Buffeted by the whims of larger, more powerful nations and isolated from the international community, Laos, at least until a few years ago, remained more rumor than reality, its capital, Vientiane, an anomaly on the world map. With the completion in 1994 of the Australian-funded Mitprahab, or Friendship Bridge, connecting Vientiane with neighboring Thailand, and the increasing economic interest in the development of the Lower Mekong Basin, Vientiane’s days of charming obscurity could well be numbered.

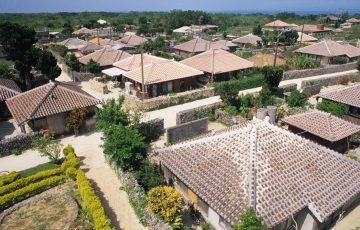

Three decades of colonial and civil wars have left Vientiane remarkably intact. Most of the damage to its buildings has come more from neglect, a lack of funds and the seditious tropical climate, than from warfare or civil strife. Vientiane remains an urban time capsule, a minor but intriguing mosaic of French, Chinese and Lao influences. Pavements are broad, bedevilled with missing or lopsided flagstones, and tend to sprout with banana fronds, weeds and sundry fauna. This backwater of old Indochina, where few buildings rise to over two storeys, may appear to the casual observer to be little more than a minor Mekong port town, but there are clear signs of a reawakening.

Buddhism, the Hinayana school practiced in Laos and neighboring Cambodia, has regained much of its former official approval and is again in favor with the authorities. Until only a few years ago, monks were persecuted, but now the temples are again centers of activity and learning. Brightly painted billboards proclaiming the achievements of the World Proletariat Revolution can still be seen along the streets of Vientiane and elsewhere, but most Lao would agree that these sentiments are little more than token anachronisms.

The French, who were largely responsible for reclaiming Vientiane from the mercies of the jungle, colonized the country from 1893 to 1954. Paradoxically, Vientiane continues to be something of a French creation, the marks of colonization drawn in broad strokes across its dusty boulevards and street cafes. The Lao may have risen up against their colonial masters but a pervasive gastronomic legacy endures in Vientiane. The faces of the maitre’d and waitresses at Santisouk in the Quartier Chao Anou may be Lao, but the surroundings are little different from those of a restaurant in the suburbs of Lyon or Nantes. Some of Vientiane’s restaurants are French-run in fact, like the Vandome near Wat Impeng. Another, the Restaurant Arawan near Wat Simoun, is run by a family who seem to genuinely enjoy plying their guests with good red wine and rustic French cheeses.

Dilapidated colonial villas with shuttered windows and airy balconies stand in the middle of small banana groves, many under the restoration orders of Vientiane’s nouveau riche traders, shopkeepers, brokers and compradors for the increasing number of foreign businessmen seeking investment opportunities in Laos. The outward signs of this release of entrepreneurial energy are evident on almost every street corner. Well-stocked shops, shelves lined with Chivas, Vat 69 and pyramids of tinned pate and artichokes, are a small foretaste of the cornucopic morning market. The name is something of a misnomer as the market remains open, fomenting with activity, throughout the day – a sprawling emporium of shop lots stuffed with every conceivable type of consumer good, from Japanese electronics and French perfumes to the exquisite silk handicrafts of Laos’s lowland textile communities and hill tribe weavers.

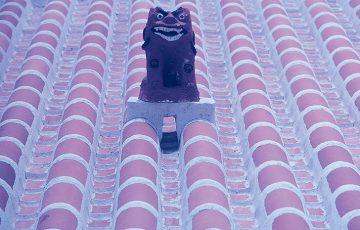

A few reminders of Vientiane’s importance as a religious center still exist and are easily found in this diminutive capital. Wat Simoung, on the edge of town, contains the city’s foundation stone – lak muang – dating from 1563. Thought to be an old Khmer boundary stone, the pillar and its attendant Buddha are supposed to have magical powers and are much consulted by devotees of the temple. Wat Si Saket, near the Presidential Palace, was the only temple in Vientiane to have survived the torching of the city intact and is, therefore, the ‘newest’ of Vientiane’s old temples. Standing in its own gardens, Wat Si Saket is a functioning temple with monks’ quarters attached, and also a museum. The temple, whose surrounding cloisters house hundreds of small Buddha statues in terracotta, wood and bronze, was consecrated in 1824, with a sumptuous procession in which “torches lit up bouquets of flowers, whose perfume permeated the air… and music resounded to the skies, reaching the four corners of the universe.”

