“He was obliged to move to Uji where fortunately he still possessed a small estate… after a time he began once more to take an interest in flowers and autumn woods, and would even spend hour after hour simply watching the river flow.”

“He was obliged to move to Uji where fortunately he still possessed a small estate… after a time he began once more to take an interest in flowers and autumn woods, and would even spend hour after hour simply watching the river flow.”

‑The Tale of the Genji, Murasaki Shikibu

For members of the Heian period imperial court in Kyoto, Uji, now reached in just 30 minutes by rail, must have felt a world away. A popular country retreat for aristocrats, elegant retirement estates and dream-like gardens were built here. From their well-situated villas, the nobility could enjoy watching the gentle range of green hills that stand as a backdrop to the majestic Uji River, the home even now of herons and sweetfish.

In the 100th century Fujiwara Michinaga, the emperor’s chief advisor, built a home here, whose gardens and pavilions were further

developed by his son, Yorimichi. Though most of these buildings have long gone, the atmosphere of the site can be felt reading the final sections of Murasaki Shikibu’s masterpiece, The Tale of the Genji. The last sections of the novel in fact, are called the ‘Uji Chapters.’

Some years after Shikibu’s work was completed, Yorimichi decided to convert his villa into a temple dedicated to Amida, the Buddha of the Western Paradise. The centerpiece of the project was the Amida Hall, now known as the Phoenix Hall. Amazingly, the building has survived centuries of weather, fire, earthquakes and neglect. In December 1994 it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Although the hall is currently closed for refurbishment, impressive views of the perfectly balanced main building and its ornamental wings, seemingly floating on the surface of the water, can be had from across the pond that surrounds the complex. Some visitors I met from Texas were excitedly comparing the real Byodo-in with its image as it appears on the reverse side of the Japanese ¥10 coin.

When the doors to the hall are open, a gilded statue of Amida, floating on a bed of lotuses, is visible within. Lotuses, the symbol of Buddhism, are planted throughout the gardens at Byodo-in, their purple and white flowers at their best on an early summer morning.

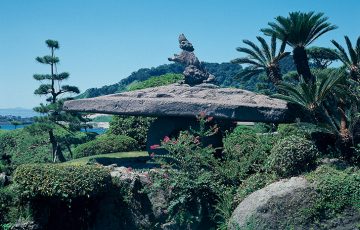

As the only extant piece of architecture form the Heian period, Byodo-in is our most tangible model for reconstructing an image of what Heian court life might have been like. The nobility lived in so-called shinden style residences. Although none of these homes have survived, period paintings suggest that they were very similar in design to the layout of the Byodo-in, making the heritage value of the temple a double blessing. Shinden residences conceived in the Chinese symmetrical style, influenced the use of space in the Japanese gardens of this period. In order to delineate space, to compress macro-concepts and landscapes into the confines of theirrelatively small estates, a compression or miniaturization was sought. A little south of the shinden, a courtyard called the nantei was layered with sand. Although this served as a functional space for garden events like archery, cockfights and poetry readings, the sand performed aesthetic and spiritual ends.

A number of key aesthetics associated with the refinement of the Heian court and it’s co-opting of later Buddhist concepts were added to the process and appreciation of garden design at this time. Elevating these stone tableaus from the merely pictorial or sculptural were a host of superimposed and applied concepts, in which Nature was not simply controlled and remodeled, but modified and elevated to reflect the more subtle influences of Taoism, Buddhism, as well as Japanese aesthetics. Gardens in the Heian period were expected, like the court itself, to radiate miyabi (grace and refinement), an aesthetic principal that applied as much to garden tastes as it did to personal deportment, court protocol, a knowledge of poetry and clothing.

Mujo (impermanence and evanescence), stemming from the first of the three laws, shogyo mujo, declared that “all realms of being are temporary.” The indeterminate nature of gravel and sand, materials that require constant maintenance to preserve the patterns raked so ephemerally across their surfaces, readily suggests the Buddhist notion of impermanence, sometimes referred to as the ukiyo, or “floating world.”

Consciously applied aesthetics of this kind were tempered by a more lugubrious aspect to the culture deriving from the third of the Three Laws of Buddhism: the belief that 2,000 years after the death of the historical Buddha, the world would enter into a period known as mappo, the “end of law.” This was said to foretell and witness a degeneration of moral and religious mores, one that would likely lead to social chaos.

As this era was believed to begin in 1052, it is little wonder that a sense of fatalism and gloom hung over the Heian court at this time, something that translated into other concepts, inevitably seeping into literature, the arts and gardening. Byodo-in was opened in the first year of mappo.

As this era was believed to begin in 1052, it is little wonder that a sense of fatalism and gloom hung over the Heian court at this time, something that translated into other concepts, inevitably seeping into literature, the arts and gardening. Byodo-in was opened in the first year of mappo.

A heightened awareness of life prefiguring its own demise might be construed as a morbid tendency, but to the Heien courtiers and those within their immediate sphere of influence, such emotional responses were evidence of a sensitivity to the impermanence of nature, the very beauty and pathos of life. While other religious societies in Asia may have understood this on a metaphysical level, Heian courtiers interpreted such concepts literally. Arson, robbery and the ambitions of warrior-priests, all prevalent at this time, seemed to confirm the prophecy.

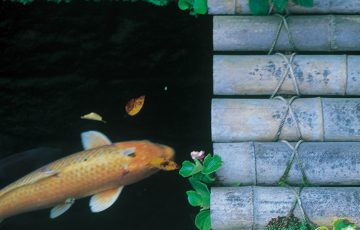

Besides Byodo-in and its evocations of Heian, Uji has several other features of interest, not least of which is the river itself and its series of bridges, islands, shrines and the teahouses that line its banks. The journey into Uji’s past begins at the ‘Bridge of Floating Dreams,’ the modern version of the original 7th century structure that spans the river. A narrow shopping street runs from here to Byodo-in. The first thing you will recognize here is the smell of roasting tea. Fragrant uji-cha was first planted in the 13th century. Uji green tea is now regarded as the finest in Japan. On summer evenings, demonstrations of cormorant fishing take place along the river, adding to the magic of fireworks, poetry readings and other events.

It is here in the older section of town along the river, that the spirit of Murasaki Shikibu’s Uji, a resting place for the heart and mind, can be most strongly sensed. Now, thanks to its World Heritage status, it can be shared with the rest of the world.

TRAVEL INFORMATION

Uji can be reached on the JR Nara line from Kyoto and Nara. The journey takes 30-40 minutes. The tourist office along the river near Byodo-in has maps and other useful data in English. Most visitors base themselves in either Kyoto or Nara, visiting Uji as a day trip. If you would like to stay in Uji, rooms can be checked out through the office at 0774-23-3334. Magozaemon, opposite the entrance to Byodo-in, is excellent for homemade noodles and green tea udon dishes. Taiho-an, a traditional teahouse next to the information office, offers bowls of exquisite green tea. If you are in Uji during the summer months, check out displays of cormorant fishing along the river.

Story & photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, April 2008

Recent Comments