You could quite easily plan a travel itinerary around Japan by plotting the location of its teahouses. Where there is culture, you might say, there is tea.

You could quite easily plan a travel itinerary around Japan by plotting the location of its teahouses. Where there is culture, you might say, there is tea.

Eclipsed by the grandeur of mountains, even the most hubristic will feel humbled. It’s something similar to the willing, shrinking of the ego that takes place when we enter the roji, or Japanese tea garden. Not just a walk through a physical space; our steps through the tea garden are also a walk through time.

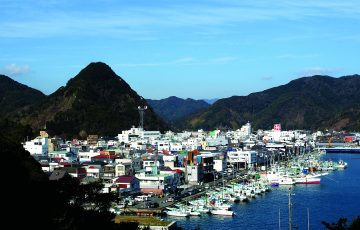

The serious business of drinking tea has an august history in Japan. Tea leaves were introduced into the country in the 12th century by the pioneer Eisai. Tea as a sophisticated pursuit entered Japan in the Muromachi period (1334-1568) from Ming China. The gateway for trade at this time was the port city of Osaka, and the rich merchants of its Sakai district became notorious for the sumptuous amounts of money they were prepared to pay for tea implements, particularly ceramic ware.

The interest in tea gained momentum in the next century with the teacher Muso Kokushi, through the efforts of the calligrapher, poet and abbot of Daitoku-ji temple, Ikkyu Sojun, and with the contribution of the 16th century master, Takeno Joo. Ikkyu, one of the most creative and original artists and thinkers of his day, suggested the idea that tea and Zen Buddhism could be combined.

The interest in tea gained momentum in the next century with the teacher Muso Kokushi, through the efforts of the calligrapher, poet and abbot of Daitoku-ji temple, Ikkyu Sojun, and with the contribution of the 16th century master, Takeno Joo. Ikkyu, one of the most creative and original artists and thinkers of his day, suggested the idea that tea and Zen Buddhism could be combined.

Murata Juko is generally credited with raising the tea ceremony to an art form, creating a separate environment away from private residences and temples in the form of the sukiya, or teahouse. He also introduced the deliberately restricted but cozy yo-jo-han, or four-and-a-half tatami mat room. This so-called ‘grass-hut style’ of tea ceremony paved the way for a more spiritual approach to tea.

It is the name Sen-no-Rikyu, though, that most people associate with the ultimate refinement of style and elements in the Japanese tea ceremony. Rikyu raised the level of the ceremony to such a degree that a cultured pastime became the ‘Way of Truth.’ In an object lesson in not mixing politics and aesthetics, Rikyu’s relations with the generalissimo Toyotomi Hideyoshi would prove disastrous. An admirer of Rikyu, Hideyoshi exploited the locations of teahouses as venues for secret political meetings, something that must have deeply unsettled the tea master.

Although the reasons remain unexplained, it seems that Rikyu’s position, his authority and status, somehow represented a slight to the general, prompting him to order the master to commit seppuku (ritual disembowelment). With typical resignation, and a touch of bravura, Rikyu’s death poem reads:Seventy years of life -Ha ha! And what a fuss!With this sacred sword of mine,Both Buddhas and Patriarchs I kill!

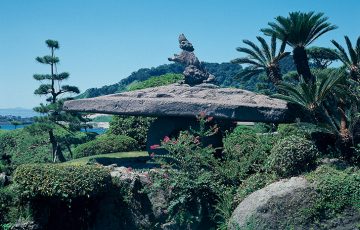

Rikyu’s disciple, Furuta Oribe, is generally credited with creating the kind of garden design we see today. Oribe, who felt that tea gardens were overly rustic, introduced the idea of placing stones and trees in gardens, creating a greener and more aesthetically pleasing – albeit more contrived – tea environment. Oribe had the garden divided into sections by using bamboo and thatch fences, wooden gates, paths and stepping-stones. Stone lanterns were added to the mix for atmosphere, and the particularly weathered specimens were much prized. Stone stupas and Buddhist statuary were also used as occasional features, along with reused objects such as discarded granite bridge piers and millstones. Old temple roof tiles were sometimes sunk into the earth to create borders.

Rikyu’s disciple, Furuta Oribe, is generally credited with creating the kind of garden design we see today. Oribe, who felt that tea gardens were overly rustic, introduced the idea of placing stones and trees in gardens, creating a greener and more aesthetically pleasing – albeit more contrived – tea environment. Oribe had the garden divided into sections by using bamboo and thatch fences, wooden gates, paths and stepping-stones. Stone lanterns were added to the mix for atmosphere, and the particularly weathered specimens were much prized. Stone stupas and Buddhist statuary were also used as occasional features, along with reused objects such as discarded granite bridge piers and millstones. Old temple roof tiles were sometimes sunk into the earth to create borders.

