For several years after WWII, in the days before New Caledonia and Hawaii became de rigueur and affordable, Beppu, along with Miyazaki to the south, was one of Japan’s most popular and exotic honeymoon spots. Even the exceptionally well-traveled writer Yukio Mishima and his bride Yoko spent part of their honeymoon there. The city is no longer a fashionable resort – though it remains a much-visited one – but it does have a kind of authority among hot springs.

For several years after WWII, in the days before New Caledonia and Hawaii became de rigueur and affordable, Beppu, along with Miyazaki to the south, was one of Japan’s most popular and exotic honeymoon spots. Even the exceptionally well-traveled writer Yukio Mishima and his bride Yoko spent part of their honeymoon there. The city is no longer a fashionable resort – though it remains a much-visited one – but it does have a kind of authority among hot springs.

The intense geothermal activity of the region contrasts with a leisurely atmosphere and pace, typified by the sight of carefree Japanese and foreign tourists strolling around the stree ts in their yukata (light cotton kimonos). Along the dividing line between fire-infused earth and water are intermediary states, promenade hot springs, beachside suna-buro (sand baths), and the bay itself, where hot water bubbles up through seabed fumaroles, creating a small bio-sphere where radiantly colored fish, swimming up from the south, have discovered a warm lagoon. Because of its trade winds, Beppu is relatively cool in summer and warm with their absence in winter. Monkeys, partial to southern climates, are said to swarm in the mountains behind the city, though you would be hard-pressed to see one descend to the ocean, plunge in and catch a plump fish, as locals maintain.

In Beppu, geothermal heat rises from the earth through lush green surfaces that create landscapes of fantastic configurations, steam curling above the friable crust into scalding pools, or gushing with terrifying force from the outside pipes and faucets of its hot spring inns. Beppu is said to have over 3,000 water sources, and a compliment of some 160 or so bathhouses. Even your modest guesthouse will be obliged to offer at least one spring bath. Onsen water is also piped into private houses, where it serves a variety of uses ranging from common bathtub water, providing heat to steam food, and warming up greenhouses where mid-winter muskmelons are cultivated.

If you can accept its gimmickry and brazen commercialism, this glitzy, neon-strung hot spring resort, a mélange of pachinko parlors, love hotels, sleazy bars, night clubs, and hot baths visited by over 12 million tourists a year, constitutes an extraordinary thermal and entertainment roller-coaster. Beppu offers some interesting variations and twists on the simple theme of a hot bath. Visitors can soak in a series of tubs of graded temperatures, plunge into thermal Jacuzzis, or immerse themselves up to the neck in steaming mud. At certain times of the year, bathers soak in water made fragrant by the addition of orange peel or segments of yuzu (Japanese citrus), placed in floating bags.

If you can accept its gimmickry and brazen commercialism, this glitzy, neon-strung hot spring resort, a mélange of pachinko parlors, love hotels, sleazy bars, night clubs, and hot baths visited by over 12 million tourists a year, constitutes an extraordinary thermal and entertainment roller-coaster. Beppu offers some interesting variations and twists on the simple theme of a hot bath. Visitors can soak in a series of tubs of graded temperatures, plunge into thermal Jacuzzis, or immerse themselves up to the neck in steaming mud. At certain times of the year, bathers soak in water made fragrant by the addition of orange peel or segments of yuzu (Japanese citrus), placed in floating bags.

Hot springs being the dominant theme, many of the town’s sights are linked to hot water. The bubbling, burping mud and lethally hot mineral-tinted waters of Beppu’s Nine Hells are the most renowned, and visitors could do no worse than to follow the well-trodden Jigoku-meguri (onsen hell trail). Seven of the nine are found in the old geisha district of Kannawa, each a sight in itself. The names alone are enough to stimulate inquiry. Thus we have Chi-no-Ike Jigoku (Blood Pond Hell), a pool jammed with red clay particles, and Umi Jigoku (Ocean Hell), a perfect South Pacific blue full of vitriol muriated saline. The milky waters of White Pond Hell bulge with natrium chloride, an ingredient that promises relief from diseases affecting the digestive organs, while Bozu Hell has mud bubbles and a boiling surface supposedly resembling the shaven head of a monk.