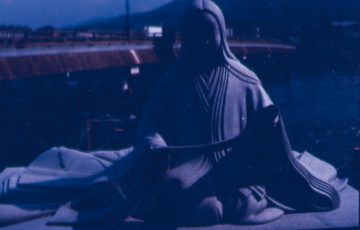

Laotian religious art finds another home at Wat Phra Keo, another of Vientiane’s temple-museums. The exhibits along the raised galleries, peristyle and the interior of the sim (ordination hall) strongly evoke Vientiane’s age as an eminent religious center. Another masterpiece of Laotian art stands at the end of Thanon Lane Xang, on a slight elevation above the city. Wat That Luang, described by art historian Bernard Groslier as “one of the great achievements of Buddhist architecture,” dates back in its original form to 1556. Supremely important to the Lao, That Luang is more than just the emblem of Vientiane – it is the national shrine. Later restorations and additions, such as the stockade-like cloisters surrounding the compound, distract the attention a little from the temple’s centerpiece, a hemispherical stupa, beautifully contoured, flowing upwards like a lotus flower from its bed of leaves.

As an exercise in transplanted Gallic architecture, Vientiane is less successful. The Laotian capital never achieved the elegance of Hanoi or the importance of Saigon, France’s “Pearl of the Orient,” as the French never thought of Laos as being more than a minor member of the Union of Indochina, the back garden of her empire in the East.

Perhaps so, but the source of Vientiane’s insouciant and very tangible charms issue from that very marginality which has kept it a provincial time-capsule. A less abrasively urban capital could hardly be imagined, and Vientiane remains a city that accords its visitors a gentle courtesy that seems to belong to a different age, offering the senses smidgens of a faded European grace that blends easily with Oriental exotic. Here is a city that lives in the past but which, like a kindly, overlooked elderly dowager, is now being recalled from its genteel poverty, and asked to rejoin the world.

“A less abrasively urban capital could hardly be imagined, and Vientiane remains a city that accords its visitors a gentle courtesy that seems to belong to a different age, offering the senses smidgens of a faded European grace that blends easily with Oriental exotic.”

TRAVEL INFORMATION

June to October is the rainy season, though there can be clear days. November to February are the temperate months, and consequently the high season for visitors. March to May is the hot, dry season with cloudless, blue skies and temperatures that can soar to 44 degrees Celsius. There are two daily Thai Air flights to Vientiane from Bangkok. There are also flights from Singapore and other Southeast Asian cities. Visas are not required in advance and can be obtained at the airport or at the river crossing. They cost US$30, and require the presentation of three passport-sized photos. The Lane Xang Hotel is one of the older top-class hotels. The popular La Parasol Blanc is an excellent accommodation with a pool and a highly recommended restaurant. Another excellent option is the Villa Manoly, near the river (tel: 856-21-218907, e-mail: manoly20@hotmail.com). Travelers need to be aware of the usual precautions for a tropical country. Vientiane is not a malaria zone, but if you are thinking of doing side trips from the capital, check out the available courses. The Rough Guide to Laos and the new edition of the Lonely Planet are both excellent books to carry. Consult Culture Shock! Laos for background on culture and behavior, and Dervla Murphy’s first rate travelogue, One Foot in Laos, for pleasure.

Story and photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, August 2004

small-150x150.jpg)

Recent Comments