If you had time to explore every stop on the Kintetsu line, from Kyoto down to, say, Ago Bay in Mie prefecture, you would discover a descending history, from grand stone fortifications and temples to the watery shores of the Ise Peninsula, its craggy fishermen and abalone divers.

If you had time to explore every stop on the Kintetsu line, from Kyoto down to, say, Ago Bay in Mie prefecture, you would discover a descending history, from grand stone fortifications and temples to the watery shores of the Ise Peninsula, its craggy fishermen and abalone divers.

Matsusaka in the center of Mie, is known to most people in Japan and to a handful of food fanciers abroad, for its marbled, highly sought after beef, the kind served in expensive restaurants. Few visitors, however, bother to go beyond the dining table. The city and its enterprising merchants have always known how to promote trade and local produce, but less so tourism, which, despite the town’s blue-chip cultural and historical credentials, seems almost like an afterthought.

Like almost everywhere in Japan, violence-free streets allow complete exploration, that wonderful freedom that comes from a sense of being safe. And there is, surprisingly, much to seek out there. Matsusaka’s heyday was unquestionably the Edo period, when the town flourished as a producer of high quality indigo-dyed cotton. Matsusaka kimonos, many with a distinctive stripped pattern, were considered de rigeur in Edo (present-day Tokyo) and much sought after. Examples of original designs and indigo cotton looms, can be seen at the town’s Museum of History and Folklore. Fortunes were made from the textiles, and some, like the one accrued by the founder of the Mitsui Group, have lasted.

Initially, like so many Japanese railway towns, Matsusaka appears to be a scruffy, uncoordinated place, something like an early 20th century mining town. It’s wise to set first impressions aside in Japan, though in this case you will find that Matsusaka has its fair share of quite distinguished houses, temples and historical ruins.

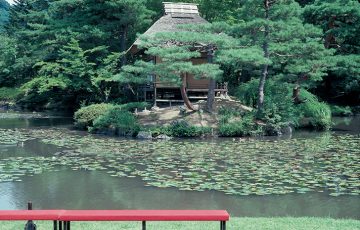

The Chinese characters for the town’s name signify ‘pine’ (matsu) and ‘slope’ (zaka), the etymology no doubt stemming from the fact that when the castle was constructed in 1588, the site chosen was a hillside forest. The older parts of the city in fact, are fossilized around the castle ruins. There is something admirable about the fact that the city has not decided to build yet another cement replica of the original castle, like so many other towns in Japan. The ruins speak for themselves, and eloquently. Now called Matsusaka Park, the fortifications are raised high, affording commanding views of the city. Cherry trees bloom in the spring, wistaria in summer, softening the colossal stone fragments that make up the castle’s still intact foundation walls. The fortress was constructed under the orders of Ujisato Gamo, a man of some culture apparently, who later converted to Christianity.

On the edge of the ruined grounds, a grand, two-part villa with a gated entrance turns out to be the Suzunoya Kyutakku and Motoori Norinaga Kinenkan, the former home and museum of a well-known 18th century scholar, poet and historian, who spearheaded a movement to restore the status of Japanese literature and Japan’s nativist religion, Shinto. Norinaga’s proto-nationalist ideas were based on the total rejection of all foreign culture, particular Chinese. The restored house and study, the Suzunoya (House of Bells), is named after Norinaga’s epistolary name

Gojoban Yashiki, just outside the castle boundaries, is a lane of old homes once belonging to the samurai assigned to guard the castle grounds. It was here, among the nineteen, still perfectly intact wooden houses that the samurai lived with their extended families. Six are still inhabited by direct descendants of those warriors. The well kept terraced homes are modest, divided by neatly trimmed podocarps, as prim and proper as any English suburban garden privy hedges.

Gojoban Yashiki, just outside the castle boundaries, is a lane of old homes once belonging to the samurai assigned to guard the castle grounds. It was here, among the nineteen, still perfectly intact wooden houses that the samurai lived with their extended families. Six are still inhabited by direct descendants of those warriors. The well kept terraced homes are modest, divided by neatly trimmed podocarps, as prim and proper as any English suburban garden privy hedges.

Northeast of the castle, Uo-machi is a district of well-preserved merchant homes. The area includes a rather grand gate, taken from the former estate of the powerful Mitsui merchant family. The atmosphere of the Edo period is strongly sensed at the Memorial Museum of Matsusaka Merchants, a two-storey home with all of its original features, including kitchel utensils, money-boxes and tansu chests, intact, two plaster-walled storehouses and a set of tiny, meticulously cared for gardens, intact.

A very different kind of museum stands on the other side of town from the castle domain. The Ozu Yasujiro Seishunkan Museum is dedicated to the man many people consider to be Japan’s premier film director, though foreigners will be more familiar with the works of movie auteurs like Akira Kurosawa and Nagisa Oshima. Ozu (1903-1963) was born in Fukagawa ward in Tokyo, but moved with his family to Matsusaka, his father’s home, when he was ten. He lived there until moving back to Tokyo to join the Shochiku Film Company as a cameraman in 1923. Ozu’s themes, nicely displayed in stills and commentary at the museum, were the struggles of ordinary people in post-war Japan. In films like Tokyo Story and I Was Born, But… Ozu also examined the collapse of the Japanese family. Donald Richie has called an earlier Ozu film, Story of Floating Weeds, ìthe first of those eight-reel universes in which everything takes on a consistency greater than life: in short, a work of art.

Despite all the history and culture the town enjoys, the beef association cannot be ignored. The cows raised there are only female. Fed on tofu lees, high-fiber fodder like ground wheat, soybean by-products and corn, beer is served as a kind of aperitif to stimulate interest in the food when the animals lose their appetite. The resulting wagyu (Japanese beef) is considered by many epicures to be superior even to the famous Kobe variant. The high fat-to-meat ratio though, makes it highly unhealthy. As few people outside the circle of well-heeled gourmands and the occasional Japanese Prime Minister can afford to eat it regularly, that’s usually no problem.

Despite all the history and culture the town enjoys, the beef association cannot be ignored. The cows raised there are only female. Fed on tofu lees, high-fiber fodder like ground wheat, soybean by-products and corn, beer is served as a kind of aperitif to stimulate interest in the food when the animals lose their appetite. The resulting wagyu (Japanese beef) is considered by many epicures to be superior even to the famous Kobe variant. The high fat-to-meat ratio though, makes it highly unhealthy. As few people outside the circle of well-heeled gourmands and the occasional Japanese Prime Minister can afford to eat it regularly, that’s usually no problem.

TRAVEL INFORMATION

There are four stations there, but the main one is Matsusaka Station, where all JR and Kintetsu trains stop. There is also a bus terminus near the JR exit. There are several handy business hotels close to the station. Rates at the comfortable Matsusaka Green Hotel (598-26-6611) start at ¥6,300. Several restaurants near the station serve Matsusaka steak courses. Steak House Mimatsu, designed like an old Japanese farmhouse, is one of the most famous.

Expect to pay between ¥9,000-18,000 for dinner. The Motoori Norinaga Memorial Museum (admission ¥300) is open Tues-Sun, 10am-5pm. There are many stores selling indigo cotton fabrics. One of the best is the Matsusaka Momen Tezukuri Center.

Story and photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, January 2009

Recent Comments