In his early teens, Kaido Hoovelson played basketball. Like many other kids in his village in Estonia, he would have grown up watching the great Michael Jordan strut his stuff with the Chicago Bulls.

In his early teens, Kaido Hoovelson played basketball. Like many other kids in his village in Estonia, he would have grown up watching the great Michael Jordan strut his stuff with the Chicago Bulls.

By his later teens, his above-average size started to become apparent, and Kaido moved into the world of high school sumo. Asked why he took this step – into a culture so far removed from his own – his never-really-thought-about-it response was perhaps a tad less prophetic than his fans might have hoped for. He did, however reveal a common method of entry into Japan’s quasi-national sport for many overseas hopefuls: judo club. In his school, he explained, “it was the same coach” for judo and sumo.

After graduating from high school, Hoovelson worked as a nightclub bouncer, a fact the Japanese media were keen to point out after he first entered Ozumo. Reports of at least one life-threatening experience surfaced when Baruto was interviewed as a rikishi. He later agreed his experiences had been exaggerated, adding, “But bad things [did] happen.”

Given the chance to move to Japan to enter the world of professional sumo, initially by an official representing the Kagoshima Prefecture Sumo Association (KPSA), Hoovelson was accepted into the famed Mihogaseki-Beya led by former ozeki Masuiyama. This was the only stable (heya) at the time willing to accept a foreign national. When offered this opportunity by the KPSA rep, in his signature succinct style, he apparently answered “Why not?”

Not long after his first few training sessions, he entered the July, 2004 Grand Sumo Tournament in Nagoya ranked in the lowest Jonokuchi Division. He adopted the ring name “Baruto” in honor of the Baltic Sea, flanking his native Estonia. Scheduled to fight seven times over fifteen days, the boy from the Baltic – then still a teen – beat every man sent into the ring with him, employing six of sumo’s official 80-plus finishing techniques along the way. Thus crowned Jonokuchi champion, he saw promotion to the Jonidan ranks follow. There, in the autumn of the same year, he dispatched another seven foes before winning an all Mihogaseki Beya play-off against his much smaller heya-mate Satoyama Kosaku.

The domestic and even international media were now waking up to the possibility of a blonde boy from northern Europe rising to the top of the sumo ranking system of six divisions in record time.

The domestic and even international media were now waking up to the possibility of a blonde boy from northern Europe rising to the top of the sumo ranking system of six divisions in record time.

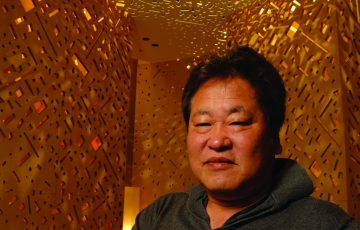

The pressure was on, but Baruto, as he was now commonly known, was still bewildered at his new surroundings in Japan. Asked several months after his first championship victories his impressions of his new home in Tokyo, he answered, “So big is Tokyo! So much people and cars, and so small streets” – with a grin lighting up his face. This grin, now seen on T-shirts sold at Ryogoku Kokugikan, is presumably his most endearing factor to the many fans wearing the shirt on any given day of a tourney.

Around this time in his career, he actually did what many never get to do in the world of sumo – he switched stables. As a sport with its roots in thepanese feudal system, sumo wrestlers are expected to join a stable as young men, and for the duration of their careers in the sport, fight out of that stable. Transfers are unheard of – barring as a result of retirement of the stable master, or the decision by a junior master in a given heya to start his own place. When permitted this breakaway, the stable master is usually allowed to take those he himself recruited on behalf of the parent heya, thereby avoiding the need to start from scratch in his new venture.

This affected Baruto in a significant way, as he and six of his Mihogaseki stable mates moved from the Ryogoku heartland of sumo into the relative wilds of Ota-ku in south Tokyo – now as disciples of Onoe Oyakata, former komusubi Hamanoshima. Asked to comment on this move at the time, Baruto appeared a little confused, “How do I feel? I don’t know. Here (gesturing to indicate he meant Mihogaseki-beya) is good. But [the] new place will be good [too].”

His nation’s status as a highly contested land has ensured Baruto’s exposure to several languages. In addition to speaking excellent Japanese, he is proficient in three languages other than his native Estonian. “Russian is my best (after Estonian), then English. German is last.” Despite his talent for picking up languages, the now sekiwake – sumo’s third highest rank – is a man who relishes solitude. His hobby is fishing, “but not in the Sumida River,” he explains, and sensibly so!

Promotion up the ranks followed his earlier successes, and he finally made the salaried Juryo ranks in September 2005. In his debut in the sport’s second division, Baruto finished with an impressive 12-3 record. He entered the following tournament only to be forced to drop out before the action began with appendicitis, missing the basho in its entirety and suffering a demotion back to the unsalaried makushita level for the start of 2006. Back to back Makushita, then (after another promotion) Juryo division championships followed; the latter particularly noteworthy as it saw him win all 15 bouts he had – to end 15-0.

By May 2006, less than two years after his debut in sumo, he was now in the top division and even with a special prize to show for a fantastic 11-4 finish, was incredibly down to earth when asked how he felt waking up the following day – “I feel like every day, nothing special feeling.” Questioned further about the media hype then surrounding him, he came out with a comment most non-Japanese will have uttered at some time, “Japanese media all food, food, food. What do you like, how do you feel?” he said at the time – gesturing and pulling a few faces.

By May 2006, less than two years after his debut in sumo, he was now in the top division and even with a special prize to show for a fantastic 11-4 finish, was incredibly down to earth when asked how he felt waking up the following day – “I feel like every day, nothing special feeling.” Questioned further about the media hype then surrounding him, he came out with a comment most non-Japanese will have uttered at some time, “Japanese media all food, food, food. What do you like, how do you feel?” he said at the time – gesturing and pulling a few faces.

The years following his appearance in the top division have seen this still relatively young man from the Baltic take great strides in Japan’s sport of giants, but at 184kg and 197cm, this is one foreign rikishi more than able to handle himself and mix it up with the reigning Mongolian heavyweights and local wannabes that have so underperformed in recent times.

Late 2008 and 2009 saw him flirt with promotion beyond the sekiwake rank he now holds, to the revered rank of ozeki that so few in the sport ever get near. Impressive double-digit winning records at the end of last year also indicate his ability is increasing at this level, so perhaps it will not be long before there’s an ozeki run by the blond bomber from Estonia.

In heading higher and potentially becoming the second European (after Bulgarian Kotooshu) to attain ozekihood, hopefully this multilingual basketball fan with a ready smile will stay true to his own message to sumo fans when he said, “Life is fun, enjoy it. Enjoy life, enjoy yourself, enjoy other people.”

Story by Mark Buckton

From J SELECT Magazine, February 2010

Recent Comments