The wandering performers, charcoal-makers and peddlers that once traversed the eastern coast of the Izu Peninsula have long since vanished, but much else has remained remarkably unchanged. Along a seaboard corridor more suggestive of a rustic country route than a vector for north-south passenger traffic, cedars and other trees line slopes and gorges leading to hot spring resorts, attractive hiking trails, waterfalls, and swimming holes.

Trains pass by landscapes of lumpy green hills, random conical shapes resembling giant topiary. A southern climate is evident here in the small orange groves, trellises of wisteria along the riverbanks, and the odd outcropping of cycads and cactus. A striking feature of this region is its namako-kabe designs. This crisscross plasterwork in gray and white used to decorate walls characterizes many of the homes, shop fronts, and storehouses of the peninsula. The appealing harlequin patterns, popularized during the Edo period, also fortify buildings against the typhoons that lash the peninsula in late summer and early autumn.

Although a minor early work, Yasunari Kawabata’s semi-autobiographical story, ‘Izu no Odoriko’ (‘The Izu Dancer’), supports a lucrative micro-tourism industry in these parts. The commercialization of the Nobel Prize winning writer’s tale is evident in the pointedly named Izu Odoriko express train that brings travelers to Shimoda and the popular Odoriko hiking courses. This should not put you off venturing into Kawabata country, though. Even during national holidays and other peak travel times, there always seems to be enough space to go around.

Atami is often – and rightly – described as the gateway to the Izu Peninsula. At just 50 minutes by bullet train from Tokyo Station, it is highly accessible and much visited, despite its reputation as a faded hot spring resort, a decidedly uncool destination for today’s uber-tourist. Visitors may snigger at its old sobriquet, the “Capri of Japan,” but strip away the raw clutter, tetrapods, cement storm breaks, and the part of town that caters to sex tourism, and the outline of the bay, the mountains and slopes, the sinuous shoreline that forms a stunning green amphitheater, are still there. Its merits may not always be immediately visible, but yet Atami is still frequented by tourists in large numbers, including the young. This is at least partially due to its coastal location, the foretaste of better beaches to the south, offering more expanses of sun, surf, and sand.

Atami is often – and rightly – described as the gateway to the Izu Peninsula. At just 50 minutes by bullet train from Tokyo Station, it is highly accessible and much visited, despite its reputation as a faded hot spring resort, a decidedly uncool destination for today’s uber-tourist. Visitors may snigger at its old sobriquet, the “Capri of Japan,” but strip away the raw clutter, tetrapods, cement storm breaks, and the part of town that caters to sex tourism, and the outline of the bay, the mountains and slopes, the sinuous shoreline that forms a stunning green amphitheater, are still there. Its merits may not always be immediately visible, but yet Atami is still frequented by tourists in large numbers, including the young. This is at least partially due to its coastal location, the foretaste of better beaches to the south, offering more expanses of sun, surf, and sand.

As a young woman, my mother-in-law stayed for a couple of nights at a rustic inn somewhere in Atami. She thinks it was 1962, when you could walk straight down to the beach without all the impedimenta of footbridges, traffic lanes, cement ramps and split-level promenades. When she visited last year, she lamented the developments, until that is, she recalled how much nicer, more comfortable, and well serviced her accommodation was this time around. This, perhaps, is how we forget the past, by superimposing the new and putatively superior on our memories.

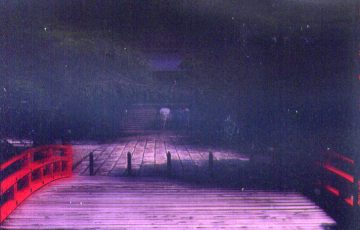

The mountains bring unpredictable rain to this coast, black thunderheads forming out of perfectly blue skies. And when the storms hit, you won’t find a bus shelter, waiting room, or pergola in sight. Atami is designed to conspire with the elements to drive its cash-fluid visitors into the paying refuges of cafes, hotel lobbies, souvenir shops, and museums.

The charming railway journey down from Atami to Shimoda is reason enough in itself to visit this slightly warmer clime, rich in coastal diversity and plant life. Shimoda has its own beach, a very decent stretch of sand called Shirahama, but there are even better prospects to the south. Just four kilometers south of Shimoda, Kisami Ohama is an attractively sandy bay popular with surfers. Come here in late spring and you will find an almost deserted beach. In summer the tourists will be as thick as sand flies.

