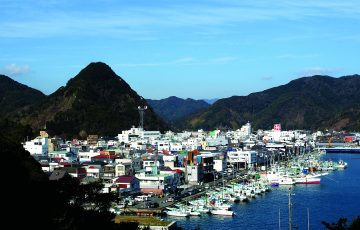

Kohama, a small island of just 436 inhabitants at last count, follows the classic small island layout of the Yaeyamas: a functional, largely uninhabited port, a circular road, and a village located smack-bang in the middle of the island – a sensible precaution against typhoons and inundations. Kohama village is a classic study in small island design. While there are one or two concrete homes and minshuku, the houses here are mostly traditional, one-story residences in varying states of disrepair, speaking to the fact that Okinawa is not a rich prefecture.

Kohama, a small island of just 436 inhabitants at last count, follows the classic small island layout of the Yaeyamas: a functional, largely uninhabited port, a circular road, and a village located smack-bang in the middle of the island – a sensible precaution against typhoons and inundations. Kohama village is a classic study in small island design. While there are one or two concrete homes and minshuku, the houses here are mostly traditional, one-story residences in varying states of disrepair, speaking to the fact that Okinawa is not a rich prefecture.

Kohama is situated in the clear blue waters between Ishigaki Island and Iriomote Island. This is the “Yonara waterway,” a famous place for spotting giant Manta. With a circumference of just 16.6km, it’s possible to circle the island by scooter or bicycle, if you start early. The island and its watery parameters have been designated as part of the Iriomote National Park, affording it a degree of environmental protection it might not have otherwise enjoyed.

Like other tiny islands that pepper the aqua blue waters of the Yaeyama chain in southern Okinawa, there isn’t a great deal to actually do on Kohama-jima. But for visitors who appreciate the nature, detail, atmosphere, and minutiae of life in these distant parts, there is much to recommend on this island.

As attractive as Kohama village is, it doesn’t have the manicured beauty of other island settlements in this group like Taketomi-jima. This is a working island, revolving around the daily life of people engaged in agriculture and fishing. Perhaps because of these simple but painstaking activities, they seem a friendly, largely unspoiled breed, communal in a way that has mostly vanished elsewhere. Youngsters on their vacations help out parents and grandparents in shops, small businesses like bicycle rentals, or in the fields; everyone has time for a cordial greeting or chat with neighbors.

Kohama receives a modest number of visitors, but is otherwise blissfully quiet. Six passengers alighted from the ferry I took to the island. Two of them were locals. Like many of these islands, Kohama supports a small population. 615 people live here, with about 50 children attending the combined Junior and Senior High school, a magnificently appointed building from which you can admire the peerless blue waters below. Resident numbers on Kohama may sound low, but compared to some of the smaller islands in the chain, this place is positively bulging. Nearby Panari Island supports a mere seven inhabitants.

Although a stay on the island is recommended, a circuit of its modest features can easily be made on a day trip. The port area was originally a fishing village, home to families who settled there after leaving the mainland Okinawan town of Itoman. South of the port, Tumaru Beach is where many visitors head on arrival, but a little further on takes you to a more secluded possibility, Kubazaki, a white sand beach known to a cognoscenti of visitors who go there to collect shells. Ufudaki, the island’s 99-meter “mountain,” can be a surprisingly stiff climb, especially in the summer. One local belief maintains that gods moved the peak from Taketomi-jima, which would certainly explain why that island is so flat. The views at the top, taking in the islands of Iriomote, Kuro, Hateruma and Aragusku, are impressive enough to be celebrated in a folk song called “Kohama Bushi.” Japanese people will also know the name of the island from a shamelessly sentimental NHK TV show from a few years back called “Chura-san,” which was filmed here.

Kayama, or “Rabbit Island,” is clearly visible from the observation peak. A ten-minute boat ride will get you to this island where thousands of white rabbits live, and where the snorkeling is said to be superb. Its shore is the best spot to glimpse the sandy “Phantom Island.” The islet appears only at low tide, hopefully not a foretaste of climate change and rising seas. Taketomi-jima, also within this circle of enchanted islands, is both flat and low-lying, a worrying augury for the future.

