Dr Mamoru Mohri, director of the National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation, captured the imagination of an entire generation with his exploits in space in the early 1990s. Rather than rest on his laurels, however, the man who has spent 19 days looking down on the earth from on high is working tirelessly to make science and technology accessible to all and, in doing so, help sustain life on this fragile planet. Jonathan Day reports.

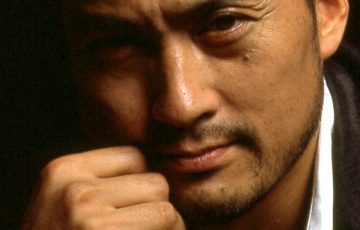

At first glance, Dr Mamoru Mohri hardly fits the stereotype of your average scientist. Looking more comfortable in a striking three-piece suit than a starch-white lab coat, his debonair appearance actually belies the string of academic letters that follow his name.

Mohri graduated from Hokkaido University with a Masters of Science degree in chemistry before heading to Flinders University in South Australia to complete his doctorate. He returned to his old university campus in northern Japan in 1975, procuring employment in the Department of Nuclear Engineering and rising up through the ranks to the position of associate professor.

In 1980, Mohri was selected as one of the first exchange scientists under the US-Japan Nuclear Fusion Collaboration Program on the back of his scientific accomplishments and growing reputation. Five years later, the National Space Development Agency of Japan (NASDA) chose him to be a payload specialist for the First Material Processing Test Project (Spacelab-J) and in 1992 a cooperative mission between Japan and the US was launched to conduct experiments in materials processing and life sciences. During this eight-day mission, he performed 43 experiments with NASA astronauts aboard the space shuttle Endeavor. The televised tests were beamed into homes, classrooms and laboratories all over the world, and “Mohri-san” became a household name here in Japan.

Eight years later and he would once again board the space shuttle Endeavor, this time as a mission specialist responsible for mapping 47 million miles of the earth’s surface in just 11 days – a formidable feat. This time, however, the mission would affect him deeply and personally, both during the 268 hours he spent in orbit and upon his return to terra firma.

“Our mission was to collect three-dimensional data on the world’s topology and during the mission I personally saw the earth from space almost 200 times,” recalls Mohri as he relaxes on a leather chair in his moderately lavish office, located deep in the belly of the National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation in Odaiba. “The earth is so big and, at the same time, so small,” he states profoundly, leading me to believe there’s a lot more to this man than meets the eye.

“I knew there were 6.3 billion people living on that globe, and not only people but other species too,” he says. “I could see all that from a distance. I saw how such a thin layer of atmosphere could sustain all kinds of life forms. At night I saw many, many brilliant lights all connected like a network and once again I realized how big indeed the earth is, yet its natural resources are so limited. Humans have started to change the environment very rapidly and this sudden change, in such a long history, came from the development of science and technology – controlling energy and using high technology.”

“Then I returned to earth,” he continues without pausing. “Everyday I heard news about war, regional problems and natural disasters like earthquakes and once again I remembered how fragile the earth is. However people should realize now that science and technology can help sustain it.”

Such awareness has compelled Mohri to make a direct contribution to the improvement and advancement of society, particularly in regard to its sustainability. Thus, when he was asked to become director of the National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation four years ago, he knew he could put his experiences to good use, educating the masses on the important role science plays in society.

The museum, more commonly referred to as MeSci (a shortened acronym comprised of the words “Me” and “Science”), holds its patrons as the nucleus of the entire scientific cell. As visitors see with their own eyes cutting-edge science and technology at the museum, the hope is that they ask themselves, “What does science and scientific technology mean to me?”

The museum building is an architectural marvel, an elliptical fusion of glass and metal. In fact, one face of the building is comprised entirely of glass, symbolizing that the space is open to all and allowing information to flow freely in and out of the museum. On entering the museum one can’t help but notice the 6.5-meter diameter globe floating in open space between the first and the sixth floors. One million light emitting diodes on the sphere display data received from orbiting satellites, with a lag-time of just one hour. The music that accompanies this exhibit is produced by none other than Ryuichi Sakamoto and adds a certain aura to the proceedings. This globe, known as the Geo-Cosmos, was created at the behest of Mohri to “share with others the bright image of the earth as seen from space.”

Sharing and improving the public’s affinity towards science is central to Mohri’s personal creed and the museum’s very own founding principles, as he himself explains.

“‘Emerging’ and ‘innovation’ are key words in the running of this museum and there is no such museum in the world quite like ours,” he says. “We are dealing mainly with Japanese emerging sciences and innovation field exhibits, however our concept is a little different from conventional museums or science centers. We want to promote the scientists and engineers who are personally involved in very advanced contemporary science and innovation, through interpreters and volunteers, not only through the exhibits.”

The museum employs more than 60 interpreters, all of who hold at least a Masters-level qualification in a diverse range of scientific and engineering fields. The museum also utilizes an additional 800 volunteers, many of whom are retired scientists or engineers looking to make a valuable contribution to society later in life, or college students wanting to supplement their studies and meet a valuable network of budding scientists and engineers. The interpreters and volunteers are integral to the museum’s concept of making cutting edge science accessible to all. The museum’s exhibits, by nature, are not the easiest to understand by those not possessing a scientific background and, although many of the exhibits are hands-on and fully interactive, the interpreters and volunteers provide essential information to the patrons at a level they can understand.

“The volunteers are definitely a part of each exhibit,” he says. “And quite a number of our interpreters can speak English. Laypeople, although they can ‘see’ emerging technology, they can’t always understand the background. Visible things are OK, but non-visible innovation like human genome or stem-cell research are very advanced technologies that can’t be seen so easily. These may influence you and your life greatly in the future – in the very near future. We like to expose such new emerging technologies to the people when they come here, through our exhibits and our staff.”

Story by Jonathan Day

From J SELECT Magazine April 2005

Recent Comments