The charming railway journey down from Atami to Shimoda is reason enough in itself to visit this slightly warmer clime, rich in coastal diversity and plant life. Shimoda has its own beach, a very decent stretch of sand called Shirahama, but there are even better prospects to the south. Just four kilometers south of Shimoda, Kisami Ohama is an attractively sandy bay popular with surfers. Come here in late spring and you will find an almost deserted beach. In summer the tourists will be as thick as sand flies.

Further down the coast, the Tokai Bus stops at Kyukamura, a village right on the bay with a view of the broad beach of Yumigahama, one of the finest expanses of sand in the entire peninsula. You can actually see the beach from the bus stop. In the usually sunny month of May the beach will still be uncrowded. That also applies to most of June, the rainy season, but by the weekends of July and August, finding a patch of sand here will be as difficult as securing a picnic spot in Ueno Park during the cherry blossom season. Cops of tall palms and casuarinas line the bay, and there is a pleasant fish restaurant on the approach road to the beach. Here you can sit at outside tables and watch the comings and goings.

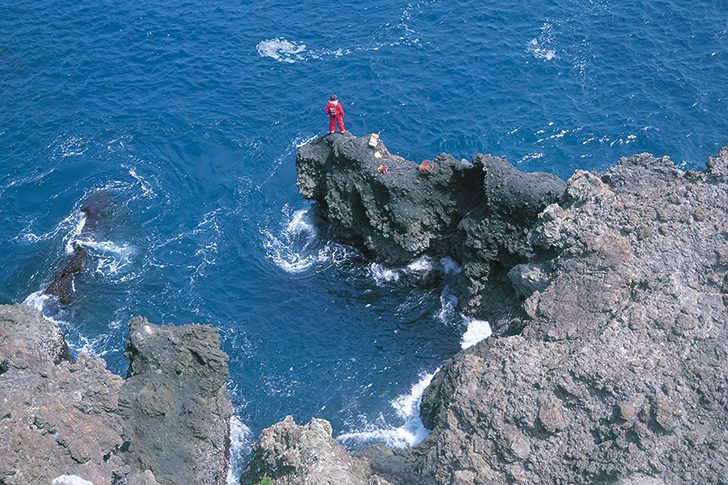

Continuing south to the very extremity of the peninsula, the bus passes through a countryside of rich, almost sub-tropical vegetation, to the headland at Iro-zaki, where the main attraction is less beach than the dramatically indented coastline. The walk from the bus stop passes through what seems to be an exhibit to failed business ventures: abandoned cafes, horticultural hangars, restaurants, a game center, all in the mid stages of ruination, walls and entrances encroached on by weeds, palms and, cycads going to seed. This may be the remains of what old guide books refer to as Iro-zaki Jungle Park, a complex that once boasted over 3000 varieties of tropical plants, many of them now bursting out of confinement and returning to nature. If you happen to be on the cape in January, the whole area is covered in yellow daffodils.

Continuing south to the very extremity of the peninsula, the bus passes through a countryside of rich, almost sub-tropical vegetation, to the headland at Iro-zaki, where the main attraction is less beach than the dramatically indented coastline. The walk from the bus stop passes through what seems to be an exhibit to failed business ventures: abandoned cafes, horticultural hangars, restaurants, a game center, all in the mid stages of ruination, walls and entrances encroached on by weeds, palms and, cycads going to seed. This may be the remains of what old guide books refer to as Iro-zaki Jungle Park, a complex that once boasted over 3000 varieties of tropical plants, many of them now bursting out of confinement and returning to nature. If you happen to be on the cape in January, the whole area is covered in yellow daffodils.

Press on and you will come to a lighthouse and a narrow path that leads down to a tiny shrine, perched on a promontory overlooking jagged cliffs and clusters of rocky islets. The views here are surely some of the most magnificent to be had on the peninsula. Once you have had a lungful of salt air, retrace your steps and then follow a path to the right, which will take you past a beautifully calm inlet, and then down to a fishing village with a modest degree of tourism, in the form of souvenir shops and car parks. The bus stop, where you can return to Shimoda for the train transfer, is just up the road from here, but you may wish to linger. The sunsets off the cliffs are legendary.

TRAVEL INFO

Trains leave for Atami and Shimoda regularly from Tokyo Station. These include both local trains and the shinkansen. Buses leave Shimoda station every 30 minutes for the route down to Iro-zaki. One of the best ways to see this southern coast is to use the bus one-way, the boat back to Shimoda the other. If you really want to splurge, Horai (0557/80-5151) is Atami’s most elegant inn, replete with separate cottages, and a wonderful outdoor spring overlooking the bay. Ernest House (0558/22-5880/ www.errnest-house.com) has brightly lit rooms a minute’s walk from the beach in the village of Kisami.

Story and Photographs by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, August 2010

Recent Comments