“The neat, tremendous garden of Japan”

These Horned Islands, James Kirkup

Having a theme while you travel always adds texture and depth to a journey. In the case of Japan, there are various options. You could, for example, base your trip around the peregrinations of the country’s more serendipitous writers, like Fumiko Hayashi, Ihara Saikaku, or the great hermit monk Ryokan. Modern architecture might take you to the Global Tower in Beppu, the Miho Art Museum in Shiga, or designer’s Team Zoo extraordinary Nago City Hall in Okinawa.

One of the most enriching themes to follow in this manner is the Japanese stroll garden. Spacious and green, they are usually located in areas that became cities at a later stage, making them easily accessible. The Japanese stroll garden, which achieved its finest form during the Edo period (1603-1867), is the closest existing form to the much earlier Heian period garden.

Built on spacious estates, the basis for these gardens was primarily the leisured lifestyle of the nobles and daimyo (the lords of the capital and provinces), an inherited interest in garden design, and an interest at the time in traveling to view Japan’s natural sights and places associated with literature and myth. The modern Japanese term for these gardens, kayushiki teien (stroll or excursion gardens), hints at the function of large landscapes in which guests were invited to take a leisurely meander through a number of scenes that would be akin to an excursion.

Built on spacious estates, the basis for these gardens was primarily the leisured lifestyle of the nobles and daimyo (the lords of the capital and provinces), an inherited interest in garden design, and an interest at the time in traveling to view Japan’s natural sights and places associated with literature and myth. The modern Japanese term for these gardens, kayushiki teien (stroll or excursion gardens), hints at the function of large landscapes in which guests were invited to take a leisurely meander through a number of scenes that would be akin to an excursion.

As visitors strolled along carefully planned paths, scenes would be revealed, obscured, and then presented from different angles, creating a delightful, entertaining effect. If the gardens were used to entertain guests, they also existed to impress them with the wealth and good taste of their owners.

Tokyo is a good place to embark on a journey of these spacious landscapes. Several of these Edo period landscapes, such as Hama Rikyu, the Kyu Shiba Onshi garden, and the Koishikawa Korakuen still exist in Tokyo today, though in much reduced form. The world of oriental literature and mythology is strongly felt at Rikugi-en, the intriguingly named “Garden of the Six Principals of Poetry”, in the northwest district of Komagome. Feudal lords, aristocrats and wealthy merchants of the Edo period amused themselves constructing large, ambitiously conceived gardens. Highly representational, the best of these landscapes ingeniously mirror concepts and settings, both real and imaginary, found in Chinese and Japanese history and literature, and in actual geographical locations.

A classic stroll garden, construction of Rikugi-en began in 1695 under the supervision of Yoshiyasu Yanagisawa, a highly regarded art connoisseur, literati, and keen horticulturist who served as chamberlain to the Shogun Tsunayoshi Tokugawa. The garden took seven years to complete. In the manner of the stroll garden, it was designed for guests to follow paths that would reveal new and surprising perspectives on hills, teahouses, ponds, and islands planted with pine. Classified as a kaiyushiki tsukiyama sansui teien (a stroll garden with an artificial mountain), the design used the shukkei technique of recreating scenic places in miniature, a popular Edo period garden method.

Traveling west, Kyoto has some two hundred listed gardens, many of which, like the Heien Shrine garden, Murin-an, and the Shugakuin Imperial Villa, combine elements of the stroll garden, but are essentially, composite villa-style landscapes. The diversity of Japanese garden types in the old capital defies simple classification and is a subject I will return to in a more dedicated form at some later stage in this magazine.

Continuing on a westerly trajectory, inevitably takes the stroll garden devotee to Okayama City and Korakuen. Among the garden’s cleverly contrived effects is an artificial thicket, whose miniature valleys, mountains and waterfalls are said to be modeled after scenery along the ancient Kiso Road. Okayama Castle, just beyond the perimeters of the garden, forms part of its “borrowed view,” a concept sometimes applied in Japanese gardens. Used as an optical effect to expand space and create deeper perspective, a garden design may requisition features outside its borders, such as a range of mountains, row of trees, or the outline of a temple roof, to create this illusion.

