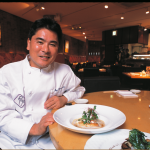

Designer Limi Yamamoto unveils stunning new autumn/winter collection in bid to shake outdated “loose silhouette” tag, writes Elliott Samuels. Portraits by David Stetson.

Japanese designers have been at the forefront of international fashion ever since Kenzo Takada made his successful debut in Paris in 1970. Using kimono textiles in an unfamiliar way, his casual creations came to represent the beginnings of pret-a-porter clothing that was stylish as well as suited for everyday life. Inspired by the success of Takada’s Paris debut, other Japanese designers were quick to follow suit. Issey Miyake held his first show in New York in 1971 and in Paris in 1973, unveiling a line of clothing that was based around the concept of “A Piece of Cloth.” Miyake was particularly interested in highlighting the ma (space) that was created when the human body was covered with a single piece of cloth. As each person’s figure was different, he believed the ma was unique in each instance, creating an individual form.

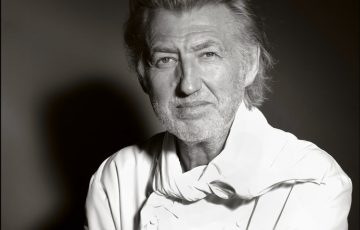

The 1980s saw the arrival of Comme des Garcons’ Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto, two Japanese designers who worked with monochromatic, torn and non-decorative material that reintroduced an element of shabbiness into the world of fashion. It was a deliberate expression of absence rather than existence. Yamamoto in particular synthesized refined European tailoring and Japanese sensibility, implying in his work that international clothing can come from a culture other than that of the West.

The emergence of these designers in the 1970s and ‘80s put Japan squarely on the global fashion map, beginning an international fascination with all things Japanese that continues to this day.

However as these pioneers’ careers have flourished, those close to the local fashion industry have become aware that a new generation of Japanese designers needs to be groomed to follow in their footsteps. Fears that success on the catwalk will end with the retirement of the likes of Miyake and Co have been largely allayed with the emergence in recent years of young designers such as Issey Miyake protege Naoki Takizawa and Chisato Tsumori.

But as Takada, Miyake and Yamamoto showed on their respective debuts overseas, for a Japanese designer to be successful internationally they need more than just a name and a reputation of raw talent behind them – they need an established brand. And no-one is more acutely aware of this than Yamamoto’s only daughter, Limi, an up-and-coming designer in her own right who is working tirelessly to establish her own line of clothing in Japan before targeting international markets.

“Being Yohji Yamamoto’s daughter has its pluses and minuses,” says Limi Yamamoto at her studio in the quiet back streets of Roppongi. “On the one hand, I get more attention. On the other, people assume I am a good designer because I am his daughter and are quick to judge me. I can sometimes feel a little uncomfortable.”

Graduating from Bunka Fashion School in Tokyo, Limi initially cut her teeth in the fashion industry by working as a patterner at Y’s. Not content with merely drawing patterns, she got into designing and launched her own label in March 2000 under the name “Y’s bis LIMI,” which she renamed “LIMI feu” two years later.

“I love clothes,” Limi says,” and with my own label I can make the clothes that I want to make. Unfortunately, the downside with running my own label is that I must stick to my budget. I put a cap on spending at the beginning of each season, which can sometimes limit what I am able to make.”

Limi’s designs have been described by critics as “loose silhouette,” a label she does not necessarily wish to stick. “I like loose fashion and maybe my previous designs have reflected this,” she says. “However, in my latest collection [A/W 2005-06] I went out of my way to avoid this style, utilizing top-of-the-line fabrics and beautiful patterns to come up with something that looks a lot more tailored. It’s my statement against the grunge movement that young people in Japan seem to prefer these days. I think such a style looks a little too sloppy.”

Limi, 35, says her latest line of clothing should not really be pigeon-holed into any particular category because it does not have a dominant theme.

“I wanted this collection to be conceptually free,” she says. “If I thread a common theme through the clothes, I find there is less scope for imagination. For example, if I describe my clothes as being ‘army style’ people start think of double pockets and shoulder boards etc, even though I don’t mean that.”

Inspiration for her designs comes from things Limi encounters on a day-to-day basis when walking around Tokyo. She is not particularly interested in tapping into contemporary pop culture. “I never get inspired by music or films,” she says. “I don’t really think my private life has anything to do with my design style. I get more inspiration from what I see people wearing on the streets of Harajuku and Daikanyama, and by talking with other designers.”