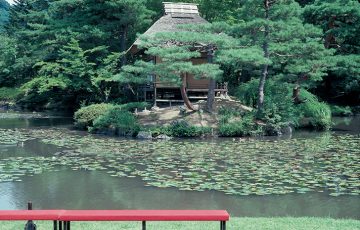

Beppu’s geothermal heat produces other marvels in its extraordinarily lush flora, something noted by the English writer James Kirkup, who wrote in his travelogue ‘These Horned Islands,’ “Kyushu, seahorse on a capering keel….The neat, tremendous garden of Japan.” Its luxuriance of flowers, early blooms, cycads and phoenix palms are all in evidence in Beppu. It’s a wonder that plants can survive at the edges of the fiery pools, but the cycads, bonsai pines, and giant lily pads seem to thrive from the minerals and steam the pits produce. Eggs also do well, and are frequently lowered in baskets into the pool for a rapid hard-boiling, their taste giving off hints of magnesium, radon and sulphur. Souvenir shops, food and snack vendors have staked out spots near all the pools, some more obtrusively than others.

Beppu’s geothermal heat produces other marvels in its extraordinarily lush flora, something noted by the English writer James Kirkup, who wrote in his travelogue ‘These Horned Islands,’ “Kyushu, seahorse on a capering keel….The neat, tremendous garden of Japan.” Its luxuriance of flowers, early blooms, cycads and phoenix palms are all in evidence in Beppu. It’s a wonder that plants can survive at the edges of the fiery pools, but the cycads, bonsai pines, and giant lily pads seem to thrive from the minerals and steam the pits produce. Eggs also do well, and are frequently lowered in baskets into the pool for a rapid hard-boiling, their taste giving off hints of magnesium, radon and sulphur. Souvenir shops, food and snack vendors have staked out spots near all the pools, some more obtrusively than others.

Each pool has its residing demon, ghost story or association with the horrific. Malign spirits are said to be responsible for luring many a gullible or deranged soul over the lip of the boiling cauldrons. More famously, early 17th century Christians, both native and foreign missionaries, were suspended and lowered into the pools in an attempt to make them apostasize. In more recent times, the suicidal have jumped into the mineral broth in the knowledge that, once in, life is irretrievable. What bystander, after all, would dare to strip down and plunge in to rescue a stranger in the face of certain death?

Toads and snakes are also drawn to these waters on account of their warmth. Presiding deities and spirits have been co-opted in the manner of garden ornaments to add interest to the boiling hells. Fudo, the Fire God and guardian of the gates of hell, presides over one pool; a statue of the Wind God, made of perishable wood, humping a bag of air over his shoulder, peers out from behind the chicken wire of a small pavilion; elsewhere, a row of bodhisattvas emerge from clouds of steam. Not all of this is in the best taste: the god Ebisu, cast in weather-proof perspex, greets visitors at the ticket wicket to one complex; in another, steam gushes through the hollowed out nostrils of a concrete Kamado, dragon of the boiling hells, a moment of shameless gimmickry. At Oni-yama Jigoku, live crocodiles and alligators, until recently kept in the warm, growth-accelerating waters before being turned into traveling cases and shoes, add to the commercial savagery of the scene.

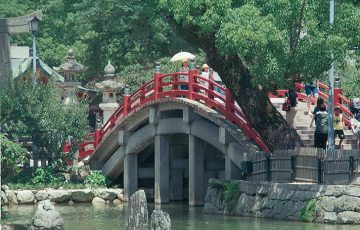

“At resorts of this kind,” as writer John Lowe remarked in his book Into Japan, “some pools are outdoors, some are little more than large and lavish bathrooms, but some are vast indoor pools decked out in all the finery of an Amazonian rain forest.” Modern, sea level hotel onsens compete with hot spring emporiums with jungle baths. More enduring are the Meiji-era bathing establishments located in the back streets of Beppu or, like the Okamotoya Yamanoyu, a traditional inn with a Japanese garden in the Myoban Yu no Sato district, (Far left) Steam rises from inns in the Kannawa district of Beppu; (Below left) Coins thrown for good luck on the lily pads at Umi Jogoku; (Bottom left) Palms along Beppu’s ocean esplanade; (Below) The Beppu Beach Bath waits for customers

Story and photos by Stephen Mansfield

From J SELECT Magazine, July 2010

Recent Comments