulent scents of springtime blossoms, definitive olfactory benefits from foliage barriers have yet to be determined, but some public sewerage facilities have used them to come out smelling like a rose.

Ochiai Wastewater Treatment Plant in Shinjuku last year brought recycling into the picture with bench and deck materials composed of leftover construction wood, light-weight soil comprised of incinerated sewage sludge and reclaimed treated water to irrigate its 560-square-meter rooftop plot. The idea spilled over from Kasai, Edogawa Ward, which incorporated a similar full-fledged 361,744-square-meter park, complete with office, outdoor lighting and two baseball fields, atop the wastewater treatment plant that that city built in 1982. Such sturdy low-squat structures, which might otherwise be paved over for car parking, are ideal for wearing the kind of green space that architects can only dream of outfitting their high-rise counterparts with.

The main challenge to rooftop gardens is weight. It’s one reason why incorporating them in the design of new buildings is much more cost effective than adding them to existing structures. “The ratio between rooftop gardens we build on new versus existing buildings is about 8:2,” says Kajima Co.’s Okada. “New buildings have more flexibility in design, cost and construction. This may explain why most rooftop gardens are built on new buildings.” Costs vary widely, he says, but generally range around 30,000 yen per square meter for large-scale commercial ventures. But lighter soil mixtures with additives such as of highland peat that Shibuya officials have experimented with, incinerated sludge used by Ochiai water treatment plant in Shinjuku, and cedar used by Kajima are being combined with innovations including light-weight plastic foam decks to get around the problem. And with groundbreaking ordinances such as Minato Wards subsidy program, which includes already constructed buildings as well as new developments, more gardens may soon spread to existing rooftops.

It’s no stretch that in an urban setting where tiny slivers of personal green — in window seals, street-side flower boxes and even Styrofoam crates — abound, roof gardens could catch on. Some are already betting on it. General contractors are pushing the light-weight stuff of which sky gardens are made, and it’s not unusual to eye the essential ingredients in home-furnishing and do-it-yourself shops for lay gardeners to plant a little patch of nature over their own heads.

“People really like it,” the Shibuya official says of public reaction to the ward’s model roof garden. “Many people say they wish they could start a rooftop garden at home.”

Story by Oscar Johnson

From J SELECT Magazine, June 2004

Recent Comments