From Okayama, it is possible to make a daytrip to Takamatsu City on Shikoku Island, to view the magnificent Ritsurin Park, a major garden completed in 1745. Many of the highly distinctive pine trees in Ritsurin Park are designed in a style called “byobumatsu”, a name that comes from the folding screens known as “byobu”. Broad, with horizontally interconnected branches, the effect is similar in density to a hedge, resembling therefore, something akin to topiary.

From Okayama, it is possible to make a daytrip to Takamatsu City on Shikoku Island, to view the magnificent Ritsurin Park, a major garden completed in 1745. Many of the highly distinctive pine trees in Ritsurin Park are designed in a style called “byobumatsu”, a name that comes from the folding screens known as “byobu”. Broad, with horizontally interconnected branches, the effect is similar in density to a hedge, resembling therefore, something akin to topiary.

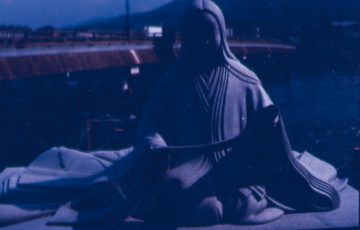

The twin characteristics of refinement and playfulness are perfectly embodied at Suizen-ji-koen, a classic stroll garden in Kumamoto on Kyushu Island. Suizen-ji Park was laid out by the Hosokawa family in 1632 to serve as the grounds for a detached villa. Suizenji, with a central spring-fed pond, is a classic Japanese stroll garden. Its representational features include scenes in miniature from the 53 stages of the old Tokaido highway, the outline of Lake Biwa near Kyoto, and a grass covered Mount Fuji. The photographer Herbert G. Ponting visited the garden in the late Meiji era, recalling in his 1911 chronicle, In Lotus-Land Japan, how he enjoyed a cone of shaved ice and fruit syrup there under a pine tree in August, an especially humid month. Ponting noted groups of adult men bathing in the central pond, and small children “paddling in the water and scampering over the grasses.” It seems that in the Japanese stroll garden, despite their aesthetic credentials, you are also allowed to enjoy yourself.

The sultry climate of the Iso-teien garden in the southern city of Kagoshima, is known for its semitropical plants growing alongside plum and bamboo groves, but also for its celebrated stone lanterns, which add a distinctive visual touch to an already impressive stroll garden. The Shimazu family built a detached villa here with a view of the bay and Sakurajima. The main residence was constructed by the 19th Lord Shimizu Mitsuhisa in 1658.

A highly distinctive visual aspect of the Iso-teien is its stone lanterns. The famous Lion Stone Lantern is on the right of the entrance to the inner garden. This huge piece was designed by Oda Kisanji, after being commissioned by the 29th Lord Tadayoshi in 1884. The sculpted lion and circle stone were translocated from the great stone lantern of Kekura-Ochaya garden, while the copingstones are natural. Improbably, the distinctive Crane-Shaped Stone Lantern served as the first gas lamp in Japan, an odd credential made much of in the garden’s tourist information blurb.

Though much visited, the stroll gardens of Japan are still ideal places to sit quietly with a book of poems, or to contemplate these masterpieces of stone, topiary and water, while sipping from a bowl of fragrant, green tea.

TRAVEL INFO

Because cities have tended to grow around these centers of culture, all of the gardens mentioned in this article are situated within a short walk or bus ride from train stations and subways. Beside healthy bowls of powdered green tea and a Japanese tea ceremony sweet, teahouses usually provide the best view of a garden. Entrance fees to stroll gardens range from ¥400-600. Most have English language brochures. Some, like Tokyo’s Rikugi-en, even have information printed in French and Chinese. Alison Main & Newell Platten’s ‘The Lure of the Japanese Garden’ (Wakefield Press), provides an extensive listing of gardens throughout Japan, with comments and photos.

By Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, October 2010

Recent Comments