The ground at many tea gardens is covered in moss. This is particularly true in Kyoto, where the humid summers are perfect for this, but I have seen moss growing well at places such as the New Nezu Museum garden in Tokyo’s Minami-Aoyama district, where the tree cover protects it from direct sunlight, and at the cluster of teahouses in Rikugi-en in Komagome.

Such gardens do not reflect Nature – they arrange it, and in the most accomplished cases, transcend it. The visitor enters not just a garden, but a world of metaphor. By definition, tea gardens and teahouses are best suited to secluded spots, a condition that is becoming more difficult to satisfy as cities expand to the fringes of tea grounds. The teahouse in the Kyu Furukawa Garden in Komagome is a good example of this intrusion. An exquisite building located beneath the tree cover of a wooded section of the garden, its position close to the perimeter of the garden and a busy road jammed with traffic, means that it is almost impossible to sit in contemplative silence.

Cha-no-yu (or Sado, the tea ceremony), like yoga or Zen meditation, requires the senses to be relaxed, but alert and receptive. Without thephysical rigors of yoga and zazen, the Way of Tea demands only one thing: humility. The tea ceremony condenses aspects of Japanese aesthetics, history, art, culture and heritage into a ritual of symbolic beauty, but also therapeutic benefit.

In an imperfect world, Japanese gardens represent an idealized environment; the world as it should be, all the right balances and dynamics firmly in place, nourishing the mind. The immediate beauty and freshness of the Japanese garden, seamlessly blending nature and art, can only be fully revealed when such elements, concepts and the representations that embody them are understood. While its symbolic intentions are not hidden, you have to know the garden lexicon to read them. The principal elements required in the world of tea are kei (reverence), jaku (tranquility), sei (purity), and wa (harmony). Should one of these be absent, the overall spiritual and artistic integrity will be jeopardized. All these components are represented symbolically in the environs of the teahouse.

The traditional teahouse should have a rustic character. Garden writer and designer Marc P. Keane has written of these gardens, “To walk the length of a roji is the spiritual complement of a journey from town to the deep recesses of a mountain where stands a hermit’s hut.” The sense of worn antiquity is transmitted not only in the materials that compose the teahouse itself, but in the tea utensils, particularly the ceramic bowls used in Sado.

In tea gardens there is a strong sense of antiquity and decay, even in relatively young ones. This is perceived as a maturing of the garden, an enhancement rather than a spoiling or erosion. This mood is especially sensed during the humid summer months, when the beauties of erosion are seen more vividly in the surfaces of mottled and streaked rocks, stone lanterns, and water-basins covered in moss and lichen, and in the discoloration of walls.

A subdued mellowing (the result of exposure to wind, rain, and humidity), can take a long time to develop. The result is a much cherished aesthetic called wabi-sabi. The etymology of the expression is revealing, wabi stemming from wabishi (lonely, wretched); sabi from sabiru (to age and mature), and sabishi (lonely, inconsolable). The compound suggests a desolate beauty transformed by weathering, the resulting patina of age creating an object or scene of exquisite refinement and taste.

Its emphasis on hospitality encourages a generosity of spirit, and like the simple act of sharing a pot of tea at home or in a café, it represents a coming together, a uniting of friends, family, or community. Admittance to the tea garden, passage through it to the teahouse, and the stages of the tea ceremony may be liberating, but the rules are strictly delineated, every gesture controlled and meditated. The guest’s passage into the teahouse is worth recounting as it evokes many of the aesthetic values connected to the ceremony.

The garden is usually divided into two sections: the soto roji (outer garden) and the uchi roji (inner garden). A guest will first be led to a bench called the koshikake, where they will await a call from the host. Once summoned, you proceed towards the naka kuguri (middle gate), where the host may – in a more formal version of the tea ceremony – greet you. The middle gate is an attractive feature in its own right, covered in either cypress bark or in thatch. It is necessary to slightly stoop as you pass through the gate, the deliberate low height intended to instill humility. The path through the inner garden will be across stepping-stones, whose carefully selected height and distance from each other is done to make the walk more interesting, but also to slow down the guest, to create a fitting pace for the event to come. Guests are now ready to purify themselves with ablutions performed at the chozubachi, or water basin. Again, it is necessary to crouch down for this act, which involves washing the hands and mouth with the use of a bamboo ladle called a tsukubai bishaku. Guests will now be ready to enter the teahouse, the sukiya itself.

There is no place for anxiety or neurosis in the teahouse. Once seated before the tea utensils, we are able finally to slough off the real and metaphorical grime of our everyday lives, if only temporarily. We return from the tearoom enriched, cleansed.

Story and pictures by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, February 2010

Recent Comments