Kayama, or “Rabbit Island,” is clearly visible from the observation peak. A ten-minute boat ride will get you to this island where thousands of white rabbits live, and where the snorkeling is said to be superb. Its shore is the best spot to glimpse the sandy “Phantom Island.” The islet appears only at low tide, hopefully not a foretaste of climate change and rising seas. Taketomi-jima, also within this circle of enchanted islands, is both flat and low-lying, a worrying augury for the future.

Rice has been cultivated here for centuries, but the island’s most conspicuous crop is sugarcane. Sugar is second only to tourism as an essential part of the island’s economy. Reflecting the very different climatic and horticultural conditions of these sub-tropical islands, most of the sugarcane is harvested from December. As with many of these small islands in the Yaeyamas, sugarcane is still cut by hand. With such a small population, extra hands are recruited from the mainland to work in the fields. Kohama Island Farm has its very own volunteer program called the “Sugar Cane Harvesting Experience.” Helpers, who receive no pay but are given full board and three square meals a day, typically work from one to three months cutting the cane, which towers above the heads of the workers. Kohama’s “Sugar Road” passes into open fields, where cane grows high on both sides, but once the stands are cut the road reverts to being just another island route.

The mangrove forests along the island’s west coast are another sight visible all year round. A small path leads through a wood to the curving bay where these well-preserved plants take root. While the cement wall and graduated observation decks are unsightly, the views, access, and utility they offer are welcome. This would be a superb place to loiter at sunset, watching the mangrove darkening to pink and purple against the red sheet of water, but these islands are infested with poisonous snakes. I only saw one example of Kohama’s indigenous “hundred-meter snake,” giving it a respectful berth before moving on. The name refers not to its size, but to local lore that holds that, if bitten, that will be as far as you get before breathing your last breath.

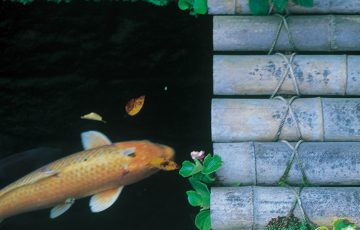

Ultimately, it is the village itself, with its friendly inhabitants and gentle hum of activity that draws back the visitor. Nature and local materials have infiltrated the small homes and gardens here. Each home is surrounded by a coral wall. Some of the older gardens have a second inner wall, in the manner of Chinese screens intended to deflect or prevent evil spirits from entering the house. They also serve as windbreaks and ensure privacy. The outer walls are not the geometric, rectilinear design components they are in Japanese gardens, doing service instead as shelves for flowers and plants like aspidistra and creepers, even doubling as trellises for vegetables like marrow. Trellises of bitter melon blend with papaya, banana, fig, and mango trees. Signs of old wells, water storage jars, old wooden tables, and planters create the impression of a messy but used space.

The garden’s decorative touches reflect climatic differences, but also disparities in taste and cultural preference: wind chimes, seashells, and Okinawan shisha lion figures adorn roofs and garden entrances. A fondness for displaying the sharp, spiny coral rocks shows a Chinese predilection for craggy, pockmarked stones. Arguably, the first designs were coral gardens influenced by living on small islands surrounded by marine gardens.

The garden’s decorative touches reflect climatic differences, but also disparities in taste and cultural preference: wind chimes, seashells, and Okinawan shisha lion figures adorn roofs and garden entrances. A fondness for displaying the sharp, spiny coral rocks shows a Chinese predilection for craggy, pockmarked stones. Arguably, the first designs were coral gardens influenced by living on small islands surrounded by marine gardens.

Unlike mainland Japanese gardens, which often seem like art arrangements intended for hushed observation, Okinawan gardens are thoroughly lived in. Less places to contemplate nature than to make contact with it, locals sit and chat under the shade of trees, smelling nature, feeling it ripple over their skin. And the sense of color too, is invariably different: sandy ground, luxuriant tropical flowers, the light tones of worn, salt-encrusted wood verandahs, eaves, and pillars, and orange roof tiles against clean blue skies form the palette here.

If you decide to stay in a minshuku – the best way to absorb the air of the island – you will likely spend time in their gardens, which, like the island itself, are small sanctuaries of peace. Linger in these marine gardens long enough, and you have a good chance of experiencing something like an Okinawan trance state.

Story and pictures by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, March 2010

Recent Comments