Being a self-confessed perfectionist, Limi says she typically puts in long hours in the weeks leading up to the launch of a collection. Even so, she is usually more worried about the well-being of her staff during this time than how the collection will be seen by critics. “Buyers are primarily concerned with ‘LIMI feu’, so I don’t really need to be worried about myself,” she says. “However I do worry about the health and mental state of the people I work with. They can get rundown in the lead up to a collection. I have staff who have come to Tokyo all the way from Kyushu or Hokkaido. They live by themselves and have a tough life. I know their personal situation shouldn’t concern me, and yet it does. Of course I expect my staff to look after me when I am not feeling 100 percent!”

Few of the leading names in fashion make the effort to showcase their designs in the biannual Tokyo Collection, choosing instead to focus on the more publicized events held in Paris, London or New York. When asked how the Tokyo Collection can be improved in light of its poor reputation on the international circuit, Limi says local designers need to work together in a more centralized system. “Unlike London, Paris or New York, the Tokyo Collection is not organized by one person,” she says. “It’s spread out over a month and there doesn’t seem to be any cohesion to the events. There is no leader, and no-one who is putting up their hand saying they want to be a leader.”

In spite of the Tokyo Collection’s poor reputation, however, Limi realizes she needs to do the donkeywork in Japan before attempting to break into the cut-throat international market. “‘LIMI feu’ has been operational for five years, but I don’t think I have succeeded in Japan yet,” she says. “Brands that don’t succeed in Japan never succeed in other countries. Business is tough overseas so I want to ensure that ‘LIMI feu’ is a lot more established in Japan before looking abroad. At present, I don’t have any plans.

In fact Limi keeps her feet firmly on terra firma when it comes to drafting her short- and long-term goals. She is realistic about the number of sales she is likely to make in Japan from any given collection and hates the thought of people buying her clothes because of her name. “I don’t want everyone to buy my designs,” she says. “It would be boring if everyone liked my designs. Fashion would be the same everywhere and I don’t want that. I will be happy only if people come and try on the clothes they like.”

Indeed Limi is particularly harsh on Japanese consumers she deems “too lazy to think for themselves.”

“People should think more about the products they’re buying,” she says. “They should pay more attention to quality and not simply copy someone else’s style. You are the best person to determine your style because you know yourself best. So what works for one person will not work for another. In a recent interview with Time, I noted that many Japanese people shop at places like Chanel and Yves Saint Laurent but they only buy their bags and accessories; they almost never buy their clothes. They don’t seem to realize that these labels became famous because of their clothes. Japan has a number of excellent fabric manufacturers who each deserve recognition in their own right. Just look at the craftsmen down in Okayama. It seems, though, that Japanese people are more interested in choosing a bag with a famous brand name on it than they are in learning more about the skills of Japanese craftsmen. I wonder how they can act so indifferent towards their own culture?”

One of the biggest challenges Limi has faced in the past few years is motherhood. She has two children, aged two and one, and finds that managing her time has become a lot more difficult. “I have no free time to myself,” she says. “I think looking after children is as difficult as working, perhaps harder, because you are responsible for raising a human being. There have been a spate of natural disasters and terrorist attacks recently. When I was single, such events were always someone else’s problems. But now that I have children, I worry that Japan’s future is not looking so promising. We, as parents, have a collective responsibility for ensuring their future is bright.”

While being a mother is demanding and time-consuming, Limi believes that parenthood has brought a sense of balance to her life that was perhaps lacking when she was younger. “When I had lots of free time, I was always thinking of work,” she says. “I was always going over work-related material, even when I had a day off. Now I think of my children first.”

And, at least for now, she does not believe that having children has significantly altered the appearance of her work. “I don’t think my designs have changed because of my children,” she says. “People grow a little more with each and every day. I do try to reflect this emotional development in my clothing lines, but the trend (for want of a better word) is 100 percent natural. It’s not a conscious decision.”

And so with Limi Yamamoto and the next generation of local designers working hard to win the same plaudits overseas as their forefathers before them, one has to ask whether she would like to see her own children involved in the fashion industry at some point in future. “I’m not sure,” she says with a smile. “If they tell me they would like to get involved I will certainly encourage them. However, I spoke to my father about this a few days ago and we both reached the same conclusion – for now, we think it’s enough. Our bloodline should stop here.”

Story by Elliott Samuels

From J SELECT Magazine, September 2006

Recent Comments